Editor’s note: This story is part of a series exploring how ASU tackles complex problems to create a thriving future.

Count all the deaths from hurricanes, tornadoes and floods, and you still won’t match the destruction wrought by one invisible weather disaster — extreme heat.

In Arizona’s Maricopa County, 645 people died of heat-related causes in 2023, a 52% jump from the previous year. But Arizona’s most populous county isn’t the only place contending with a growing number of heat fatalities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates extreme heat claimed 2,302 livesThe national total may not account for all Maricopa County deaths due to different methods used to calculate heat-related deaths on the national and local levels. nationwide in 2023, three times the average heat-related deaths in the country from 2004 to 2018.

Despite the toll of high temperatures, neither the Federal Emergency Management Agency nor a U.S. president has ever declared a major disaster or emergency in response to heat. This is largely because the 1988 Stafford Act, which authorizes the federal government to declare a disaster or emergency, does not include extreme heat among its list of 16 major disasters.

Read more

Check out more heat and weather-related content.

At Arizona State University, researchers are bringing visibility to the deadly issue of extreme heat. Scientists and scholars from a range of disciplines are working with communities to measure and understand extreme heat and the risks it poses. They also guide policy that protects lives and well-being in an increasingly warm world.

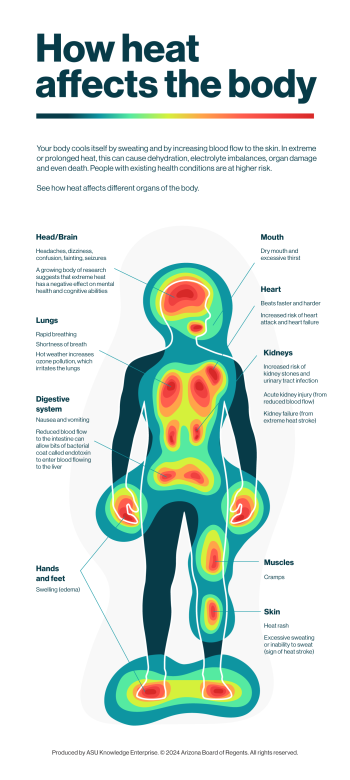

Extreme heat’s effect on your body

Extreme heat can have devastating effects on the human body. As temperatures soar, your body works overtime to cool down and your organs may struggle to perform essential functions. Prolonged heat exposure can lead to dizziness, disorientation and fainting and, in extreme cases, organ failure and death.

Fundamentally, the human body’s response to extreme heat comes down to a volume problem, according to Dr. Pope Moseley.

“We have about 15 liters worth of arteries and veins and five liters of blood. So, you're constantly shunting blood around to send it where it's needed,” says Moseley, an intensive care physician and research professor in ASU’s College of Health Solutions. “When you're exercising, you transfer blood to the muscle. When you're cooling, you transfer blood to the skin. When you're exercising in the heat, you're transferring blood to muscle and skin, and you just don't have a lot of volume.”

In heat stroke cases, when the body transfers massive amounts of blood to the skin to cool off, this reduces blood supply to essential organs. When the human body reaches 38 degrees Celsius or 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit, the blood supply to the intestine drops by about half. This can cause the intestinal epithelial barrier — which regulates nutrient absorption and keeps bacteria at bay — to fail. Bits of bacterial coat called endotoxin can then enter the blood flowing to the liver. This triggers an inflammatory cascade that can eventually cause multi-organ failure.

But Moseley says heat stroke and heat exhaustion only account for a tiny fraction of heat’s total impact. Heart failure, mental illness, respiratory diseases, sepsis and strokes are just a few of the other ailments that worsen when extreme heat is a factor.

“If there's a heat wave, the hospital fills up, but it doesn't fill up with heat illness,” says Moseley. “That is the really pernicious issue with heat — it affects so many things.”

During his time at the University of Copenhagen, Moseley and his colleagues developed machine learning tools that could predict the risk of death for individual patients based on previous hospitalizations and existing health conditions. At ASU, he’s applying a similar approach to heat risk.

Mosely and Marisa Domino, also a professor in the College of Health Solutions, are using hospital and population data to study the wide range of conditions exacerbated by heat. They plan to develop an app to help people understand their individual vulnerability to extreme heat. Their work could help hospitals better manage resources during extreme heat events.

