Water expert drinks in ASU Regents Professor recognition

Amber Wutich, President's Professor and director of ASU’s Center for Global Health, has been named a 2025 Regents Professor. Photo courtesy of Academic Enterprise Communications

Hurricanes helped shape Amber Wutich's childhood.

Growing up in Miami, she was no stranger to their whirling winds and water. These wild storms would eventually inspire her work with water around the world.

“I grew up in hurricane culture and I experienced major storms like Hurricane Andrew,” said Wutich, an Arizona State University President's Professor and director of ASU’s Center for Global Health. “At that time, flooding would create a form of water insecurity. So we would experience intermittency and we would experience water shut-offs. We had to have water stored in bathtubs and canned water was distributed by FEMA. And so water insecurity, in a context of water abundance, was part of how I grew up.”

“And because I lived in a neighborhood where we had very strong social support networks, I felt that social infrastructure was a very visible way to survive,” said the 2023 MacArthur Fellow.

When Wutich went to graduate school, she was determined to take on a challenge that would have a significant impact on humanity.

“So that I could dedicate my life to doing important work,” she said. “And I felt that water was clearly a good choice.”

Today, Wutich, is a world-renowned expert on water insecurity. And her dedication to the field has earned her the title of ASU Regents Professor for 2025, the highest faculty honor awarded at ASU.

The title is given to ASU faculty who have made pioneering contributions in their areas of expertise, achieved a sustained level of distinction and enjoy national and international recognition for these accomplishments.

“My work focuses on understanding how humans survive when there's not enough water,” Wutich said.

Wutich directs the Global Ethnohydrology Study — a long-term, cross-cultural research project that examines how different communities deal with water-related issues. Wutich also leads Action for Water Equity, a participatory convergence study that develops collaborative water solutions within water-insecure U.S. communities.

During her 22 years of community-based fieldwork, Wutich has explored how people respond, individually and collectively, to extremely water-scarce conditions.

It is this dedication to meaningful research that led to many honors. Last month she was named the Big 12 Professor of the Year; she's been named the Carnegie CASE Arizona Professor of the Year; and she has raised more than $80 million in research funds.

Magda Hinojosa said that Wutich is not just a first-rate expert on water insecurity, but she has launched new fields of scholarship in the areas of water insecurity measurement, water and global mental health, and household water.

“It is no exaggeration to say that Professor Wutich has defined the study of water insecurity,” said Hinojosa, dean of social sciences for ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “Amber is a dynamo.”

Wutich learned that she had earned a place among ASU’s select group of Regents Professors in October.

“Michael Crow called me to a meeting of ASU leadership and announced it, and there was an enormous picture of my head.” she recalled. “It was very exciting. I was so honored to have my work highlighted in this way.”

Uncharted waters

Wutich has studied water in more than 20 countries.

“I'm an anthropologist, and participant observation is one of our core methods,” she said. “That means that our body is the core instrument of data collection and we embed in a culture and learn to live in that culture very profoundly over a long period of time.”

One of the first cultures that Wutich immersed herself in was Cochabamba, Bolivia. She was 24 when she arrived in July 2002 and worked there over a period of three years.

“We (anthropologists) have to learn the language, the mannerisms, the beliefs, the ways of being,” she said. “And that's what I did in Bolivia. I lived in an informal settlement, which is a place where people construct their own homes and over time construct their own utilities. But at the time that I was there, they did not have complete utilities. And so water service was a particular challenge.”

Her research required Wutich to experience the struggle over water in the same way the people of Bolivia did.

“Learning to live in such a different way produced many ridiculous errors on my part,“ she said.

“Because I did not know how to cook. I did not know how to bathe myself. I did not know how to use or flush the toilet. So if you can imagine that I am an adult woman trying to get other adults to teach me to do these things that a toddler would appropriately learn to do with this culture.”

One day Wutich was documenting a seasonal river that ran next to the community where she was living in Bolivia. It was used for multiple purposes.

"One day, we were upstream at the head of the river, where the freshest water was, and there was a taxi stand and drivers were washing their taxis. And then downstream from the taxi stand was a group of women washing their families' clothes. And then downstream from there was someone using the river as an open air toilet.

“And then further downstream was a mother washing her toddlers,” she recalled. “At that time, I was just thinking that the way of using this shared water resource put people at significant health risk. And that was worth noting.”

Testing the water

In Cochabamba, a water war had been won by the people who opposed the privatization deal and were experiencing very bad water insecurity. Wutich worked in partnership with communities and organizations throughout the region.

“Things reverted back to the old system, which was very inequitable and unjust,” she said. “So I went to work with those communities to understand how they survived in the aftermath of winning a water war, but not improving their water situation.”

Wutich’s work yielded some very unexpected findings about how people survive when water is very scarce, including forming water-sharing networks and establishing informal markets that had unregulated water vendors that would go door to door selling water.

“These were very intriguing findings,” she said. “What we didn’t know 20 years ago was to what extent these were universal mechanisms that people were using to cope with water insecurity. The Global Ethnohydrology Study was born out of my work as an anthropologist at this time.”

