CSI: Mars

NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover took this selfie, made up of 62 individual images, on July 23, 2024. A rock nicknamed “Cheyava Falls” — which has features that may bear on the question of whether the red planet was long ago home to microscopic life — is to the left of the rover near the center of the image. Image courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

By Wendee Nicole

Travelling to Mars has loomed large in the public’s imagination since at least the late 1800s when H.G. Wells' “War of the Worlds” tale of a Martian invasion was serialized in print. In 1899, respected scientist Nikola Tesla believed he was receiving transmissions from Mars, which intrigued the science community and the world. For the next several decades, the planet and its potential for extraterrestrials stayed front and center in news, sci-fi films, books and even religious debates.

It wasn’t until 1965 that we first saw up-close photos of Mars taken by Mariner 4 spacecraft flying by the planet, and later by a series of NASA robotic rovers — Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity and Perseverance — that successfully landed on its surface. While we now know Mars is inhospitable to life as we know it, scientists have found clear evidence of once-abundant water, a prerequisite for any known organic life. The search continues on: Perseverance — the most recently landed rover — is gathering up rocks for an eventual return to Earth, possibly revealing signs of organic molecules or even fossilized evidence of past microbial life.

Studying Martian rocks and regolith — dust and other sediments — in laboratories on Earth will provide greater insight into the geologic history of Mars, answering “questions such as how the planet formed and evolved, what its climate was like in the past, the history of water on the planet, and of course, was there ever life on Mars?” posits Meenakshi (Mini) Wadhwa, a planetary science professor at ASU. “All of the big questions that humanity has pondered ever since we were able to see Mars through a telescope,” added Wadhwa, also the director of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Since landing on Mars in February 2021, the roving robotic geologist has sealed 29 sample tubes, including 23 rock cores, two regolith samples, one atmospheric sample and three “witness samples” while rocking and rolling over more than 22 miles (35 km) of the planet’s uneven terrain, gathering samples as it goes. Most recently, it climbed to the rim of Jezero Crater, ascending more than 1,600 vertical feet over a three-and-a-half-month period, and has begun the next science campaign at the crater rim.

As you can imagine, determining the best areas to sample from millions of miles away takes skill and precision.

“Imagine if you said, ‘I want you to go understand planet Earth, and you can only collect 38 samples,’” says Jim Bell, a planetary science professor at ASU. “You really have to be smart about it — getting the lay of the land, understanding the geology, the topography, the chemistry, the mineralogy. These are things that we are directly impacting with our operations team at ASU, and our science team at ASU and other universities and institutions around the world.”

Bell currently serves as principal investigator for Mastcam-Z — a multispectral, stereoscopic imaging instrument on the Perseverance rover — designed, developed, tested and operated largely from ASU’s Tempe campus, with help from Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego.

Perched on the mast, Mastcam-Z "sees" in red, blue and green, as well as in the ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths. Unlike its predecessor, Mastcam, on Curiosity, Mastcam-Z can zoom in or out (hence the “Z”) and take stereo images and video. Mastcam, also designed with the help from Bell’s team, only has one wide angle and one telephoto lens.

“They’re spectacular, but it’s hard to do stereo,” Bell explains. “With Mastcam-Z, we improved on that by making both cameras capable of being wide-angle or telephoto (so) we can make stereo (images) at any scale we want.”

Mastcam-Z has taken more than 207,000 high-resolution images so far, and from these, created 39 360-degree panoramic mosaics.

Where to next?

“We are the science eyes of the rover,” says Bell, who got his start as a postdoc in the mid-1990s working on the Pathfinder mission, which landed Sojourner on Mars. Sojourner was “a printer-sized rover that communicated with its nearby lander,” he says. “I knew a lot about cameras and other instruments, but I had never applied them to space missions because, frankly, it was a really lean time for space in the ‘80s and early ‘90s.”

Bell has since helped develop and operate cameras for every rover that NASA has sent to Mars.

Mastcam-Z’s images are, of course, used for scientific research. But on a day-to-day basis, its “eyes” help the team decide where to go next and whether or not to drill into a rock at a particular spot.

“We're providing the context, the details on the environment in which these samples were obtained,” Bell says. “We're helping the rover drivers and the whole team figure out where to collect samples.

“Once we get somewhere and the instruments on the rover’s arm are in contact with the ground, we’re just cheering them on. Until we get there, we’re helping to find that spot. We are like a triage instrument. If you’re a doctor and you show up to some scene, like a tornado just went through, the first thing you’re going to do is triage: Who is hurt the most? Where can we help the most, at the highest level, as quickly as possible?”