“For every one person with heat stroke, there are 10 people coming in for something else,” Mosely says. “We can't match health resources to what is needed until we understand what are the drivers that are going to put people in the hospital. This heat is a disaster, and we need to treat it as such.”

Hot summer in the city

Phoenix frequently makes headlines for streaks of 110-degree-plus days or record-high temperatures. To Erinanne Saffell, the Arizona State climatologist, these data points are noteworthy — but not groundbreaking.

“In 1896, Parker, Arizona, experienced four days of 120 degrees or higher — it’s happened before,” says Saffell, who directs the Arizona State Climate Office, which evaluates and synthesizes data and research relevant to the state’s climate.

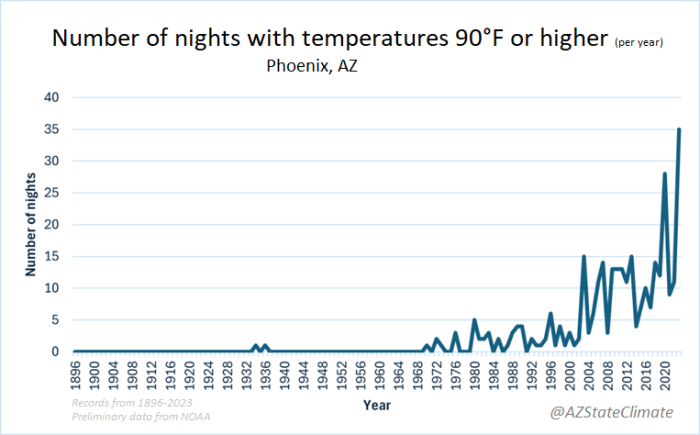

She is more concerned about nighttime temperatures. Nighttime lows don’t dip as they used to, largely due to increased urbanization, especially in places like Phoenix. The buildings, pavement and concrete act like a solar oven — soaking up heat throughout the day and releasing it long into the night.

Cooling the heat island

ASU’s Southwest Urban Corridor Integrated Field Laboratory is pioneering new ways to mitigate the urban heat island effect by integrating high-resolution observations, community engagement and modeling.

This urban heat island effect has caused Phoenix’s nighttime lows to slowly creep up since the 1990s. The current record for the highest nighttime low is 97 degrees on July 19, 2023.

“These high nighttime temperatures are especially dangerous, because if you can't cool off your body at night, then that heat can accumulate in your body and the next day you're more at risk,” says Saffell, a senior Global Futures scientist with ASU’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory. “And we get a lot of attention in Maricopa County, but it's everywhere. Sedona has an urban heat island. Benson has an urban heat island. Tucson has an urban heat island.”

Because it is such a local issue, city governments are looking to curb the worst impacts of extreme urban heat. In 2021, on the heels of another sweltering summer, the city of Phoenix established the Office of Heat Response and Mitigation. Publicly funded and integrated into the city government structure from the start, the first-of-its-kind office is charged with responding to and alleviating the effects of extreme heat in Phoenix.

David Hondula, an associate professor in ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, directs the office. He says his goal is to improve citizens’ everyday interactions with heat, from heat exhaustion and heat-related fatalities to high energy bills, the walk across a hot parking lot or touching a blazing-hot seat belt buckle.

“We're hoping to see improved outcomes across the board in the community related to heat, and we're hopeful to achieve those through changing the dialogue, changing the processes, changing the thinking in city government,” Hondula says.

For example, the office is collaborating with the city’s public health advisor to address the challenges that lie at the intersection of heat, homelessness and substance use. Last year, 45% of the heat-related deaths in Maricopa County were people experiencing homelessness and 65% involved substance use.

Ongoing efforts include training partners within the homeless resource system to connect clients with heat-safety resources and educating people on the dangers of substance use in extreme heat.

Phoenix also expanded the hours of some cooling centers where people can go to get out of the heat. By early July 2024, the five cooling centers with extended hours saw more than 10,000 visits, according to Hondula.

Heat help

Find resources to stay cool across Maricopa County.

“We know it is a need that has been unmet in the past, and we're really proud to have been able to make this big step this year,” he says.

