Don't believe what you hear: ASU professor weighs in on voice cloning technology

Voice cloning's potential misuses include election fraud, identity theft and misinformation. Photo courtesy of iStock/Getty Images

Due to advancements in voice cloning technology, the potential to misuse it for election fraud, misinformation, impersonation and identity theft has escalated.

Visar Berisha, an associate dean of research and commercialization in Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, was invited to participate in a roundtable discussion about voice cloning in Washington, D.C., this month.

The discussion, held by the United States National Security Council, looked into the applications of voice cloning along with its potential misuses. More than 20 experts from academia, industry and government participated.

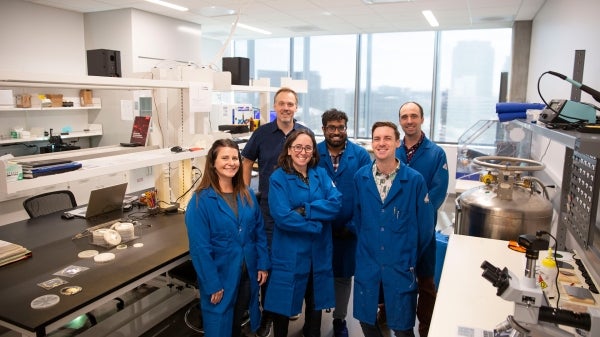

Berisha leads a team that recently was one of the winners of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission's Voice Cloning Challenge.

His team, which includes fellow ASU faculty members Daniel Bliss, a Fulton Schools professor of electrical engineering in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, and Julie Liss, College of Health Solutions senior associate dean and professor of speech and hearing science, developed an instrument called OriginStory, a new type of microphone that verifies a human speaker is producing recorded speech and then watermarks the speech as authentically human.

ASU News spoke with Berisha, who is also a professor in the College of Health Solutions, about the issue.

Editor's note: The following interview has been edited for length and/or clarity.

Question: Before we get into how this technology can be used by bad actors, let’s define it. What is voice cloning?

Answer: Voice cloning refers to this technology that’s been developed recently where I can take a very brief snippet of your voice, maybe 30 seconds or a minute, and generate a digital replica. And with that digital replica, I can create audio samples of you saying anything I want.

Q: How easy is that to do?

A: Anyone can do this. So you would find a recording of me — I think there are YouTube videos of me giving a lecture, for example — and download it. Then you would go to a company like ElevenLabs. And on that website, you’d put in a credit card — I think it’s like $5 a month — upload the short clip of my voice, and then you would use it to generate whatever audio you wanted to generate. One of the conditions of using that website, I think, is that it explicitly asks if you have permission from the person to do this. So there are some steps companies are taking to prevent people from doing this. But overall, it’s still quite easy.

Q: You don’t even need to hear a person’s voice to do it? You can get it off social media platforms?

A: That's correct. You can do this by just downloading a person's voice online and generating this digital replica.

Q: How long has this technology been around?

A: The technology itself has always existed. People have been doing this for a decade, but it sounded very robotic. Now, you’re sort of hard pressed to tell the difference between real and fake. Until very recently, whenever you heard speech, the only place where it could have possibly come from is another person’s mouth. You’re always willing to trust it. But that’s changing now. The (technology) is getting much, much better.

Q: This sounds like it’s ripe for misuse. Are there any potential benefits to the voice cloning?

A: There are conditions where people end up losing their voice as one of the symptoms; ALS, for example. If you have some historical speech from that person, you can create their replica and with a digital device, they can push a button and say in their replica voice, “I need water,” or something like that. The question is, at what point for these technologies does the negative side outweigh the positive side? I’m not really sure. If you ask me, there’s probably more harmful applications of this technology than there are positive applications. But I don’t know that that’s going to stop its development.

Q: Can you give me some examples of those harmful applications?

A: There have been several stories where people have used it to coerce or trick elderly parents into thinking their kids or grandkids are in trouble and they need to send money. During the primaries, there was an individual who cloned President (Joe) Biden’s voice. It was used in robocalls, encouraging people not to vote. You can imagine that on election day, having cloned voices from election officials saying, “Hey, don’t bother going to this voting precinct because it’s closed.” Or, “The lines are five hours long. If you haven’t gone there yet, don’t bother going."

Some of the scenarios that keep me up at night are these high stakes applications. For example, before an airplane takes off and as it lands, it talks to air traffic control. These air traffic control channels are totally open. You can download an app right now and listen to any air traffic control station anywhere you want. Those channels are not very secure. So you can envision some coordinated deepfake attack where you have people injecting deepfake audio into these channels and, best case scenario, sort of halting air traffic. Worst case scenario, you’re talking about a terror attack.

Q: Is there technology being developed that could prevent this sort of fraud?

A: Yes, there are a couple of different approaches to this problem. One way to think about this is, “Well, people are doing this at scale, so what we need to do is build AI (artificial intelligence) systems that can tell the difference between what’s real and what’s fake.” But the fact of the matter is, it’s really difficult to do that because these models are getting so much better so quickly. There’s this cat and mouse game where the good guys are now developing detectors, but they’re going to be outpaced very, very quickly because the number of bad guys working on different types of technology is so great.

Another approach is, we’re going to rely on these companies that are developing this technology to watermark AI-generated content. But bad guys are not going to include watermarks. So we’ve sort of flipped this on its head and said, “Well, instead of watermarking AI generated content, what if we watermark human-generated content?”

Q: That's how OriginStory works, correct?

A: Yes. A new type of microphone that we’ve developed can do this. It’s a standard microphone that records voice acoustics along with a secondary set of sensors that measure all the things that are happening inside the human body as a person speaks. If you think about what you need to do in order to speak, you first take a breath, and then you get this air coming from the lungs and exciting the vocal pulses, which results in vibration. Then you end up moving your lips and your tongue and your jaw in order to produce these sounds that you pick up with a microphone.

So now with this microphone, we simultaneously measure the bio signals, the things that are happening inside the body and the voice acoustics, to prove with high certainty that they’re coming from inside a human.

Q: Would the microphone be installed in cellphones?

A: One of the limiting factors in having impact with this technology is that you need really good partners in order to be able to disseminate it at scale. We’re talking to some of the large mobile phone manufacturers in order to include the technology within mobile devices. With that microphone installed, now you can be sure that anything that comes out of the phone is stamped as authentically human.

Q: Last question: How prevalent do you think voice cloning will become over the next few years, and how worried are you about that potential spread?

A: I’ve been tracking trends of voice cloning technologies, and I’m not seeing any plateau in these trends. We’re sort of at the point of exponential increase, where the technology is widely available and people can very easily make use of it. I think, over time, people will start developing some vigilance because they’ll know of its existence and they’ll be less likely to trust things. I think that will certainly help.

More Science and technology

ASU professor honored with prestigious award for being a cybersecurity trailblazer

At first, he thought it was a drill.On Sept. 11, 2001, Gail-Joon Ahn sat in a conference room in Fort Meade, Maryland. The cybersecurity researcher was part of a group that had been invited…

Training stellar students to secure semiconductors

In the wetlands of King’s Bay, Georgia, the sail of a nuclear-powered Trident II Submarine laden with sophisticated computer equipment juts out of the marshy waters. In a medical center, a cardiac…

ASU startup Crystal Sonic wins Natcast pitch competition

Crystal Sonic, an Arizona State University startup, won first place and $25,000 at the 2024 Natcast Startup Pitch Competition at the National Semiconductor Technology Center Symposium, or NSTC…