Editor’s note: This story is featured in the 2023 year in review.

What exactly makes for a fit Fido? And how does a dog’s environment factor into their dog years?

The largest survey and data compilation of its kind, which includes more than 21,000 owners, has revealed the social determinants that may be tied to healthier aging for pet dogs. Among them, the dog’s social support network proved to have the greatest influence on better health outcomes.

“People love their dogs,” said Noah Snyder-Mackler, assistant professor in Arizona State University's School of Life Sciences. “But what people may not know, is that this love and care, combined with their relatively shorter lifespans, make our companion dogs a great model for studying how and when aspects of the social and physical environment may alter aging, health and survival.”

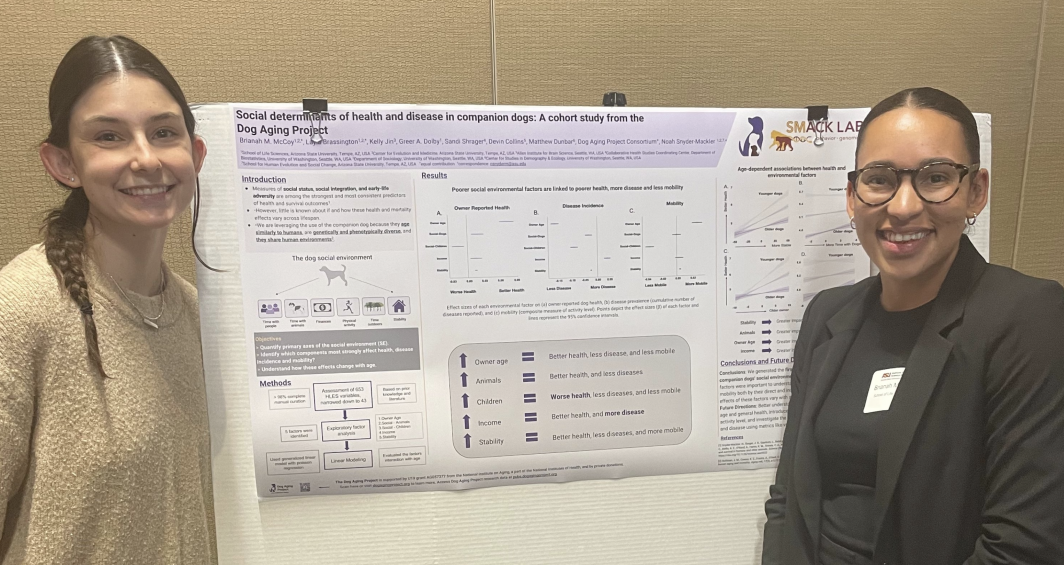

Led by Snyder-Mackler, PhD student Bri McCoy and graduate student Layla Brassington, the research team drew on the large survey that asked each owner questions about themselves and their pup — ranging from physical activity, environment, dog behavior, diet, medications and preventatives, health status, and owner demographics.

Using these questions, they identified key factors — neighborhood stability, total household income, social time with adults and children, social time with animals and owner age — that helped explained the makeup of a dog's social environment and were associated with dog well-being.

The ASU team found that the dog’s lived and built environment predicted their health, disease diagnoses and physical mobility — even after controlling for the dog’s age and weight.

More specifically, financial and household adversity was linked to poorer health and reduced physical mobility while more social companionship with humans and other dogs was associated with better health. These effects of each environmental component were not equal. The effect of social support was five times stronger than financial factors.

“This does show that, like many social animals – including humans – having more social companions can be really important for the dog’s health,” McCoy said.

ASU graduate student Layla Brassington (left) and PhD student Bri McCoy helped carry out a comprehensive analysis of a detailed survey of dog owners, covering 21,410 dogs. The study attempted to find key social aspects for healthy lifestyles to help explore the science behind dog years in a large, community-science endeavor called the Dog Aging Project. Photo by Noah Snyder-Mackler

Among the more surprising results: a negative association of the number of children in the household and dog health; and that dogs from higher income households were diagnosed with more diseases.

“We found that time with children actually had a detrimental effect on dog health,” Brassington said. “The more children or time that owners dedicate to their children, likely leads to less time with their furry children.”

“You can think of it as a resource allocation issue, rather than kids being bad for dogs,” McCoy said.

The second surprising finding points to the role that money plays in the opportunities for disease diagnosis. Dogs from wealthier households have better access to medical care — including more frequent vet visits and additional testing — leading to more diagnoses.

Their results remained largely consistent when accounting for health and diseases differences between purebred and mixed-breed dogs, as well as among specific breeds.

One important caveat to note on the data is due to the nature of surveys: Since these are owner-reported, there may be some error, bias and/or misinterpretation of survey questions.

The detailed survey came from the Dog Aging Project, a community-science endeavor led by the Schools of Medicine at University of Washington and Texas A&M that includes more than a dozen member institutions — ASU among them — around the nation. The main goal of the Dog Aging Project is to understand how genes, lifestyle and the environment influence aging and disease outcomes. More than 45,000 dogs are now enrolled in the project across the U.S.

“This study illustrates the incredibly broad reach of the Dog Aging Project,” said Daniel Promislow, project co-director and principal investigator. “Here, we see how dogs can help us to better understand how the environment around us influences health, and the many ways in which dogs mirror the human experience. Just as with people, dogs in lower-resource environments are more likely to have health challenges.

"Thanks to the richness of the data the Dog Aging Project is collecting, follow-up studies will have the potential to help us understand how and why environmental factors affect health in dogs.”

The Dog Aging Project aims to better understand healthier aging for people’s beloved canine companions. More than 45,000 dogs of all breeds and sizes have been enrolled in the study. Image courtesy Dog Aging Project

Their next steps will begin to explore if there are any links between the survey and underlying physiology.

“We now want to understand how these external factors are getting under the skin to affect the dog’s health," Snyder-Mackler said. "How is the environment altering their bodies and cells?"

A subset of about 1,000 of the dogs are part of a more focused cohort. Snyder-Mackler and his collaborators will collect blood and other biological samples over time to advance their research.

“In future research, we will look at electronic veterinary medical records, molecular and immunological measures, and at-home physical tests to generate more accurate measures of health and frailty in the companion dog,” Snyder-Mackler said.

“But the take-home message is: Having a good network, having a good social connectedness is good for the dogs that are living with us,” McCoy said. “But the structure and equities that are in our society also have a detrimental effect on our companion animals as well. And they are not the ones thinking about their next paycheck or their health care.”

And what is good for dogs may just echo what helps people live healthier lives.

“Overall, our study provides further evidence for the strong link between the social environment and health outcomes that reflects what is known for humans,” Snyder-Mackler, said. “We need to focus more attention to the role of the social environment on health and disease, and continued investigation of how each environmental factor can contribute to more years of healthy living ... in both companion dogs and humans.”

The study was published in the advanced online early edition of the journal Evolution, Medicine & Public Health.

Top photo: Two dogs who were being trained as part of Sparky's Service Dogs program hang out on Hayden Lawn on ASU's Tempe campus in 2016. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Science and technology

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking risks, having a hard time resisting temptation, difficulty getting…