Assessing the red alert on corals

Beth Polidoro (left), associate professor in ASU's School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences and ASU–IUCN partnership lead, with her team after an inspiring exploration of the vibrant coral reefs in Fiji's waters. Courtesy photo

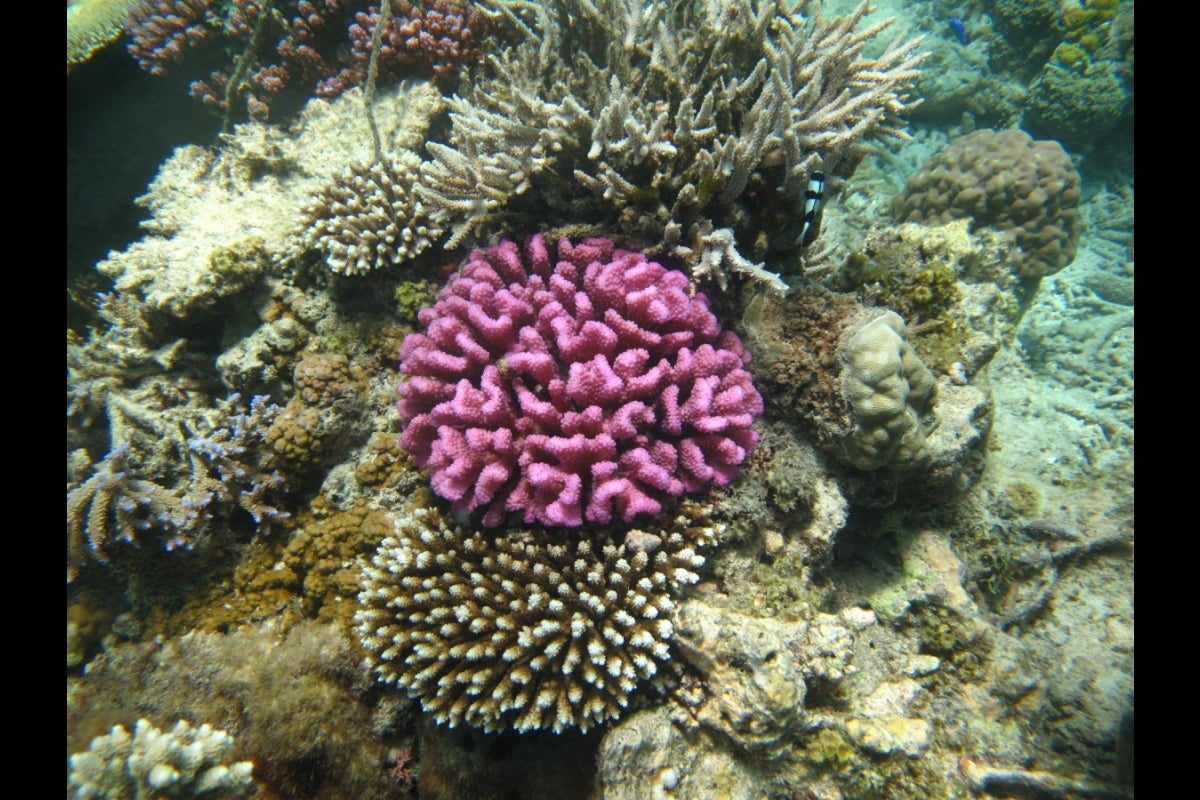

As our planet continues to warm, rising ocean temperatures threaten coral reefs across the globe. But not all corals are created equal, and some may be able to withstand higher temperatures or longer warming events.

In order to determine which species may be at the highest risk of extinction and which may be more resilient to local threats and climate change, Arizona State University Associate Professor Beth Polidoro and colleagues have been assessing the extinction-risk status of the world’s reef-building corals as part of a partnership with IUCN, an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources.

