Decades of data show age plays an important role in primate reproduction

Gelada female in Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Photo by Shayna Lieberman

There are a lot of factors that affect whether a baby gelada monkey or chacma baboon survives its first year of life, including a mother’s experience, food sources and infanticide. Recently, scientists at Arizona State University conducted a study to determine if maternal age might also play a role in primate reproduction.

“When a new male comes into a social group or rises to alpha status, they will often kill the babies they did not father in order to speed up a mother’s reproductive cycle so that they can father their own children,” explained Jacob Feder, a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow with the Institute of Human Origins.

“When a female primate is really young, she might be inexperienced, she might not have completed growth yet, so she's juggling more things going on just in terms of where she can allocate her energy. Then, at the tail end of the lifespan, we have these moms who are a bit more frail, and sometimes (their offspring) can be encumbered because a lot of them end up orphans.”

Feder and colleagues analyzed over 30 years' worth of data about infant survival and birth intervals with geladas and chacmas to determine if the reproductive aging curve is present in these two primates, even alongside outside factors that affect the survival of their babies, such as infanticide.

“Infanticide has such a big effect on reproductive outcomes that what's going on under the skin (young females being immature, older females being weak) might not 'show up' in the data. But it did show up in our data! So maternal age clearly still matters, even in these two species where a lot of risks seem to be outside of mom's control.”

In addition, there was something in the data that was surprising: Although both primates are faced with infanticide and maternal aging, babies of young gelada moms survived more than others.

Feder wanted to know why.

He explained it may have something to do with what gelada moms are eating: grass. Geladas live in high-altitude environments and eat grass year-round. These chacmas live in the lush Okavango Delta system and eat anything. Other members of the species live in very dry deserts.

“Because grass is ubiquitous across the gelada landscape, maybe moms are just a bit more nutritionally buffered than they are in other species,” Feder said. “A lot of species that show these young mom advantages eat leaves. Maybe there is something about these diets that are driving these aging patterns that hasn’t really been explored yet, and we want to dig deeper.”

Feder says it's important to look at data about primates like baboons and monkeys, not just chimpanzees, so we can get a larger picture of different social structures and see how this may play out in humans.

“Humans have this kind of remarkable life history pattern,” he said. “We want to understand how exactly that came about. Why do we have these long lives where we have kids relatively fast, given the fact that we are so big-bodied? So by looking at some of the things that are driving the variation in how we reproduce and when we reproduce across our lifetimes, (as well as those of) our close relatives, we can get a better sense of how humans ended up the way that we did.”

The article “Female reproductive ageing persists despite high infanticide risk in chacma baboons and geladas” is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science. Additional authors include India Schneider-Crease, assistant professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change; Joan Silk, research scientist at the Institute for Human Origins and Regents Professor; and Noah Snyder-Mackler, associate professor at the School of Life Sciences.

More Science and technology

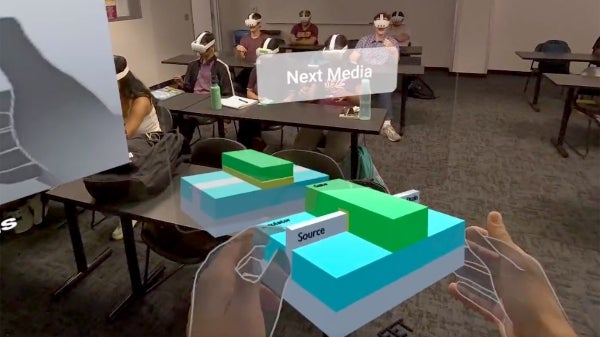

Extended reality class prepares students for semiconductor industry

Semiconductor manufacturing is a complex and fast-changing field, driven by innovation and investment to meet growing societal demands.For engineering students interested in joining this industry,…

ASU, AAAS launch collaborative to strengthen scientific advancements

Today, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and Arizona State University announced a five-year partnership, the AAAS + ASU Collaborative. Together, the institutions will…

Scientists discover unique microbes in Amazonian peatlands that could influence climate change

Complex organisms, thousands of times smaller than a grain of sand, can shape massive ecosystems and influence the fate of Earth's climate, according to a new study.Researchers from Arizona State…