Harvesting satellite insights for Maui County farmers

The team from the Kerner Lab, a research center in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence at Arizona State University, visits a farm in the island of Maui in Hawai'i. The researchers are using artificial intelligence to share NASA satellite insights with Maui farmers. Photo courtesy of the Kerner Lab

Food sovereignty can refer to having access to culturally significant foods, but Noa Kekuewa Lincoln believes it goes farther than that.

“I think the concept goes beyond the foods themselves to having some control over the food system, ” he says. “Local people are also seeking an agricultural system that is just and equitable, ecologically sustainable and produces crops that support a healthy lifestyle and landscape.”

Lincoln is an assistant professor of Indigenous crops and cropping systems at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He is an expert on the history of Hawaiʻi agricultural practices.

Prior to European contact, Lincoln notes that the Hawaiian Islands were completely food secure and self-sufficient. But today, for complex reasons, including tourism and agribusiness issues, approximately 90% of food consumed on the islands must be imported. Grocery costs in Hawaiʻi are the highest in the nation, with a gallon of milk costing $7.65 on average, while the national average is around $4.

In the Indigenous Cropping Systems Laboratory, Lincoln studies traditional farming practices and how they might be applied to stimulate current agricultural production and promote food security and sovereignty on the islands.

But farmers in Hawaiʻi face serious and significant obstacles.

Computer science researchers in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, are hoping insights from the satellite data they collect might be able to help.

From satellites to sweet potatoes

Ana María Tárano is a research assistant professor in the Fulton Schools who studies human-centered machine learning, creating artificial intelligence that prioritizes human needs and values. Working under the supervision of Hannah Kerner, an assistant professor of computer science and engineering, Tárano leads the production of the Maui Nui Crop Monitor.

A team in the Kerner Lab, including Tárano, has developed AI tools capable of aggregating and analyzing data from NASA satellites and extracting useful information for Maui farmers.

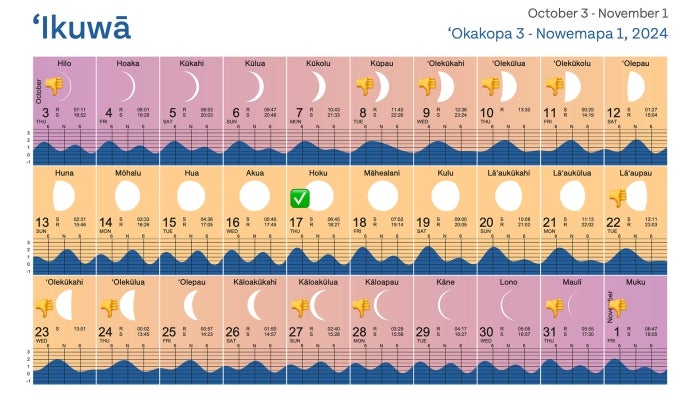

Using AI, the researchers are able to gather information about crops such as climate data, temperature conditions and soil moisture. The results are translated into the Maui Nui Crop Monitor — a newsletter assembled by Tárano that includes maps, charts and graph data designed to help farmers maximize the success of their irrigation, planting and harvesting patterns. The team also created the first high-resolution cropland maps of Maui County using machine learning, a type of AI where complex algorithms learn from data and make predictions.

The newsletter is distributed via email to hundreds of farmers and other stakeholders on the islands of Maui County. It provides continually updated information about agricultural conditions, planting guidance and opportunities from the County of Maui Department of Agriculture.

The work is funded in part by grants from NASA Acres, a food security consortium of farmers, ranchers and other stakeholders that uses satellite data to strengthen U.S. agriculture.

Tárano emphasizes that the team’s goal is to provide helpful data that supports the community-driven efforts of Maui farmers.

“One of my favorite parts of the project are the community check-ins,” Tárano says.

From a quick form in each newsletter or through direct emails from community members, the Kerner Lab researchers receive crucial feedback from the Maui farmers, collecting data points about the accuracy of their information and any images farmers might supply.

“It’s really important that the community tells us whether the information is useful,” Tárano says. “So, we always want to invite the community to share what they’re going through or just tell us what they think about the newsletter.”

Using new tech to address an old problem

“The situation didn’t happen by accident,” Christopher Nakahashi observes wryly.

Nakahashi is a lecturer of Hawaiʻi ethnobotany at the University of Hawaiʻi Maui College.