The Office of Heat Response and Mitigation has also overhauled Phoenix’s 2010 Tree and Shade Masterplan. Funded by $50 million in local, federal and private sources over the next five years, the new Shade Phoenix Plan aims to plant 25,000 new trees and build 500 new shade structures.

The effectiveness of tree cover in lowering temperatures is well documented. One ASU study found that increasing the tree canopy from 10% to 25% could reduce the temperature of a typical Phoenix neighborhood by 4.3 degrees Fahrenheit. Saffell believes better tree cover could also lower nighttime temperatures.

“Trees not only block sunlight from hitting surfaces that soak up heat — roofs, sidewalks, parking lots — but they put off water into the atmosphere, which is a cooling process called transpiration,” Saffell says. “That keeps our environment from getting too hot at night.”

A better way to measure heat

The way we design and build urban environments can lessen the risks for individuals. The materials, amount of shade, urban forms and vegetation are all key factors in how comfortable people feel outdoors in hot climates. But before we can design and build cooler environments for people, they must be accurately measured.

“We have weather stations at the airport, so we know what the air temperature is, but people don't live at the airport,” says Ariane Middel, an associate professor in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering and the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence.

Air temperature isn’t the best way to measure heat exposure, as it doesn’t account for all the factors that contribute to heat load on the human body. Middel’s SHaDE Lab focuses on measuring mean radiant temperature, or MRT, to better understand how humans experience heat. MRT is the average temperature of all surfaces surrounding a person.

“In hot, dry environments such as Phoenix, the mean radiant temperature is probably the most important measure for people's experience of heat because it includes direct and reflected thermal and solar radiation,” Middel says.

To capture MRT, Middel uses MaRTy, a rolling instrument station that measures air temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, and location to accurately measure how someone might experience heat in a given area.

Since 2016, Middel has used MaRTy to inform a range of studies, including determining the cooling effect of light-colored pavement in a Phoenix neighborhood, mapping the most comfortable pedestrian routes, finding the best type of shade and more.

The station’s usefulness inspired Middel to expand MaRTy’s family. Working with the city of Tempe, Middel has been installing miniature versions of MaRTy — dubbed MaRTinies — in local parks. Equipped with some of MaRTy’s standard sensors and a computer vision-enabled camera, a MaRTini watches for activity to see how people use parks depending on the heat.

The project will allow the city to better allocate resources and increase shade and other cooling measures based on the usage of the spaces, Middel says.

When MaRTy met ANDI

While MaRTy can measure the heat load on the human body in a given situation, it can’t tell us how the human body will react. That’s where ANDI comes in.

ANDI is a life-sized manikin that can mimic the thermal functions of the human body thanks to sensors spread across 35 body zones. It is the first thermal manikin designed for use outdoors. ANDI can sweat, generate heat, breathe and shiver, providing researchers insight into how humans respond to extreme temperatures.

“We can put ANDI in these conditions that are dangerous for people and still investigate how the human body would react in a certain heat situation,” Middel says. “We like to say we have a full-service contract with ANDI.”

See MaRTy and ANDI go

MaRTy and ANDI — along with other novel instruments to capture microclimate data — contributed to a pair of recently published studies in the International Journal of Biometeorology and Science of the Total Environment.

Custom-fabricated by Thermetrics for ASU, ANDI is foundational in Konrad Rykaczewski’s quest to develop a model for human heat exchange and how different factors — such as age, clothing or medical conditions — impact heat regulation.

“The idea is to advance these models and validate them to the point that we can intelligently design garments and other cooling strategies to help people,” says Rykaczewski, an associate professor of mechanical engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

Understanding your personal heat risk

ANDI provides a general understanding of how heat affects the human body. But factors such as age, behaviors, medications, health conditions and even social support systems can greatly change the trajectory of someone’s health outcomes. We still have a lot to learn about these individual differences.

ASU researchers Jennifer Vanos and Gisel Guzman are looking to fill this knowledge gap. Their HeatSuite study uses smart devices, weather sensors and surveys to evaluate heat exposure, personal behavior and individual health outcomes of participants. The study is piloting in Phoenix and Montreal and will expand to Colombia and Australia in the future. The pilot is recruiting Phoenix-area participants for trials in August and September.

