Webb Telescope's gravitational lens reveals distant objects behind 'El Gordo' galaxy cluster

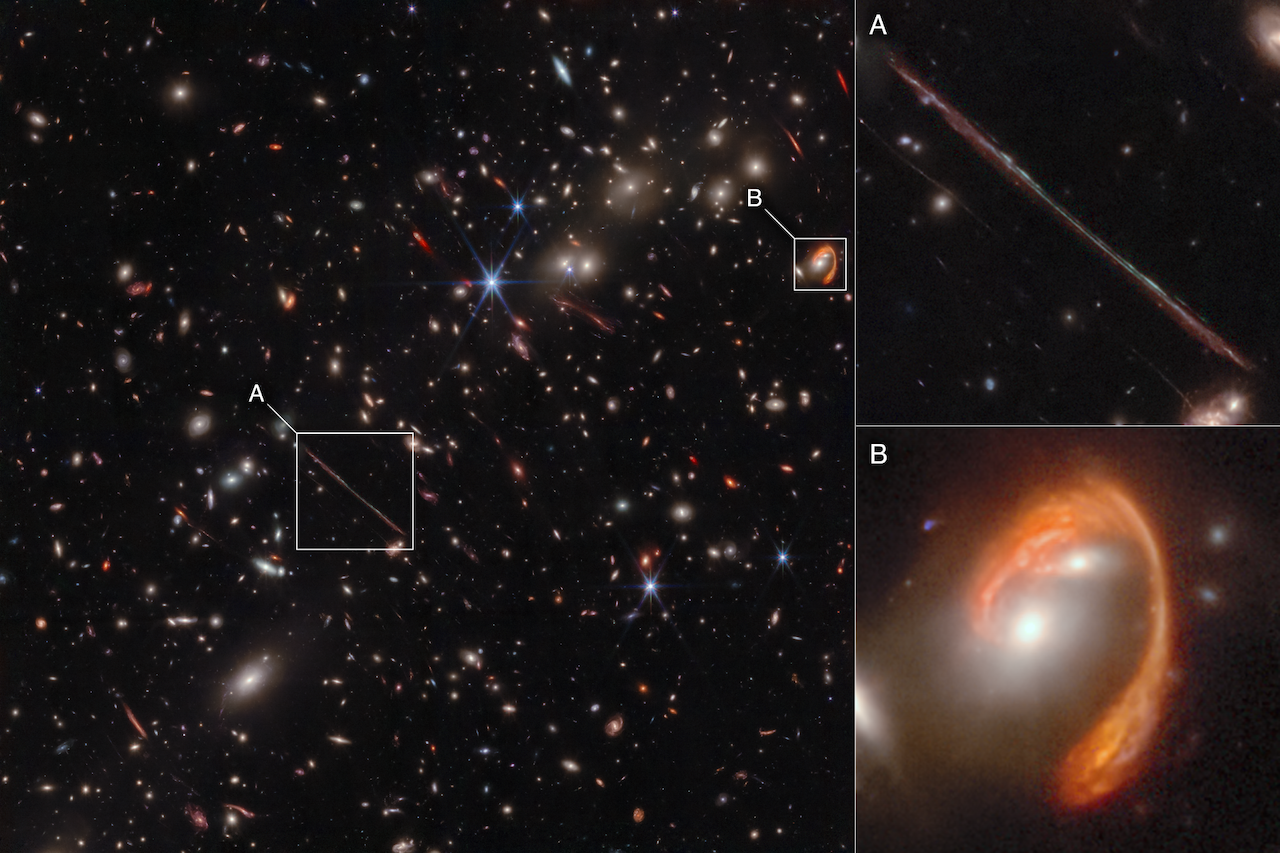

Webb’s infrared image of the galaxy cluster El Gordo reveals hundreds of galaxies, some never before seen at this level of detail. El Gordo acts as a gravitational lens, distorting and magnifying the light from distant background galaxies. Two of the most prominent features in the image include "The Thin One," located just below and left of the image center, and "The Fishhook," a red swoosh at upper right. Both are lensed background galaxies.

The NASA James Webb Space Telescope is the largest, most powerful and complex telescope in space. By observing through nature's natural lens, Webb has captured a new image of distant and dusty objects never seen before, which are amplified behind the most massive and distant galaxy cluster known as “El Gordo,” or "The Fat One."

The recent infrared image taken by JWST displays a variety of unusual, distorted background galaxies that were only hinted at in previous Hubble images.

El Gordo is a cluster of hundreds of galaxies that existed when the universe was 6.2 billion years old, making it a “cosmic teenager.” It’s the most massive cluster known to exist at that time.

Four papers describing the newly discovered distant and dusty objects, which have been published in the Astrophysical Journal or Astronomy & Astrophysics Journal, are the result of an international collaboration of researchers from Arizona State University, the Space Telescope Science Institute, the University of Arizona and the Instituto de Física de Cantabria in Spain.

