Floods linked to rise in US deaths from several major causes

iStock photo

New research, co-authored by Arizona State University Assistant Professor Aaron Flores and published in Nature Medicine, uncovers a concerning link between severe flooding and increased death rates in the United States.

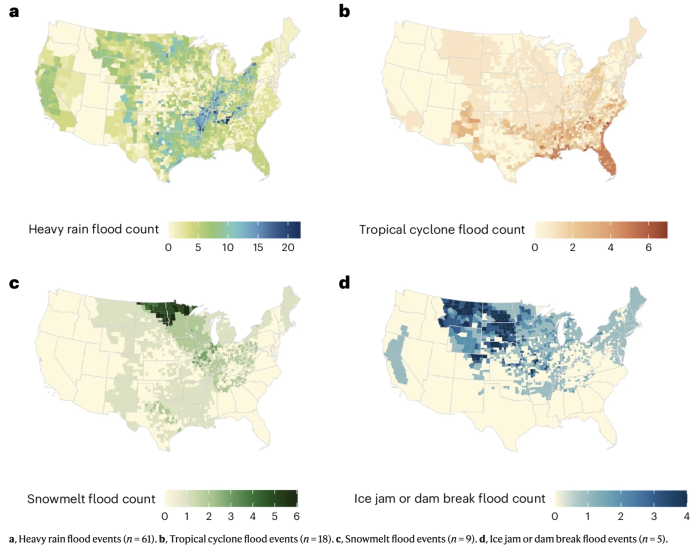

By analyzing 35.6 million death records spanning the past two decades, the study revealed that large floods were linked to up to a 24.9% rise in deaths from major causes — including cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases and injuries — even in nonhurricane-related floods caused by heavy rain, snowmelt or ice jams.

The findings underscore how socially vulnerable populations — particularly older adults and women — face heightened health risks during and after severe flood events. With climate change and rapid population growth escalating flood hazards, the study emphasizes the urgent need for effective public health strategies to protect at-risk communities.

We spoke with Flores to learn more about his role in the study and how its findings can inform future public health and urban planning efforts.

Question: You collaborated with researchers across multiple institutions. What was your role in this groundbreaking study on flood-related mortality, and how did your expertise contribute to the findings?

Answer: I provided expertise on the social vulnerability of different populations, particularly concerning gender and age. Given my background in environmental justice, I helped interpret the study's findings through the lens of how age — especially the elderly — and gender impact health outcomes during and after flood events. I worked closely with the team to highlight key disparities in flood-related mortality. My contributions focused on ensuring that our results underscored the need for targeted policies and interventions to protect these populations, specifically in the context of large flood events.

Q: The study highlights significant health impacts from nonhurricane-related floods, such as those caused by heavy rain and snowmelt. Why do you think these events have been historically overlooked in public health research?

A: Hurricane-related floods often dominate public attention and research because they are typically large-scale events with widespread physical, economic and public health impacts. Their size and the immediate devastation they cause make them more visible and urgent for policymakers and researchers.

In contrast, floods caused by heavy rain or snowmelt tend to be smaller and more localized. These events may not garner as much attention because their impacts are dispersed across smaller areas, and they may not generate the same level of media coverage or policy urgency.

Additionally, heavy rain and snowmelt are not explicitly accounted for in FEMA flood-risk maps, which focus more on riverine and coastal flooding. This may contribute to an underestimation of their risks in public health and disaster planning.

From a research perspective, these types of floods may also be overlooked because they can be more challenging to systematically study. Their impacts might not be as immediately apparent or easy to quantify, and they often lack the long-term data collection and analysis efforts that hurricanes receive. However, as our study shows, these events can still have health consequences, emphasizing the need for more comprehensive approaches to understanding and mitigating flood-related risks.

Q: Were there any findings from the study — whether related to specific flood types, mortality causes or regional patterns — that particularly surprised you?

