In the first line of her Wikipedia entry, Margarita Cota-Cárdenas is described as “a voice for Chicano literature.”

That hardly begins to appreciate the contributions Cota-Cárdenas made to Chicano culture, including becoming the first professor at Arizona State University to develop a Chicano literature class.

She also raised three children on her own, became an accomplished poet and author, and founded the publishing company Scorpion Press, which was funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and designed to publish works by bilingual, bicultural women.

Cota-Cárdenas’ life is being celebrated in a book titled “La Plonqui: The Literary Life and Work of Margarita Cota-Cárdenas,” co-edited by Vanessa Fonseca-Chavez, an associate professor of English at ASU, and Jesus Rosales, an associate professor of Spanish in the School of International Letters and Cultures.

The book was published in late September. Cota-Cárdenas’ work — and her life — will be celebrated at an event held from 3 to 5 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 9, in Ross-Blakley Hall.

ASU News talked to Fonseca-Chavez about the book and the impact Cota-Cárdenas made.

Editor's note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: For those who aren’t familiar with Cota-Cárdenas, how would you describe her contribution to Chicano life and literature?

Answer: She was one of the first Chicano writers who emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. She published two novels, "Sanctuaries of the Heart" and "Puppet: A Chicano Novella." She also produced three books of poetry. So she’s had kind of a 40-year career being one of the major literary writers in Chicano literature.

Q: Why was her Chicano literature class at ASU important?

A: What was happening is that you had all of these Chicanos who had emerged from the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and students needed to see themselves reflected in the classes they were taking. Chicano literature as a field of study did not exist before the 1960s, but Chicanos did. So you had people like Cota-Cárdenas start to develop these classes within the Spanish program within the School of International Letters and Cultures.

It was Jesus Rosales who first taught "Sanctuaries of the Heart" in a graduate class that I took on Mexican American women writers that kind of really opened my eyes to her larger contributions. I had already read "Puppet" when I was a master’s student at the University of New Mexico, and that one kind of blew my mind. It was very experimental, and that’s just the way she writes most of her books of poetry and her novels.

Q: How is her writing experimental?

A: It’s a lot of English and Spanish mixed together. For a long time in Chicano literature, you would produce Spanish with a glossary, or you would italicize it to make sure that your reading audience knew that it was Spanish. You would provide direct translations within the text, and that’s not something Margarita cares to do. So when I say she’s kind of unapologetic and experimental, she uses the language as she would use it in everyday life.

There’s not a lot of writing patterns that lend themselves to direct translations into English. Her words will flow into other words and phrases. And, again, Spanish and English are mixed constantly throughout. She’ll even make up words if the occasion calls for it. So you can’t dissect her work that easily. And I think that’s really lovely about it.

Q: In reading her Wikipedia page, she seems like a remarkable woman. She was a single mom, she thought of becoming a nun, then she was a published author and important contributor to the Chicano community. Am I reading her right?

A: You are. As part of the collection in the book, there is an interview with her where she does talk about her different career options, becoming a mom early on in her life, and then ultimately her decision to dedicate her life to poetry and to writing. What’s interesting is that within just Chicano literature writ large, there is this expression of limited options for females. You would get married or become a nun. Those were essentially the two options available to you. So we really like these Chicano writers who chose a different path for themselves. And what a tremendous impact they’ve had.

Q: Did Cota-Cárdenas open the door for other female Chicano writers?

A: I would say so. Chicano culture is very patriarchal, just generally speaking. But she doesn’t have a filter in her writing. She directly calls people out. And she doesn’t apologize for calling it what it is. I think that’s very brave, especially during her time period. I think it gives permission for scholars like myself to be the same way. If we see these injustices, even within our own families or other cultures kind of perpetuating in our own communities, we can say, “Hey, you have to cut that out.”

Q: So, she was a trailblazer.

A: Absolutely.

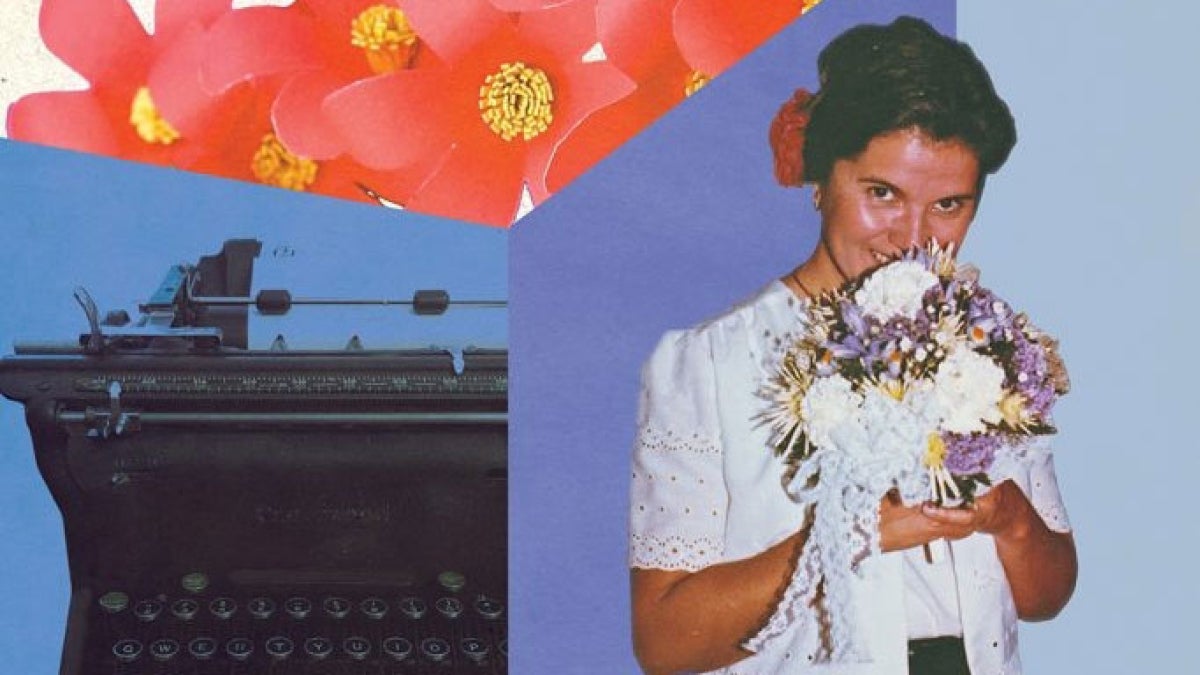

Top photo: Margarita Cota-Cárdenas featured on the book cover for "La Plonqui."

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…