The team of astronomers targeted a galaxy cluster known as “El Gordo” because it acts as a natural, cosmic magnifying glass through a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing. Its powerful gravity bends and distorts the light of objects lying behind it, similar to a lens in eyeglasses.

“Gravitational lensing was predicted by Albert Einstein more than 100 years ago. In the El Gordo cluster, we see the power of gravitational lensing in action,” said Rogier Windhorst of Arizona State University, principal investigator of the Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing Science (PEARLS) program. “The PEARLS images of El Gordo are out-of-this-world beautiful. And they have shown us how Webb can unlock Einstein's treasure chest.”

Discovered in 2012 by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope and studied by various telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the El Gordo cluster JWST distant universe image is one of the crown jewels for the PEARLS program.

Clusters of galaxies and gravity bending

The first observation in these new images is that a lot of galaxies that were next to invisible or truly invisible to Hubble are quite bright in the images taken by JWST. And that is because JWST is sensitive to near infrared light from the stars of those galaxies. And Hubble could not do that.

These galaxies are so far away that the light emitted by stars has been stretched to look redder.

Lead author on a second paper, Patrick Kamieneski, exploration postdoctoral fellow at ASU, said, “Galaxies ... that are forming stars within dense shrouds of dust would have been previously missed by even Hubble. Gravitational lensing provides an extra advantage, by warping and magnifying the galaxy to offer us an intimate view of star formation in the distant universe.”

"It's no longer in the optical where Hubble excels," said Rolf Jansen, a research scientist at ASU’s School Of Earth and Space Exploration. "The light is stretched to the point that you need to have a near infrared or a mid-infrared camera to pick up that light. And the images that we get from JWST show that there are stars everywhere.”

And not just stars in the galaxies themselves, but scientists are able to view the stellar streams, the remnants of interactions between galaxies in the busy cluster environment.

The team had some inkling that stellar streams were present, from numerical simulation and really deep ground-based imaging. But they had no idea that it is going on everywhere and that it is detectable and visible.

“Lensing by El Gordo boosts the brightness and magnifies the sizes of distant galaxies. This lensing effect provides a unique window into the distant universe,” said Brenda Frye of the University of Arizona. Frye is co-lead of the PEARLS-Clusters branch of the Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing Science (PEARLS) team and lead author of one of four papers analyzing the El Gordo observations.

'The Fishhook'

With high precision, the distant objects detailed in the El Gordo image are literally out of this world.

The clusters of galaxies modify the images of distant objects — spaghettified into strings or pencil-like objects. One strange-looking object is called “El Anzuelo" (The Fishhook), nicknamed by one of Frye's students and studied by Kamieneski.

A lensed view of the El Anzuelo galaxy becomes undistorted.

The light from El Anzuelo took 10.6 billion years to reach Earth. Its distinctive red color is due to a combination of reddening from dust within the galaxy itself and cosmological redshift due to its extreme distance.

By correcting for the distortions created by lensing, the team was able to determine that the background galaxy is disk-shaped but only 26,000 light-years in diameter — about one-fourth the size of the Milky Way. They also were able to study the galaxy’s star formation history, finding that star formation was already rapidly declining in the galaxy’s center, a process known as quenching, in which a galaxy runs out of gas to make new stars.

“We were able to carefully dissect the shroud of dust that envelops the galaxy center where stars are actively forming," Kamieneski said. "Now, with Webb, we can peer through this thick curtain of dust with ease, allowing us to see firsthand the assembly of galaxies from the inside out."

'The Thin One'

Returning to the Webb image, another prominent feature is a long, pencil-thin line at left of center. Known as “La Flaca" (The Thin One), it is another lensed background galaxy whose light also took nearly 11 billion years to reach Earth. When the researchers examined another stretched galaxy, they found three images of a single red giant star that they nicknamed Quyllur, which is the Quechua term for star.

Previously, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope had found other lensed stars (such as Earendel), but these were all blue supergiants. Quyllur is the first individual red giant star observed beyond 1 billion light-years from Earth. Such stars at high redshift are only visible using the infrared filters and sensitivity of Webb.

“It's almost impossible to see lensed red giant stars unless you go into the infrared. This is the first one we’ve found with Webb, but we expect there will be many more to come,” said Jose Diego of the Instituto de Física de Cantabria in Spain, lead author of a third paper on El Gordo.

Webb’s infrared image of the galaxy cluster El Gordo reveals hundreds of galaxies, some never before seen at this level of detail. El Gordo acts as a gravitational lens, distorting and magnifying the light from distant background galaxies. Two of the most prominent features in the image include "The Thin One," highlighted in box A, and "The Fishhook," a red swoosh highlighted in box B. Both are lensed background galaxies. The insets at right show zoomed-in views of both objects.

Galaxy group and smudges

Other objects within the Webb image, while less prominent, are equally interesting scientifically.

For example, Frye and her team (which includes nine students from high school to graduate students) identified five multiple-lensed galaxies that appear to be a baby galaxy cluster forming about 12.1 billion years ago. There are another dozen candidate galaxies that may also be part of this very distant proto-cluster.