This comprehensive project seeks to evaluate roughly 850 coral species, with contributions from over a hundred coral experts from over 30 countries. Using the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as a guide, Polidoro, deputy director of ASU's Center for Biodiversity Outcomes and ASU–IUCN partnership lead, and her research teamPolidoro’s leadership, along with David Obura (founding director of CORDIO East Africa), Francoise Cabada Blanco (senior teaching fellow at the University of Portsmouth) and Christi Linardich (senior researcher in IUCN’s marine biodiversity unit), was instrumental in driving this international collaboration forward, with support from organizations such as the IUCN, MSC Foundation, National Geographic, CORDIO East Africa, Arizona State University and others. developed a robust assessment methodology. They conducted their first assessment of the corals in 2008, and are now conducting a second reassessment to see if any of their conservation actions have improved the status of corals globally — or if things are getting worse.

Here, Polidoro shares more about corals and her team’s findings.

Editor's note: Responses may have been lightly edited for length and/or clarity.

Question: Why are coral reefs important?

Answer: Coral reefs are some of the most diverse marine ecosystems on the planet, providing numerous services both for the marine environment and for people. Often referred to as the “rainforests of the sea,” coral reefs are home to an astonishing variety of marine life, including thousands of fish species, mollusks, crustaceans and other invertebrates. They serve as nursery grounds for juvenile fishes, help protect coastlines from storms and erosion, sequester carbon to mitigate climate change and support coastal communities across the globe.

Q: Are corals in danger?

A: In short, yes, very much so. One of the biggest threats to corals is oceanographic changes, such as increased sea surface temperatures due to climate change. When sea surface temperatures become just 1 degree Celsius higher for eight to 10 weeks of the year, massive coral bleaching can occur, which are really coral mortality events. With the increasing frequency and duration of these warming events, coral populations have less ability and opportunity to recover from these bleaching events.

Q: What have you found so far with your second assessment?

A: From the results of the Atlantic coral species, we know that the risk of extinction for Atlantic corals has doubled since the first assessment. For the Indo-Pacific species, we recently held a global assessment workshop at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum in Singapore. Singapore is at the southwestern corner of the Coral Triangle, which is the world's hot spot for coral reef biodiversity. Of the approximately 850 species of reef-building corals around the globe, the vast majority of them are in the Indo-Pacific. This workshop was the last step in this reassessment of the world's corals, which will all be published on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in November 2024.

Q: What does it take to assess the extinction-risk status of the world's reef-building corals?

A: Over the past five years, we consulted with more than 100 coral scientists across the globe to develop a robust methodology to assess the population status of individual coral species. This is unique, as most studies focus on overall live coral cover loss rather than species population declines. In the end, we used models of past coral cover loss and future predicted coral bleaching events from climate change models to estimate various scenarios of coral habitat loss over 30-year time frames. These scenarios were combined with species-specific traits related to resilience or vulnerability to different threats in order to calculate species-level declines over the past and into the future.

Q: What will happen if we lose coral reefs?

A: If we lose coral reefs, it will create a cascading effect, impacting global ocean health. Not only will marine species be impacted, but so will coastal livelihoods and humans who depend on oceans.

Q: How can our students and the community contribute to preserving the coral reefs?

A: The really scary part about the analyses we conducted was that, based on current models, even if greenhouse gas emissions were halted today, it would still take several decades just to stop increasing and only potentially stabilize global warming trends. In other words, we need to act now to reduce carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions. This means taking steps to look at our own individual energy use. This means driving and flying less, using energy-efficient appliances and LED lights, not wasting food and trying to eat locally. If you shop online, choose the slower shipping date as it can reduce trucks on the road, buy fewer new clothes and try to reuse or reduce our everyday products.

More Environment and sustainability

A 6-month road repair that only takes 10 days, at a fraction of the cost? It's reality, thanks to ASU concrete research

While Arizona’s infrastructure may be younger than its East Coast counterparts, the effects of aging in a desert climate have begun to take a toll on its roads, bridges and railways. Repairs and…

Mapping DNA of over 1 million species could lead to new medicines, other solutions to human problems

Valuable secrets await discovery in the DNA of Earth’s millions of species, most of them only sketchily understood. Waiting to be revealed in the diversity of life’s genetic material are targets for…

From road coatings to a sweating manikin, these ASU research projects are helping Arizonans keep their cool

The heat isn’t going away. And neither are sprawling desert cities like the metro Phoenix area.With new summer records being set nearly every year — 2024 was the warmest year on record for…