Share your experience with heat

Take a prescreening survey to see if you’re eligible to participate in the pilot study. Up to $200 in gift cards is available for participants.

“It’s really important to study the multifaceted way people experience heat, beyond just thinking about it when there are mortalities,” says Guzman, a PhD candidate in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning. “We really don't know how heat affects the everyday life of people and their well-being.”

The sensors and smart devices measure heart rate, wrist temperature, blood pressure, oral temperature, air temperature, humidity, wind speed and more. Participants also self-report heat perception, heat symptoms and hydration status. The suite of sensors was developed by Nicholas Ravanelli, an assistant professor at Lakehead University in Canada. The study’s global nature will allow the researchers to evaluate heat perception in different climates and inform heat adaptation strategies in different places.

“The climate is warming, and we need to find ways to adapt,” says Vanos, an associate professor in the School of Sustainability and a senior Global Futures scientist with ASU’s Global Futures Laboratory. “We cannot just focus on mitigation when adaptation is needed to protect people, especially the most vulnerable populations.”

Combating heat with community resilience

A 2023 study found that multiday power loss during a heat wave could double the estimated amount of heat-related deaths in Phoenix, Atlanta and Detroit. Mary Muñoz Encinas believes that in such dire situations, social connections can save lives.

“In the event of a heat emergency — any emergency, really — the first order of defense is your family, your friends, your neighbors,” she says. “Check in on them. ‘Do you have AC? Do you have power?’”

Muñoz Encinas is the program coordinator for ASU’s HeatReady Initiatives, which advance heat preparedness and resilience through free resources and education and aim to strengthen communities against the worst effects of extreme heat.

Get HeatReady

Are you an educator or community leader? Connect with HeatReady to find heat-related resources for your school or neighborhood.

The program began in 2017 as the master’s thesis of Adora Shortbridge, a then-student in ASU’s School of Sustainability, to help prepare Phoenix-area schools for extreme heat. It has since blossomed into a sweeping set of initiatives across 35 schools and community centers that advance heat readiness at the school, neighborhood and city levels.

At the city level, the program works closely with the Office of Heat Response and Mitigation in Phoenix, disseminating resources and developing learning programs.

“With neighborhoods, we take a needs-based approach,” Muñoz Encinas says. “At first, we just aim to start conversations, understand their priorities and concerns to connect them to relevant resources or develop action plans.”

HeatReady Neighborhoods also aims to establish community-based resilience hubs, which can serve as resource distribution locations during heat waves or other emergencies. The program is currently working with the city of Tempe on a grant application to transform the EnVision Center into a resilience hub.

For schools, Muñoz Encinas and the HeatReady team developed a Heat Ready scorecard for educators and students to evaluate their school’s heat preparedness and connect them with funding opportunities or other resources to address gaps. The program also develops education and training for students, teachers, medical staff and administrators on heat illness and exposure and awareness.

Paideia Academies, a Phoenix K–12 school, has worked with HeatReady and other ASU researchers for the past five years to transform their campus by replacing cement and other impermeable surfaces with vegetation, water features and bioswales for heat mitigation.

“I’ve just been so impressed with the whole ASU team and their work,” says Brian Winsor, executive director of Paideia Academies.

Policy we can all agree on

The Knowledge Exchange for Resilience is oriented around a simple idea: Research should enhance quality of life and create positive, lasting change.

To this end, Knowledge Exchange for Resilience (KER) — a unit of the Global Futures Laboratory — links community needs with research projects to build and sustain resilience in Maricopa County. KER’s efforts roughly span food and water systems, healthy communities, the built environment and economic security, with heat playing a role in all.

“There's always this dimension of the work that goes back to heat,” says Patricia Solís, the executive director of KER. “It’s one of those threat multipliers, and something that is really imperative that we center on when we're talking about resilience in Maricopa County.”

