New study finds the American dream is dying in big cities

The Phoenix skyline in Arizona. Photo courtesy of ASU Enterprise Brand Strategy and Management

Cities have long been celebrated as places of economic growth and social mobility, but new research suggests that their role in fostering opportunity has changed dramatically.

A new study led by Dylan Connor, associate professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University, finds that large, growing cities are no longer the gateways to upward mobility they once were. Instead, smaller towns are increasingly where economic advancement happens, while urban sprawl locks in disadvantage.

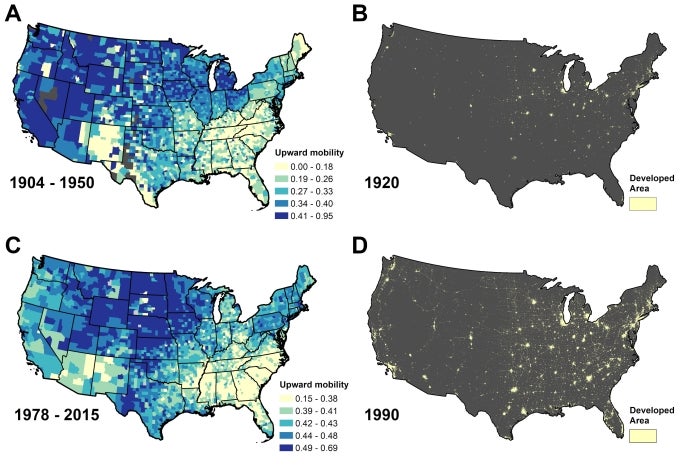

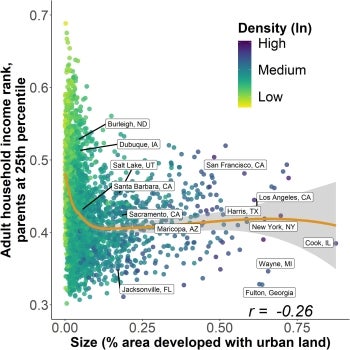

By analyzing 100 years of urban development across the United States, the study examines how city size, density and neighborhood connectedness have influenced social mobility across the 20th century. The findings reveal that while dense cities once provided pathways to prosperity, that relationship has weakened. Increases in population density between 1920 and 1990 are now linked to declining intergenerational mobility — the opposite of trends seen in earlier decades.

The study also shows that urban expansion, which once reduced inequality, now exacerbates it. Growing cities also see declines in social capital, measured through indicators like civic engagement, community ties and friendship networks. The researchers suggest that these weakening social connections may help explain why large cities are no longer engines of opportunity for all.

Connor’s research team includes colleagues both within and outside ASUPeter Kedron, courtesy affiliate, Institute for Social Science Research; Siqiao Xie and Garima Jain, both geography PhD candidates in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning; Jiwon Jang and Yilei Yu, both GIS PhD candidates in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning; Amy Frazier, professor, Department of Geography, UC Santa Barbara; and Tom Kemeny, associate professor, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto.

ASU News spoke with Connor to learn more about the study’s key findings and their implications for urban planning efforts.

Note: Answers may have been edited lightly for grammar, length and/or clarity.

Question: Your team used satellite imagery and historical data to track how U.S. cities have changed over the past century. How does this approach provide new insights into inequality compared with traditional studies?

Answer: When people think about the factors that might drive children’s long-term economic prospects — such as education, careers, parenting, schools, jobs and the economy — they often overlook the role of urban development.

In our work, we studied the development of every city in the United States over the past century. We then used data on millions of parents and children over this period to examine how the lives of otherwise similar children differ based on the type of town or city where they grew up.

We found that children tend to fare very differently depending on where they grow up — specifically, the city's size, density and neighborhood connectivity significantly shape children's career and educational prospects, often in surprising ways.

Q: The study reveals that as U.S. cities grow, they don’t always create equal opportunities for everyone. What were the biggest surprises or takeaways in how city size and design affect economic mobility?

A: We found that children from poorer backgrounds tend to achieve higher rates of upward economic mobility in smaller cities than in larger ones. This is surprising because big cities increasingly have the highest-paying jobs and the most prestigious schools and universities — yet many of the children who grow up in large places don’t benefit from those resources.

You can picture this by imagining two very different kinds of cities: Phoenix and Flagstaff. Phoenix is a vast, sprawling metropolis with a great variety of neighborhoods, while Flagstaff is smaller and has fewer people per square mile. Due to their differing growth patterns, neighborhoods in Phoenix and Flagstaff are quite distinct.

In smaller places like Flagstaff, children are more likely to play outside, interact across socioeconomic backgrounds and have parents engaged in the community. Data shows that Flagstaff residents are twice as likely to volunteer in local organizations compared with those in Phoenix. Our study suggests that children from modest backgrounds fare better in smaller, more tight-knit places than in larger cities.

Another striking result is how this pattern has reversed over time. In the early 20th century, large cities fostered economic mobility, benefiting industries and working-class families. But by the mid-20th century, this reversed — big cities increasingly provided opportunities for the affluent, while low-income children lost ground.

Q: Many people believe big cities offer the best chances for success, but your study suggests otherwise for low-income families. Why do smaller cities and rural areas provide better opportunities for upward mobility?

A: Success in today’s economy increasingly requires children and young adults to develop skills either at a college or in a trade. The early years of life are crucial in developing the skills, mindsets and self-belief that are needed to achieve this upward mobility. This development process seems to depend more on your community and neighborhood than what was previously believed.

Lower-income urban neighborhoods have fared increasingly poorly in this respect, so much so that the children in smaller cities and rural areas — places with fewer economic opportunities — are now faring better than their big-city counterparts.

Smaller towns often have more integrated schools, where children of professionals and working-class families mix.They also tend to have stronger community ties and family cohesion — factors that significantly impact children’s long-term success. These influences are particularly beneficial for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Q: Your study highlights the role of city structure — size, density and connectivity — in shaping economic opportunities. What lessons can urban planners and policymakers take from this research?

A: We need to rethink how cities are designed to support child development. Creating spaces where children can play safely, fostering strong community networks and encouraging civic engagement can help. The idea of “child-friendly cities” is gaining traction in urban planning, but these efforts are still at a relatively early stage and there's still much work to be done.

Also, there is a push right now to increase the population density of cities by building more houses and apartments. More housing would be beneficial, but it should be weighed against the cost of increasingly busier roads and streets, and with reducing the disruption to the many vibrant urban communities that already exist.

Q: What are the next steps for your research, and are there any ongoing or upcoming projects you’re involved in that could expand these findings?

A: I’m currently on sabbatical from Arizona State University and on a fellowship at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. I’m writing a book on which types of places best support children’s long-term growth and how that has changed over time. So watch out for that!

We are also conducting new research on the geography of wealth inequality, a largely understudied issue. My team has developed the first dataset tracking wealth disparities across cities and neighborhoods back to the 1960s. Over the next few years, there will be a lot more coming on that front.

More Science and technology

Newly identified viruses found in dolphins

In a new study, researchers from Arizona State University together with national and international collaborators have identified anelloviruses in dolphins for the first time. Anelloviruses are a…

ASU Interplanetary Lab celebrates 5 years of success

Five years ago, an Arizona State University student came up with the idea of creating a special satellite in what was then the newly built Interplanetary Laboratory. The idea was to design…

ASU secures NSF grant to advance data science literacy as demand soars

In an era where data permeates every facet of our lives, the importance of data literacy cannot be overstated. Recognizing this critical need, Jennifer Broatch, a professor at Arizona State…