After pursuing a PhD to study evolution, ASU grad leaves committed to tackling vector-borne diseases

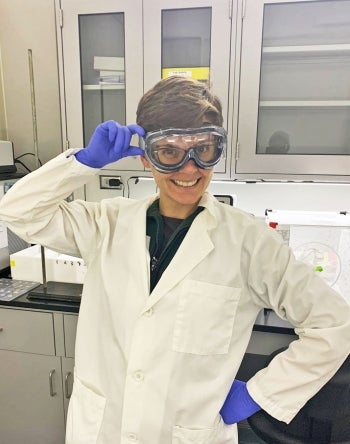

Mosquitoes in these bottles are being exposed to different levels of insecticides, or none at all. Brook Jensen conducted this experiment as part of a project to understand how insecticides spread in a mosquito population.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable fall 2024 graduates.

When Brook Jensen was an undergraduate, she actively sought out as much research experience as she could.

Through the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, she found opportunities to do a wide array of research on some really interesting species: she studied how the genomes of rhododendrons influence the plant’s structure and function, how tilapia survive in environments with extreme salinity and low oxygen levels, and even how embryonic exposure to cocaine impacts the development and behavior of zebrafish.

Those experiences ignited Jensen’s passion for biology research; she was certain she wanted to make a career out of it the second she finished her bachelor’s degree at California State University, Stanislas.

“I didn’t really care which organism I was studying,” Jensen said. “I was more interested in the kinds of questions that I could explore.”

Jensen got accepted to the evolutionary biology program at ASU in the Center for Evolution and Medicine. She joined The Hujiben Lab, which studied an organism that makes most people recoil: mosquitoes.

Specifically, her work looked into different mosquito control techniques, which are a crucial global health measure, as mosquito-borne diseases cause hundreds of thousands of human deaths each year.

“I had no prior insect research experience coming in … Now that I’ve been in a mosquito lab, I’m really passionate about mosquitoes, vector biology, public health and everything in that realm. I would really like to stay within this same type of work.”

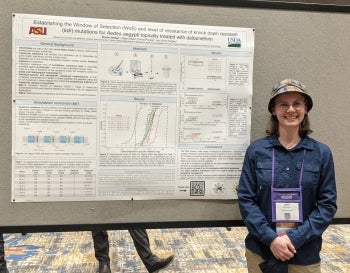

Jensen specifically studied how mutations that confer resistance to insecticides, or chemicals meant to kill mosquitoes, spread within a population of mosquitoes. That involved studying whether carrying those mutated genes harmed or benefitted mosquitoes in ways beyond making them resistant to insecticides. Most mosquito control researchers assume that resistance genes harm mosquitoes’ chances of surviving or reproducing in some way, but Jensen has done work demonstrating that’s not always true.

“The prospect of those genes actually conferring a fitness benefit is concerning,” she said, “because it could mean that resistance spreads more easily in the population.”

Jensen also tested how different insecticide treatments affected the rate at which resistance spread in a population of mosquitoes. The most common method of vector control involves applying a really high dose of an insecticide to an area to try and quickly kill all of the mosquitoes there. That comes with the risk of increasing the spread of resistance in a population faster, though, because only the mosquitoes who are resistant to the insecticide will be able to survive and reproduce. So, Jensen tried out a couple of different strategies, and compared them to both a high dose of insecticide and no dose, as controls.

The first strategy was a low dose of insecticide, which Jensen found killed a small number of mosquitoes and kept resistance levels down. The second strategy involved exposing half the mosquito population to a high dose of insecticide while leaving the other half untreated, leaving them as a “refuge” that allows mosquitoes who are not resistant to the insecticide to survive and reproduce. That strategy should maintain higher genetic diversity, slowing the spread of insecticide resistance.

“These strategies show that we should possibly rethink how we use insecticides. A higher dose is not always better,” she said.

Outside of her research, Jensen has been extremely involved in her graduate student community and other extracurricular activities. She has served on the School of Life Science e-board — or graduate student government — as the event coordinator, a member of the mental health committee and the treasurer. She put together a graduate student hiking group in her first year, has organized two Evolutionary Biology Research Symposiums and has mentored 19 undergraduate students in the lab. Two of those were students who came through the Research Experiences for Undergraduates program, which she says feels especially full circle.

“That was really nice to give that experience back to other people.”

Question: What are your plans after graduation?

Answer: I will be moving to New Hampshire with my fiancé, who also just graduated. We started at the same time –– he was in my advisor’s husband’s lab, also studying mosquitoes, so that’s how we met. We’ll be moving to New Hampshire and staying with his family to take a little break and enjoy finishing. Then we’ll start applying for postdoc positions.

My dream job at the moment is working at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. So that’s where I hope I will end up, or somewhere similar

Question: What’s your favorite spot on campus, whether for studying, meeting friends, or just thinking about life?

Answer: Probably the lab. If I was working late at night in the lab, and other people were there, that’s when I had some of the most intellectually stimulating and fun conversations.

Question: What’s the best piece of advice you’d give to those still in school?

Answer: I don’t know about best piece of advice, but just a piece of advice is that it’s OK to not know the answers. And it’s OK to ask for help.

More Sun Devil community

Supporters show their generosity during Sun Devil Giving Day 2025

Thousands of Arizona State University supporters from across the globe came together on Sun Devil Giving Day on March 20 to give to scholarships, research, student programs and university initiatives…

New ASU women's basketball coach has sights set on championships

Molly Miller apologized for being a few minutes late for her Zoom interview Sunday afternoon.No apology was necessary.It’s been a crazy and hectic 72 hours for Miller, who guided Grand Canyon…

SolarSPELL wins 'best in show' award at South by Southwest

Arizona State University professors from a variety of disciplines made a big splash at the South by Southwest festival of technology and culture in Texas earlier this month.The ASU SolarSPELL…