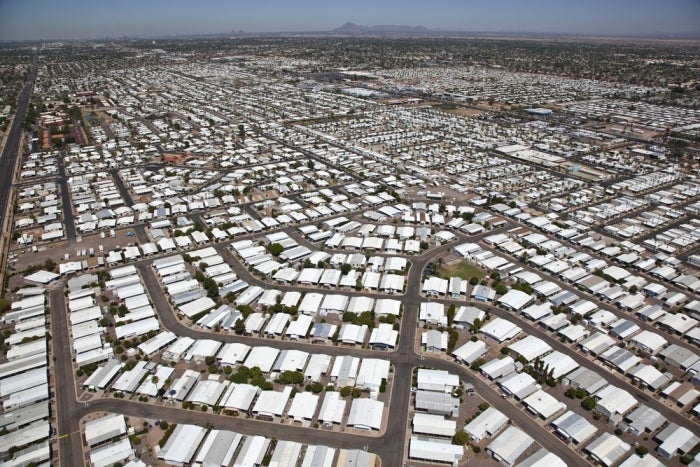

In 2018, KER researchers made a shocking discovery. While mobile homes and manufactured housing only accounted for 5% of housing in Maricopa County, 30% to 40% of indoor heat deaths occurred in mobile homes. KER forged community partnerships to identify why so many living in mobile homes were so vulnerable to heat. They produced a solutions guide for residents, landlords and city governments to address the issue.

But those solutions weren’t getting used everywhere. In some instances, landlords prohibited residents from installing air-conditioning units, shade structures and other cooling measures.

“I think a good policy recommendation is to not stop people from supporting themselves in any disaster,” Solís says. “You really need people to be prepared at their own household level. We should not prohibit those things.”

KER’s research was then used to inform proposed legislation, crafted by Wildfire, a Phoenix-based community action group aimed at ending poverty, together with AAMHO, the association representing residents of mobile and manufactured homes. In January, Solís testified before the Arizona House of Representative’s Commerce Committee about KER’s findings. Unanimously, the committee voted to move the bill forward, where it was again passed unanimously by both the House and Senate.

“In a place like Arizona, where sometimes it's hard to find what we agree on, this was something that we could all agree on,” says Solís.

The bill landed on Gov. Katie Hobbs’ desk April 2, 2024, where she signed it into law with an emergency order to put it into immediate effect. Today, landlords cannot deny tenants the right to install air conditioning or other cooling measures.

In addition to informing legislative solutions, KER’s research underpins a statewide strategy.

In August 2023, following 30 consecutive days of extreme heat advisories in three Arizona counties, Gov. Hobbs declared a state of emergency and issued an executive order to better coordinate future government responses to heat.

Drawing on years of research, engagement with state agencies, and the deep knowledge of community stakeholders, KER delivered a report to the Governor’s Office of Resiliency in January 2024, outlining recommendations for the state plan. The plan was released March 1 and included important recommendations, such as naming the nation’s first statewide chief heat officer.

Solís hopes the report — and KER’s model of community-generated heat resilience research — will find use outside of Arizona as communities around the world grapple with rising temperatures.

“Our solutions for Arizona can’t be adopted wholesale everywhere, but our process can,” she says. “Listening to the real questions our communities are asking so we can then tap into the intellectual power of our universities to research and design solutions — that’s the ASU model of doing research of public value.”

Funding sources

Ariane Middel’s MaRTinies project is funded by her National Science Foundation CAREER Award.

ANDI is funded by $200,000 from ASU and a $410,000 NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant. Ongoing research with the manikin is funded through a $2 million NSF Leading Engineering for America's Prosperity, Health, and Infrastructure (LEAP-HI) grant.

Jennifer Vanos’ HeatSuite study is funded by her NSF CAREER Award.

The Knowledge Exchange for Resilience was created with funding from the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust.

More Environment and sustainability

2 ASU faculty elected as AAAS Fellows

Two outstanding Arizona State University faculty spanning the physical sciences, psychological sciences and science policy have been named Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of…

Homes for songbirds: Protecting Lucy’s warblers in the urban desert

Each spring, tiny Lucy’s warblers, with their soft gray plumage and rusty crown, return to the Arizona desert, flitting through the mesquite branches in search of safe places to nest.But as urban…

Public education project brings new water recycling process to life

A new virtual reality project developed by an interdisciplinary team at Arizona State University has earned the 2025 WateReuse Award for Excellence in Outreach and Education. The national …