Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

Covers of three of ASU Professor Robert Boyd's publications. "Culture and the Evolutionary Process," and "Not By Genes Alone" cover images courtesy of The University of Chicago Press. "A Different Kind of Animal" cover image courtesy of Princeton University Press.

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural evolution fields have grown.

Culture — how information is socially shared and passed to others — isn’t just found in humans, but other animal species as well.

“Human cultures keep changing and changing and changing. And pretty soon, you end up with complicated stuff. There aren't any animal populations, including chimps, that go that far,” said Boyd, a research scientist at Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins and a professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

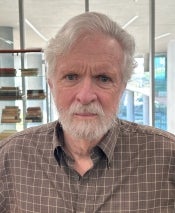

After 40 years, numerous research papers and eight books, Boyd is a forerunner in the field of cultural evolution. That’s why, in November, the journals Science and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) asked Boyd and his colleague, Professor Peter Richerson, to write essays about the topic.

“Cultural evolution: Where we have been and where we are going (maybe)” was published in a special feature of PNAS, and “Culture in humans and other animals” was published in Science.

ASU News spoke with Boyd about his life’s work and the recent commentaries.

Editor's note: Answers have been edited for length and/or clarity.

Question: What is cultural evolution and why is it important?

Answer: If you think about these 2- to 3-million-year-old australopithecines like Lucy, they were typical apes right? They lived in a small part of Africa, they used simple tools. All animals are different, and every species is unique, but they (australopithecines) were a lot like other organisms.

If you think of humans now, we have the widest geographical range of any species. There isn’t any other terrestrial species that comes close. Humans are really good at adapting to a wide range of habitats. And we do that through a bunch of stuff — tools and local knowledge. But we don’t acquire that knowledge the way other animals do.

Humans adapt as populations to local circumstances, and we do it by learning from each other. Think about making a kayak; it's a really complicated process, and no individual is going to figure out how to do it on their own. But we learn it over generations, bit by bit; it’s way beyond the inventive capacity of individuals.

The human trick is we figured out how to adapt culturally, and we do that by accumulating knowledge over multiple generations.

So if you want to understand how humans got from australopithecines to, you know, downtown Phoenix, you need to account for all this nongenetic adaptation. I wrote a book that gives a brief introduction to all of this called "A Different Kind of Animal.”

Q: What is the key takeaway from your essay “Culture in humans and other animals”?

A: Science asked us to write this commentary to set the recent paper in context. It's about chimpanzee culture, and it shows there is a correlation between how much genetic exchange there is between chimp populations and how culturally different they are. And the authors interpret this to mean that these differences have accumulated.

What Richerson and I have been arguing for a long time is that that’s the key to understanding why humans are so different from other animals. Humans adapt culturally and other organisms don’t.

Over the last 15 or 20 years, more and more examples of intermediate cases of animal nonhuman culture have popped up, and Richerson and I review that. So the conclusion is, I think that there’s a lot more animal culture than we thought there was 20 years ago. But still, it's pretty different from humans — animals still don't accumulate very much.

Q: What is the key takeaway from your essay “Cultural evolution: Where we have been and where we are going (maybe)”?

A: This paper is a history of the field of cultural evolution and an introduction to the special volume of PNAS. It's a history of how it got started and what the original questions were.

If you think like I do — that cultural adaptation is the key to why human evolution has gone the way it’s gone — you can’t understand human evolution without having a theory of how a cultural organism evolves. In the book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” we pose the question, “How can it ever be a good thing to just copy a random individual from the previous generation?”

I’ve done mathematical models that show exactly why this can be the case. Why, sometimes, natural selection can favor a psychology that causes you to just imitate the first person you run into, or your parents.

And so, if that’s right, then understanding human evolution is about understanding how we made this transition from a regular primate to this cultural primate, in which humans are completely addicted to cultural adaptation.

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…