Open your passport and take a look. What do you see?

Your picture. Stamps from countries you’ve traveled to. Perhaps the expiration date and the country of origin.

Patrick Bixby sees all those things too. But he also thinks about the stories the passport reveals.

“It’s a document that tells stories in a way that many other kinds of historical documents don’t,” said Bixby, an associate professor of English in the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, “because it comes along with someone as they travel, and travel is generative of stories. It tells us where someone went often, it tells us why they went there, and it tells us where they weren’t able to go. Those things become very interesting if you look closely at them.”

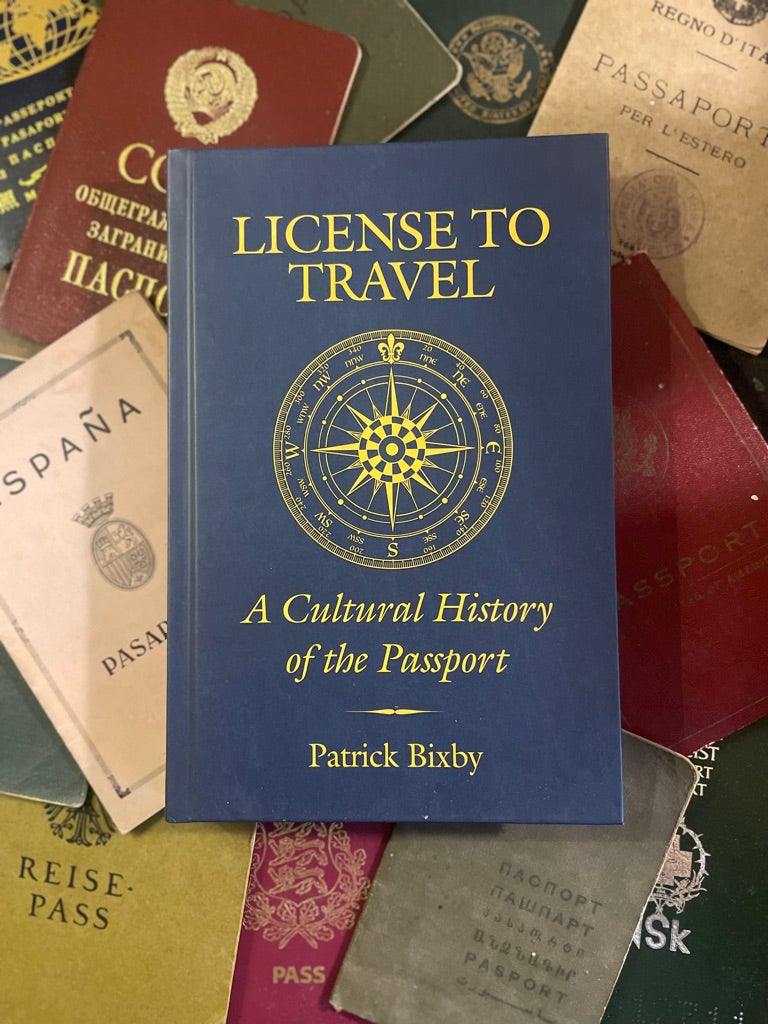

Bixby has written a book on the cultural history of passports titled “License to Travel: A Cultural History of the Passport” that will be released Oct. 25.

The book examines the passports/travel documents of artists, intellectuals, ancient messengers — as far back as pharaonic Egypt — and modern migrants to see how the document reflects larger issues such as citizenship, state authority and identity.

“It seems like a mundane object, this piece of paperwork,” Bixby said. “Most people don’t give it too much thought. So, I liked the idea of taking this more or less everyday object that people don’t think about too much … and looking more closely at it to unearth all of these stories.”

ASU News spoke with Bixby about his book.

Note: The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Question: What made you interested in this topic in the first place?

Answer: I’ve had my own experience with passports, traveling international for 30 years. Some of those experiences have been pleasurable, seeing different parts of the world, meeting interesting people, all the things travel has to offer. But I’ve also had my fair share of certain anxieties associated with passports, like having them lost or stolen, or even that moment when you’re getting ready to go on a trip, you’re heading out the door to the airport, and you’re like, “Where is this thing?" Searching for it in your bag and having that moment of panic because everything depends on it, right? That little book really controls where we are, where we can go and where we can’t.

And then my day job, as it were, is a scholar of modernist literature. The modern passport regime that we live under now grew up out of the first World War. Most of the standards that are adhered to in the international community were first codified right after the war in a series of conferences. So, the first generation of people to travel under the modern passport regime included writers and artists and others who I study. I studied their work, and I began to see ways that the passport regime and their dependence on passports shaped their emotions, their imaginations and their work. And that’s where this idea of a cultural history came about.

Q: What’s the primary storyline of the book?