The study was an effort to design cross-cultural research to determine if these kinds of coping strategies are intercultural or if not, and under what conditions they emerged.

The work was supported by ASU because Wutich was a postdoc hired into the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation under archaeologist Professor Chuck Redman and ASU Regents Professor Nancy Grimm.

“They supported me in creating this very moonshot idea of a project,” she said. “Anthropologist and ASU Regents Professor Alexandra Brewis Slade mentored me to build the cross-cultural infrastructure, because she was already working with a network of sites around the world. She suggested that we merge my idea with her network and build this global collaboration.”

“I really did not think it was going to pan out at all,” she recalls. “I saw it as a sidelight project that was very high risk. And likely low reward. But I imagined it as a way to test ideas that were very difficult to test. And just see what happens. When you don't have high expectations, you're willing to take a risk.”

Wutich worked over a three-year period in Bolivia to better understand how communities were using water and surviving. From there, she scaled up to larger and larger communities, ultimately researching 28 sets of communities in the country.

“After I confirmed that those findings were robust,” she said, “I scaled up again. And that was when we began to do cross-cultural research.”

She eventually had study sites around the world. While the locations and cultures differed dramatically, the findings were remarkably similar.

“When we looked at that research in 21 sites around the world, we found every single water-insecure site had this water sharing. In some sites, as many as 80% or more of the households were engaging in this water sharing. So it was quite exciting that this hidden, near-universal coping strategy had become revealed through this cross-cultural research. The same similarities existed around informal water vending."

The project was surprisingly successful.

“It bore an enormous amount of fruit,” said Wutich, who has authored more than 200 papers, and co-authored six books including "Lazy, Crazy and Disgusting: Stigma and the Undoing of Global Health."

“Many, many papers, many new methodological innovations for how to do research cross-culturally. Wonderful intellectual collaborations. And ultimately, it helped create the groundwork for the water insecurity experiences network that is now an international network of scholars and partners that participates in cutting-edge modern security research.”

Wutich, water and Arizona

In addition to researching water scarcity around the world, Wutich is also looking at Arizona.

Currently, she is working on the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative under the leadership of Dave White, ASU associate vice president for research advancement. The project is being supported by the state with a $40 million investment that gives them the capacity to work with water-insecure communities in Arizona and test ways of building integrated, engineered and social infrastructures.

“We're partnering now with communities throughout the state, helping them build these integrated systems in ways that reflect their values and improve their lives,” she said.

And of course, her students also reap the rewards of her research.

“To me, there's nothing more important than scientific discovery, and research methodology is the backbone of those exciting discoveries,” she said. “It's such a joy to teach students how to become researchers.

One of her most popular classes is called “Disaster!” — which sounds scary but is actually solution-oriented.

“We have so much fun thinking about the really hard experiences that many humans face, and many of us will face increasingly under climate change, and how we can make our communities better by being better prepared, less vulnerable and more resilient. It is a class about a very serious topic that gives students a lot of hope, whether they are working in disaster response or in the U.S. military or simply as regular citizens who want to make their communities a better place,” she said.

That was what Wutich wanted to do when she started out as a graduate student and that is what she has continued to do. And it is why this year she was one of only three members of ASU’s faculty to become a Regents Professor.

"She has been a champion and an advocate for advancing social science perspectives on environment issues, whether it be water or climate, in the global health or a variety of different arenas,” said White, who directs ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation and has co-authored more than 20 papers with Wutich.

“She has really contributed at every level of ASU, and then beyond that, she's developed an incredible network of partners around the world,” he said. “She's connected with researchers at American universities and globally, as well as government institutions and multilateral institutions like the United Nations. She has brought her scholarship and that impact-driven perspective to communities not only here in Arizona, but all around the world.

"I'm so proud to have been part of her journey … and watched her emerge as one of ASU's most important scholars and leaders.”

More Science and technology

Study finds cerebellum plays role in cognition — and it's different for males and females

Research has shown there can be sex differences between how male and female brains are wired.For example, links have been made between neurobehavioral diseases — such as attention-deficit/…

Artificial intelligence drives need for real data storage innovations

In southeastern Mesa, Arizona, construction crews are hard at work on a state-of-the-art data center. The $1 billion facility will open in 2026 and provide approximately 2.5 million square feet…

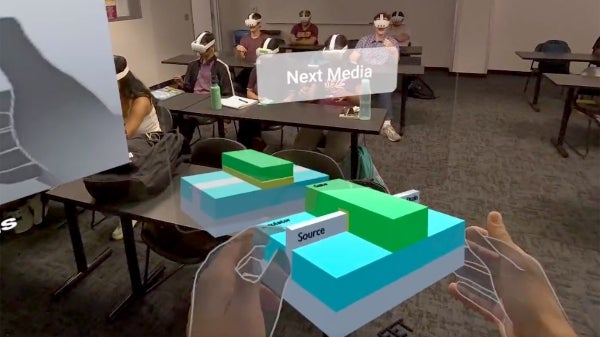

Extended reality class prepares students for semiconductor industry

Semiconductor manufacturing is a complex and fast-changing field, driven by innovation and investment to meet growing societal demands.For engineering students interested in joining this industry,…