A: Yes, one of the most surprising findings was that snowmelt-related floods were associated with increased death rates for nearly all causes of death, even for mild flood events. This contrasts with other flood types, where mortality increases were typically larger during severe and very severe events. We think this could be an artifact of the longer duration of snowmelt flood events compared to other flood events (e.g., heavy rainfall and tropical cyclones), even though the flooding itself may not be severe.

Q: The research emphasizes long-term mortality impacts rather than immediate flood-related deaths. Why is it important to focus on these extended timelines?

A: Focusing on long-term impacts is important because floods affect health through both immediate and delayed pathways, often with compounding effects over time. Acute impacts such as drownings and injuries are the most visible. However, the delayed impacts such as respiratory illnesses from mold, infectious diseases from contaminated water, or cardiovascular issues exacerbated by stress are also important but less apparent. Floods can also disrupt critical infrastructure, limiting access to health care, food and shelter. These disruptions are likely to have long-lasting effects that can contribute to indirect health effects that emerge weeks, months or even years after the initial flood event. By focusing on the long-term impacts, we can better understand the full scope of flood-related health risks and develop more comprehensive public health strategies.

Q: The research points to the intersection of environmental hazards and social vulnerability. What proactive steps can policymakers, public health officials, urban planners and researchers take to better protect vulnerable populations during and after floods?

A: We need to engage directly with affected communities through targeted outreach. Policymakers can prioritize equitable infrastructure investments such as upgrading drainage systems in socially vulnerable communities and providing resilient and affordable housing. Public health officials can focus on community-based preparedness programs, ensuring that vulnerable groups — like the elderly and those with limited mobility — have access to resources before, during and after floods. Urban planners can enhance their use of social vulnerability data by ensuring it informs not just flood-risk assessments but also the prioritization of mitigation efforts and infrastructure upgrades.

Q: With the projected rise in flood exposure due to population growth and climate change, what proactive measures can local governments and urban planners take to build resilience and improve infrastructure in flood-prone areas?

A: One of the most critical measures is to stop new development in flood-prone areas. However, we need significant funding at all levels of government to assist those already living in high-risk areas who cannot afford to relocate. This includes investments in buyout programs, flood-proofing homes and community resilience projects. We also need stricter building codes and zoning regulations to ensure that any new development in less risky areas is designed to withstand future flood risks.

Q: How do you see the study’s findings informing urban planning efforts, especially in regions like Arizona and the broader Southwest, which face unique environmental challenges?

A: We definitely have unique challenges in terms of flooding. Our region experiences low-frequency but high-magnitude rainfall events that can cause rapid flash flooding, especially during monsoon season. This combination of fast-draining soils, steep terrain and dense urbanization amplifies the impacts of even short rainfall events. As one of the fastest growing regions in the country, it’s critical that urban planning efforts in the area are prepared for these heavy rainfall events. Currently, these types of events are not well accounted for in FEMA flood maps, which means planners must proactively incorporate local knowledge and alternative data to ensure that new developments and infrastructure can withstand these unique risks.

Q: Looking ahead, what are the next steps for this research, and are there any ongoing or upcoming projects you’re involved in that will build on these findings?

A: We’re very interested in expanding this research to explore how other sociodemographic factors, such as race and ethnicity, influence health outcomes after flood events. Previous research has consistently shown that race and ethnicity are linked to disproportionate health impacts after major floods, but it would be a major contribution to this area of research to investigate how these disparities differ based on flood type, severity and over time. For example, are disparities growing or shrinking in the face of climate change and evolving flood risks?

More Environment and sustainability

From ASU to the Amazon: Student bridges communities with solar canoe project

While Elizabeth Swanson Andi’s peers were lining up to collect their diplomas at the fall 2018 graduation ceremony at Arizona State University, she was on a plane headed to the Amazon rainforest in…

From environmental storytelling to hydroponics, student cohort crafts solutions for a better future

A select group of students from Arizona State University's College of Global Futures, a unit within the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, is laying the foundation to drive change…

2 ASU faculty elected as AAAS Fellows

Two outstanding Arizona State University faculty spanning the physical sciences, psychological sciences and science policy have been named Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of…