A: The main idea, which is a fairly obvious one, is that the passport is a place where the person and the political come together. They are our documents in a sense … but on the other hand they are a document that implicates us in international relations. This became very evident during the pandemic when all of a sudden there were all sorts of new visa requirements and parts of Europe were shut off to U.S. passport holders. So, these little books connect us as individuals to these larger structures and historical concerns.

Q: What is the cultural history of the passport?

A: One of the things that I was very surprised to find is that there were passport-like objects all the way back to pharaonic Egypt. These little clay tablets were carried by messengers that allowed them to pass through different territories. That’s more than 3,000 years ago. In the Han dynasty in China, they had a very intricate set of controls to regulate traffic on the Silk Road (a network of routes used by traders). So, you can go all the way back to deep history and find all sorts of precursors and the way that those documents gather significance for individuals and for these larger historical concerns about the nation-state and sovereignty and so forth.

Q: Are those some of the narratives explored in the book?

A: Yes. One of my favorite stories in the book involves Frederick Douglass, the formerly enslaved person who became a human rights advocate and an abolitionist hero. He made his flight from slavery by using some borrowed (freedom papers) that allowed him to board a train in disguise. He traveled without a passport for a number of years going to the United Kingdom to advocate for the abolitionist cause. But he was denied a U.S. passport when he requested one because of the Dred Scott decision, which denied citizenship to enslaved, formerly enslaved and free African Americans. So, that document became an emblem of the citizenship that he was being denied. After the repeal of the Dred Scott decision, Douglass got his very first passport, and that document is in the national archives. And then he goes off on his wonderful trip (with his second wife), which he had sort of dreamed about his entire life, even when he was enslaved. He writes of having this kind of wanderlust, of wanting to see the world. It’s very poignant because, of course, all that was closed off to him.

Q: Are there any other historical figures you researched that intrigued you?

A: One of the stories I tell at the very center of the books is about James Joyce, the Irish novelist who was kind of in self-exile. He left Ireland because he found the social mores and the artistic horizons just too limiting for him. So, he went off to Trieste in the Austro-Hungarian empire, taught English there and worked on his early works and tried to raise a family on little money. But then the first World War starts and he’s compelled to leave there because he’s what was then a British citizen and was no longer wanted in that part of the world. So, he has to go off to Switzerland, a neutral country, where he finds a new sort of haven where he can do his work. So, he gets a passport, and the passport sort of tracks his movements during that period from the war to the early 1920s when he relocates again in Paris. That’s the same period that he was writing "Ulysses," his iconic novel. So, that little piece of paper now provides a record of his movements while he’s writing one of the great works of literature in the 20th century.

Q: So, you’re using these individual stories to show how passports shape narratives of some of these issues.

A: Exactly. That’s what I think makes it a good read and certainly made it a lot of fun to write. I’m writing stories about individuals, their particular desires, their wants, their needs, their fears, but those are always tangled up in stories with these larger historical concerns.

Q: When you talk in the book about government authority and the rise of the nation-state, what is the passport’s place in that structure?

A: Well, passports were one of the forms for documenting citizenship. When nation-states became more clearly drawn in their borders, beginning in the late 18th century and increasingly through the 19th and up to the early 20th century and the first World War, keeping people in the right place was an important concern. You want to collect taxes, and there’s worries about sabotage, espionage and so forth. So, the passport was an important tool to track and register a population. It becomes one of a number of government methods to say, “OK, this person has a right to be here and they have a right to go there. That person doesn’t have a right to be here." This is mostly in the European context, so as the map of Europe evolves the passport plays an important role in regulating the populations across that map.

Q: I’m curious. After doing all the research for this book, do you look at your passport differently?

A: I do. If you look at the language of the U.S. passport and the kinds of demands that it makes of other governments, it basically says take good care of my citizen. Those kinds of demands or commands even are on clay tablets in ancient Greece. So, the language in the passport and the way it asserts the rights and privileges of the passport holder is rather remarkable because, after all, it’s just words, but they have a lot of power.

Top photo by Ekaterina Belinskaya via Pexels.com

More Arts, humanities and education

Professor's acoustic research repurposed into relaxing listening sessions for all

Garth Paine, an expert in acoustic ecology, has spent years traveling the world to collect specialized audio recordings.He’s been to Costa Rica and to Ecuador as part of his research into innovative…

Filmmaker Spike Lee’s storytelling skills captivate audience at ASU event

Legendary filmmaker Spike Lee was this year’s distinguished speaker for the Delivering Democracy 2025 dialogue — a free event organized by Arizona State University’s Center for the Study of…

Grammy-winning producer Timbaland to headline ASU music industry conference

The Arizona State University Popular Music program’s Music Industry Career Conference is set to provide students with exposure to exciting career opportunities, music professionals and industry…