When you land on another planet, you look around and there's an infinite number of places you could go. “How do you decide?” asks Bell, a consummate storyteller. “You need that assessment from triage, getting a quick look around and making a decision: Here’s where our goals should take us.”

On Earth, geologists also interpret rock formations and determine what occurred in the distant past. If you see "road cuts" in the highway or you look out of an airplane window at sand dunes and rivers in the desert below, that’s not that different from interpreting images of rock formations on Mars.

“It's forensics, like CSI: Mars,” Bell says. “You take pictures. You send samples to the lab. You’ve got all of these clues. We do the same thing on Mars, it's just that we can't be there ourselves.”

Bell not only designs the rovers’ high-resolution cameras but also directs the downlink operation team based at ASU. The currently all-female team processes pixel data as they come down from Mars, creates beautiful panoramic mosaics using multiple photos and assesses the health of the cameras, among other things.

For about two and a half months after Perseverance landed, the operations team worked rotating shifts on "Mars time" (a Martian day — or sol — is 40 minutes longer than Earth's), says Samantha Jacob, who received her doctorate under Bell and served on the team. “That meant we sometimes started at 3 a.m. and ended when people came in for a normal workday,” she adds. “Definitely some fun nights and long hours.”

Collecting pieces of Mars

One day in the not so far-off future, the team hopes they’ll be looking at pieces of Mars through microscopes, to do the kinds of science that can only be done on Earth.

“Ever since I was a graduate student, there was always talk in the science community about bringing samples back from Mars, and it was always a decade into the future,” Jacob says. “Now, with Perseverance collecting these incredible rocks, there's actually impetus to get the samples to Earth in the near future.”

During its first Martian year, Perseverance cached 10 sealed sample tubes, containing one each of the eight paired rock and regolith cores, as well as a tube containing Mars atmosphere and one tube containing a witness sample, at Three Forks Depot in Jezero Crater, a flat spot where a future spacecraft could land.

“If Perseverance has an issue and cannot deliver the samples that it is carrying on board, we can always go back to Three Forks Depot as a contingency and bring those samples back,” explains Wadhwa. “But the sample suite aboard Perseverance is the one that represents the most sample diversity to address our highest-priority science questions, and so remains of greatest interest for possible return to Earth.”

“The Apollo missions brought samples from the moon, and over the last 50 years, they've been analyzed by thousands of researchers worldwide,” says Wadhwa. “When Mars samples come to Earth from a world that has a potential for life, it’s going to be of interest to the broadest community that we can imagine: biologists, climate scientists, modelers, theorists, even philosophers and humanists.”

It’s an exciting time for scientists and science enthusiasts alike.

“We want to be some of the first teams in the world who are analyzing these rocks and soils brought back from Mars,” says Bell.

It is only through detailed analyses possible in state-of-the-art Earth-based laboratories, such as those at ASU, that scientists will be able to answer age-old questions about the nearest habitable world to Earth. The resulting discoveries could transform our understanding of the universe.

More Science and technology

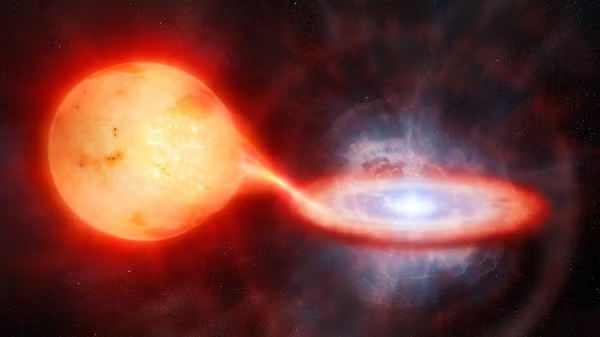

Astronomers observe ultra-hot nova with unexpected chemistry

A team of astronomers, including Arizona State University Regents Professor Sumner Starrfield, has uncovered an exceptionally hot and violent eruption through the first-ever near-infrared analysis of…

Statewide initiative to speed transfer of ASU lab research to marketplace

A new initiative will help speed the time it takes for groundbreaking biomedical research at Arizona’s three public universities to be transformed into devices, drugs and therapies that help people.…

ASU research seeks solutions to challenges faced by middle-aged adults

Adults in midlife comprise a large percentage of the country’s population — 24 percent of Arizonans are between 45 and 65 years old — and they also make up the majority of the American workforce…