“While additional data are required to confirm that there are 17 members of this proto-cluster, we may be witnessing a new galaxy cluster forming right before our eyes, just over a billion years after the Big Bang,” Frye said.

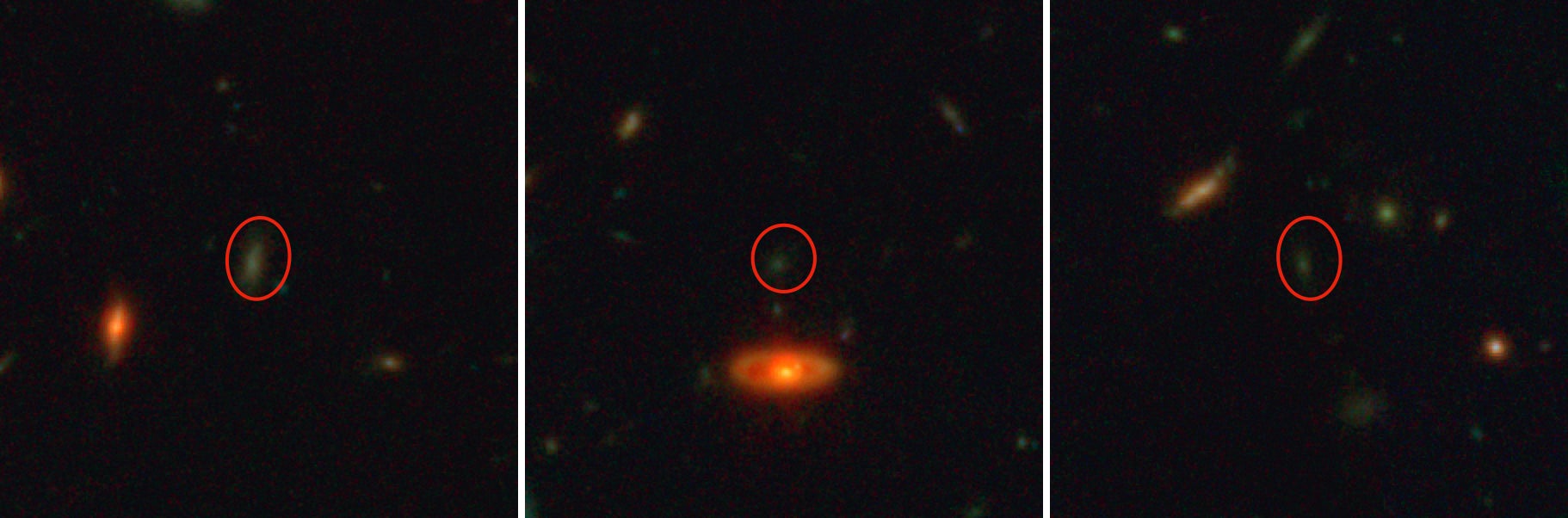

A final paper examines very faint, smudge-like galaxies known as ultra-diffuse galaxies. As their name suggests, these objects, which are scattered throughout the El Gordo cluster, have their stars widely spread out across space. The team identified some of the most distant ultra-diffuse galaxies ever observed, whose light traveled 7.2 billion years to reach us.

“We examined whether the properties of these galaxies are any different than the ultra-diffuse galaxies we see in the local universe, and we do actually see some differences. In particular, they are bluer, younger, and more extended and more evenly distributed throughout the cluster. This suggests that living in the cluster environment for the past 7 billion years has had a significant effect on these galaxies,” said Timothy Carleton of ASU, lead author on the fourth paper.

Three ultra-diffuse galaxies (leftovers of galaxy formation) in the El Gordo cluster observed with JWST.

The paper by Frye et al. has been published in the Astrophysical Journal. The paper by Kamieneski et al. has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. The paper by Diego et al. has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. The paper by Carleton et al. has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

Image credits: Science: NASA, ESA, CSA, Jose M. Diego (IFCA), Brenda Frye (University of Arizona), Patrick Kamieneski (ASU), Tim Carleton (ASU), Rogier Windhorst (ASU); Animation Image Processing: Patrick Kamieneski (ASU), Jake Summers (ASU), Jordan C. J. D'Silva (UWA), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI), Aaron Robotham (UWA), Rogier Windhorst (ASU)

This release was written by the Space Telescope Science Institute press team with contributions from Kim Baptista of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

More Science and technology

ASU professor honored with prestigious award for being a cybersecurity trailblazer

At first, he thought it was a drill.On Sept. 11, 2001, Gail-Joon Ahn sat in a conference room in Fort Meade, Maryland.…

Training stellar students to secure semiconductors

In the wetlands of King’s Bay, Georgia, the sail of a nuclear-powered Trident II Submarine laden with sophisticated computer…

ASU startup Crystal Sonic wins Natcast pitch competition

Crystal Sonic, an Arizona State University startup, won first place and $25,000 at the 2024 Natcast Startup Pitch Competition at…