He says that the challenges facing contemporary farmers in Hawaiʻi have deep historical roots. Early Polynesians likely arrived with so-called canoe crops, including niu (coconuts) and maiʻa (bananas). They eventually developed robust farming systems for other produce such as kalo (taro), ʻuala (sweet potatoes) and ʻulu (breadfruit).

At the time of the arrival of Captain James Cook, the Hawaiian Islands might have had a population of up to 1 million people (the current population is approximately 1.4 million). Aboriginal Hawaiian farmers were able to feed the entire group.

A large threat to Native Hawaiian farming came from the whaling industry from around 1820 to 1860. To feed foreign sailors, large tracts of farmland and forest were cleared for cattle grazing. In 1848, when foreign settlers were allowed to purchase land, enormous parcels were obtained for sugar and pineapple exports, leaving little remaining for traditional sustainable farming. The new crops were more water-intensive and triggered a massive diversion of water from Hawaiʻi’s natural rivers and streams.

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893 marked a significant decline in traditional farming and control of the land by indigenous peoples.

Today, Nakahashi says that due to the pressures of tourism, a huge American military-industrial complex and issues relating to climate change, farmers in Hawaiʻi face a unique set of challenges, including the small amount of available land, water scarcity and high costs of operation.

Helping farmers make decisions and take actions based on their environment and resources is an important objective of the Kerner Lab team.

Computing the perfect cucumber

“We stopped at the market, and I bought a cucumber from the farm. It was so delicious that I knew I had to work here,” jokes Hiroshi Suzuki.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Suzuki was a software engineer stationed at a global tech company in Silicon Valley. The tough times made him rethink his career choices. Inspired by his boyhood love for his grandfather’s farm back in Japan, Suzuki and his wife moved to Maui and sought roles at the Okamura Farm in Kula.

When Suzuki connected with Tárano and the Kerner Lab team at a farmers market, he immediately understood the value of their project.

“On Maui, we are constantly monitoring the weather, and we call it micro weather because if you drive maybe five minutes or 10 minutes, the weather can be very different,” Suzuki says. “Public weather forecasts are not that useful. The newsletter Ana is issuing gives us very location-specific weather information.”

Suzuki says that the Maui Nui Crop Monitor is especially helpful in planning water usage. The farm uses evapotranspiration data from the newsletter to determine how much water to supply to fields. Overwatering can lead to pests and root rot, while underwatering can cause wilting and stunted growth. The Okamura team also receives farm-specific data from NASA satellite images, which assists in crop management.

The Okamura Farm has been in the Okamura family for three generations and transitioned to growing certified organic produce in 2000. The farm hopes to play a role in improving food security, offering high-quality produce such as broccoli, zucchini, cabbage and tomatoes at reasonable prices through farmers markets. They are also attempting to become a local supplier for major stores and are one of the top providers of lettuce to Whole Foods in Honolulu.

A mission that matters

The researchers hope to expand the newsletter, improve their connections with local farmers and continue to collaborate with organizations like NASA Acres.

The work underway holds personal significance for Tárano, who was born in Cuba.

“Cuba has favorable conditions for its crops, yet many people are food insecure,” she says. “I have seen firsthand what happens when there is a lack of food security. Food is important because it’s a basic human need. But it’s also the way that culture gets passed down and the way we find comfort.”

Lincoln agrees.

“Agriculture is tied closely to human values,” he says. “At one time, agriculture was our medicine box, our schools and our land management system.”

The new AI-powered Maui Nui Crop Monitor hopes to honor the Hawaiian legacy of community-based, sustainable agriculture.

Lincoln says early Indigenous farmers were innovators who used their ingenuity to feed large numbers of people.

“Native Hawaiians had a tremendous diversity of agricultural approaches,” he says. “From the creation of flooded, irrigated terraces to food forests to super marginal development in the lava flows, the Indigenous farmers developed a tremendous spectrum of self-sustainable farming forms.”

More Science and technology

ASU student-run podcast shares personal stories from the lives of scientists

Everyone has a story.Some are inspirational. Others are cautionary. But most are narratives of a person’s path, sometimes a circuitous one, from one point in their lives to another.A new podcast…

The meteorite effect

By Bret HovellEditor's note: This story is featured in the winter 2025 issue of ASU Thrive.On Nov. 9, 1923, Harvey Nininger saw his future explode across the Kansas sky. He would become perhaps the…

Why your living environment defines how people perceive you

Stereotypes are pervasive.We've all heard of stereotypes based on gender, race, age or religion. But what about making an assumption about someone's personality based on their ecology?According to a…