Author Tommy Orange delves into historical research for 'Wandering Stars'

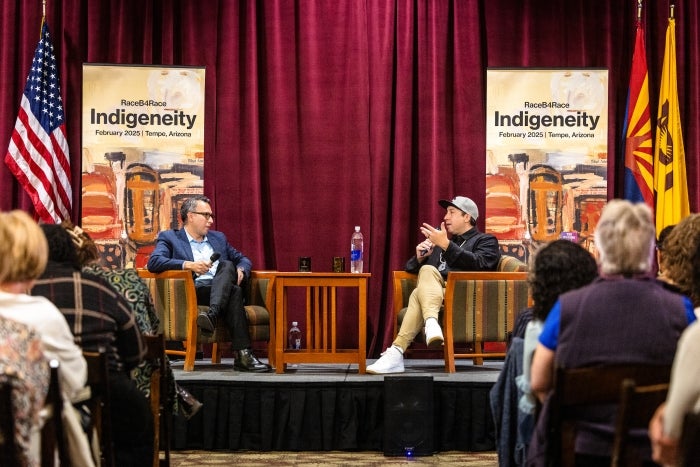

Author Tommy Orange discussed the historical research he did for his most recent book, "Wandering Stars," during a keynote talk on Saturday, Feb. 8, as part of the two-day RaceB4Race: Indigeneity event at Arizona State University. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Author Tommy Orange, who won acclaim for his 2018 book “There There,” about urban Native Americans, told a crowd at Arizona State University on Saturday night that he never intended to write a sequel based in historical fiction.

But after a series of serendipitous events, “Wandering Stars,” released in 2024, became a historical story of how Native Americans suffered and survived.

“I was writing a pretty straightforward sequel and it picked up right where ‘There There’ left off,” he told the crowd in Carson Ballroom at Old Main. His talk was the keynote of the two-day RaceB4Race event, a conference series sponsored by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies in partnership with The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Division of Humanities and the Hitz Foundation.

“I had resisted writing historical anything because it’s been overdone to death and continues to be a depiction of us in the past tense,” Orange said.

But he happened to be in Sweden to oversee the translation of “There There” in 2019 and was invited to a museum that had Native American artifacts.

“I was given this weird tour where the museum people were really aware of how problematic they are now,” he said.

They showed him some regalia of his tribe, the Southern Cheyenne, and he noticed a newspaper clipping that mentioned members of his tribe living in Florida in 1875.

“Why would we be in Florida?” he wondered of his Oklahoma-based tribe.

“So I started researching. And I knew I wanted to include this in the sequel.”

He discovered that after the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado in 1864, many Southern Cheyenne and other Native Americans were taken as prisoners of war to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. There, Richard Henry Pratt, an Army officer, forced them to suppress their culture and become soldiers, learning to march and studying the bible. Pratt was the architect of forced assimilation of Native Americans, including the notorious boarding schools for children.

“I tend to over-research, partly to avoid writing but to convince myself that I’m still working,” Orange said.

“There are a ton of real facts from a lot of research.”

The research uncovered several coincidences.

He had already decided to call the sequel “Wandering Stars” — for a reason that he called “embarrassing.” He was signing thousands of copies of “There There” in a warehouse and the song “Wandering Star” by Portishead came on.

“I decided that was the name of the sequel,” he said. “It’s the most uninspiring way to think of something. I’m just a ‘90s emo kid.”

Then his research revealed that the Fort Marion prison was shaped like a star, and when he saw a list of Native American prisoners there, one was named Star. Another was named Bear Shield — the name of a family featured in “There There.”

“There were signs that this title was fitting,” he said.

“There There” followed several Native American characters living in Oakland, California, where Orange was born and raised, and ended with violence at a powwow.

“Wandering Stars” is about the ancestors of some of those characters and also picks up the plot after the powwow, exploring themes of isolation and addiction.

He opened his talk with a reading from “Wandering Stars,” including this passage in the voice of one of the prisoners, who read the Epistle of Jude in the bible:

“It seemed to me that what had happened, what was happening to my people, was what the book was about. … ‘Raging ways of the sea honing out their own chain, wandering stars to whom is reserved for blackness and darkness forever.’”

Orange said he was not a reader or a writer while growing up, but after he started working in the Native American community in Oakland after college, he realized that the stories of urban Indians needed to be told.

“What are Native people like me like?” wondered Orange, whose mother is white and whose father is a native speaker of Cheyenne.

“I knew there weren’t a lot of people like this depicted.”

Orange said that the erasure of Native Americans continues.

“Native people are still understanding the ways that it’s not our fault, and in this massive piece of land we continue to not be here even though we’re here,” he said.

Orange has completed a screenplay for a movie and is working on a third novel — both unrelated to his two released books.

He said that the current political chaos sometimes makes him feel powerless.

But he is not hopeless.

“That’s the themes of this symposium — that this is a moment where voice is incredibly important. I believe in the power of art and how it can effect change,” he said.

“That’s the only thing I can do.”

More Arts, humanities and education

Autism diagnosis leads ASU professor to write book about neurodiversity and literature

Bradley Irish always knew his mind worked differently.But it wasn’t until two years ago that Irish, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s Department of English, discovered why.He was…

ASU professor, Arizona inmate work to rehabilitate the 'imprisoned mind'

An Arizona State University professor has collaborated with an Arizona inmate on a book that examines why investing in healing prisoners would benefit everyone.“Imprisoned Minds: Lost Boys, Trapped…

Illuminating legacy at ASU

In 2020, the ASU Art Museum unveiled a groundbreaking installation, "Point Cloud (ASU)," by renowned artist Leo Villareal. The art piece was given a permanent home on the Tempe campus in 2024 thanks…