Disruption 2.0: Event focuses on dilemmas around AI in new creativity landscape

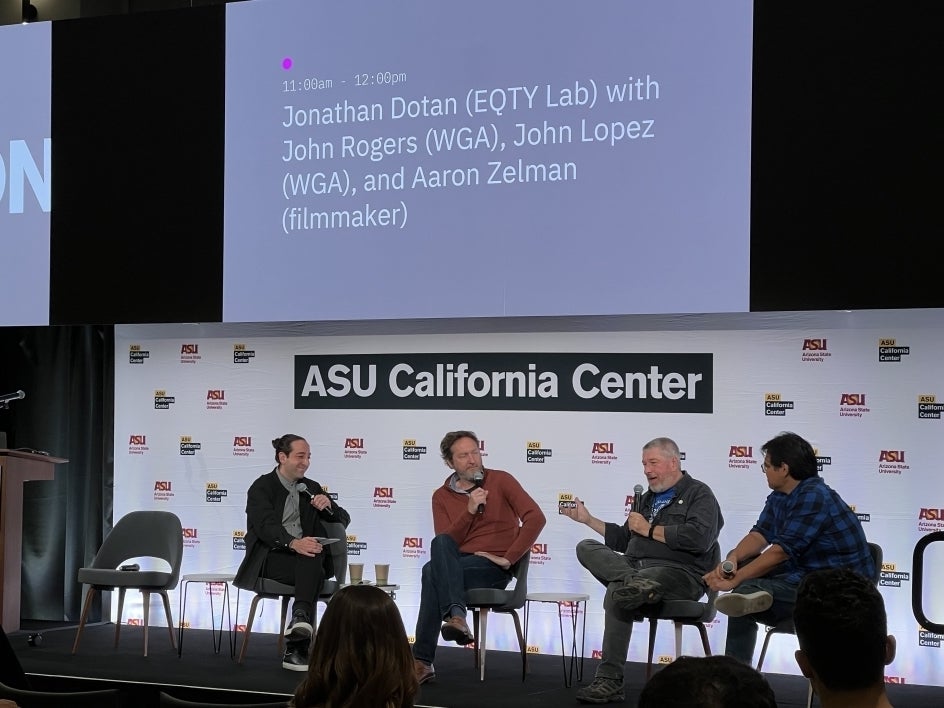

Jonathan Dotan leads the discussion about generative AI during the Disruption 2.0 event at the ASU California Center. Photo by Charles Anderson

Writers, filmmakers, lawyers and thought leaders met in June at the ASU California Center in Los Angeles to try to answer some of the critical dilemmas posed by the rise of generative artificial intelligence and its impacts in the entertainment industry.

Disruption 2.0, a collaboration between ASU’s narrative and emerging media master's program, Creative Commons and Eqty Lab, was held at the historic Herald Examiner building.

“As more countries are beginning to draft legislation around AI and the Writers Guild of America strikes, partially around the threat that AI can pose, now is the time for substantive dialogue and conversation around creator rights directly impacted by AI and its secondary effects,” EQTY Lab founder Jonathan Dotan said.

Dotan said that lessons on the current rise of AI could be drawn from history — particularly the impact of loom technology on the textile industry during the first Industrial Revolution.

“The arrival of textiles into Great Britain brought a huge amount of social change. … The technology of the loom was the forebear for a huge amount of social change that spanned for centuries to come," Dotan said.

In the 17th century, workers feared they would lose their jobs to the technology; however, at that time organized labor was illegal. That fear was also about the distribution of fair profit — a thread that continues today through the writers’ strikes.

“Again, we are responding to change and figuring out how to use technology,” Dotan said.

Dotan described AI as a system of applied statistics that brings in vast amounts of data to create answers based on probabilities: “As it amasses more data … it is able to complete statistically better answers.”

Due to this, he said AI was not sentient. Instead, he described it as an “overconfident teenager” that “knows everything and knows nothing."

Its uses are vast — from language models like ChatGPT, which was trained on large parts of the internet, to Midjourney, which is able to create original art in seconds.

But these uses raise the need to protect the rights of artists for the works that AI might draw from. While one option would be shutting down the open-source nature of the models, that doesn't seem feasible.

“If we shut it down then that might be the end of the open internet as we know it,” Dotan said. “The risk is that we overcorrect. … Think about how the cathedrals of stone gave way to the printing press, which created a whole universe of media and creativity.”

Dotan said that creators needed “a better story” to tell about their response to AI: “We have sufficient funds and technology to address some of these problems. We need new tools and processes. It’s time to create.”

(From left) EQTY Lab founder Jonathan Dotan leads a panel discussion at ASU California Center about the impact of generative AI on the film industry with filmmaker Aaron Zelman and Writers Guild of America members John Rogers and John Lopez. Photo by Charles Anderson

Dotan then led a panel discussion with writers about the industry's challenges and opportunities from AI, which was particularly prescient as the WGA writers’ strike entered its seventh week.

As part of the strike, WGA is requesting that the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) ban the use of AI for writing and rewriting any source material, as well as its use as a source material of its own, and that no AI material be trained on WGA writers' work.

John Rogers from the WGA said concerns about plagiarism were real — even if it was hard to track down the original wrongdoing.

“We do it with money, we call it money laundering; and it's still a crime and you chase it down," Rogers said.

Filmmaker Aaron Zelman cut his teeth working on "Law and Order," but said people told him the formulaic show would be easy for AI to write. He likened that notion to when he wrote his first episode.

“After that, I ran into someone at the coffee shop, and they said that the dialogue wasn’t quite there. Maybe that’s what an AI 'Law and Order' would look like. ... Everyone on the show would say it's too facile, too rote. But this is an exponential curve here of learning that is happening.”

Zelman added that one of the biggest fears about AI was not that it was artificially intelligent but that it was artificially “creative,” which “spooked us."

John Lopez of the WGA said there was a creative process that might be lost if writers or studios looked increasingly to AI to do the job.

“I got to learn as a writer as I wrote crappy box office reports. We have automated one of the most valuable parts of being human, which is learning," Lopez said.

When Zelman asked ChatGPT how to become a better writer, it told him that it could make him more efficient.

“What if I don’t want the process to be more efficient? I’m looking for a creative process," Zelman said. "In that first draft, you discover something different that you never thought of and that becomes the thing.”

Rogers said mistakes are style.

“They might suck right now, but when you shine them up, they will be the things that make you great. You have to give people a chance to fail, and if you don’t it won’t be original or interesting.”

The Disruption 2.0 event also held panels on music and art and an open conversation with the general counsel for OpenAI.

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive —…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that…