The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently reporting 4,638 cases of monkeypox in the United States, with 41 cases in Arizona.*

According to the CDC, “monkeypox is a rare disease caused by infection with the monkeypox virus. Monkeypox virus is part of the same family of viruses as variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox. Monkeypox symptoms are similar to smallpox symptoms, but milder, and monkeypox is rarely fatal. Monkeypox is not related to chickenpox.”

Megan Jehn is an infectious disease epidemiologist and associate professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University.

Here, Jehn clears up some misinformation about monkeypox and answers some other questions about the disease.

Megan Jehn

Question: What does an epidemiologist, like yourself, do? Why is your job important in the role of global health?

Answer: Epidemiologists primarily search for the cause of disease, identify people who are at risk, determine how to control or stop the spread or prevent it from happening again.

Q: What is monkeypox? Where did monkeypox originate?

A: Monkeypox is a rare disease caused by infection with the monkeypox virus. It leads to a painful rash and flu-like symptoms. This virus belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus, a family that also includes the variola virus, which causes smallpox. It was first discovered in Denmark in 1958 in captive primates used for research. The first human case of monkeypox was documented in 1970 in a 9-month-old child in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite its name, the natural reservoir is not actually monkeys. In nature, the virus is most often found in rodents and squirrels.There are two known strains of the virus — a west African and a central African (Congo Basin) strain.The strain circulating in the current U.S. outbreak is the west African strain, which is less severe.

Q: How is monkeypox both similar and different from other viral diseases we are more familiar with (e.g., chicken pox, hand-foot-mouth, etc.)?

A: There are certain similarities. People who are infected with monkeypox often develop fever, muscle aches and fatigue, similar to other viral illnesses. The rash caused by monkeypox can also resemble those caused by measles, chickenpox and some STIs, making early diagnosis difficult. However, monkeypox is different from other viruses in that it is an orthopoxvirus, it is rare and generally not considered highly contagious. Monkeypox virus enters the body via broken skin, respiratory tract and mucus membrane, while chickenpox virus enters mainly via respiratory tracts.

Q: Why are we seeing monkeypox in countries where the virus is not historically found? Is this a more virulent strain, or what is aiding to its spread?

A: Monkeypox cases most often arise from animal-to-human transmission. In years past, we have seen small localized outbreaks of monkeypox associated with travel or imported animals. The current situation is quite different.

The current outbreak is the largest ever in the U.S. and globally, and it is the first time that we have seen substantial local transmission in non-endemic countries. It does not appear that the current outbreak was caused by an animal-to-human crossover event. The more likely scenario is that there were multiple introductions into sexual networks, which led to superspreader events through an optimal combination of biology, contact patterns, travel and exposure routes, triggering rapid worldwide spread. There is also some recent genetic sequencing data which suggests that the current strain diverged from a strain that caused the 2018–19 Nigerian outbreak and has mutated to become more transmissible.

Q: How is monkeypox transmitted? What can average people do to help protect themselves? Can this spread through clothing or other soft surfaces?

A: Monkeypox is spread through close skin-to-skin contact, breathing respiratory droplets, direct contact with lesions and contact with contaminated surfaces. Although most current cases have been linked to sexual contact among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, monkeypox can be a risk to anyone, regardless of sexual orientation or sex/gender of sexual partners. Individuals with lesions can shed virus onto bedsheets, towels or other linens that can spread the virus to others.

It is important to note that monkeypox has historically not been considered easy to transmit from person to person. For prevention, avoid close, skin-to-skin contact with people who have a rash with symptoms consistent with monkeypox or who have been recently diagnosed with monkeypox. Vaccination is recommended for people who have been exposed to monkeypox and people who are at higher risk of being exposed to monkeypox.

Q: Many people believe this to be an STI (sexually transmitted infection). Is this true? Why is there this assumption, and why is that a harmful assumption?

A: No, monkeypox is not an STI. It is important to use language around disease transmission and risk accurately. It is spreading like an STI right now, but it is not an STI. It is a contact-based disease spread through skin-to-skin, fluids and soiled materials so anyone can get it. But just because anyone can get it, doesn’t mean that everyone is equally likely to get it.

Messaging that this disease is a STI that only affects gay men reinforces homophobic stereotypes and perpetuates stigma. I think this debate is also a unfortunate reminder that sex, and especially sex between men, is heavily stigmatized and that many people still view STIs through a moral lens — the kind of person who gets them — versus a medical lens — a type of illness.

Stigma will discourage people from getting tested, thus continuing to spread the disease. We need to prioritize resources and mitigate spread in communities of greatest known risk, while building broader awareness that monkeypox does not discriminate, but people do.

Q: What are your thoughts as to why the World Health Organization has declared monkeypox a “public health emergency of international concern,” but the U.S. is still debating whether to do so?

A: I would expect that we will see the U.S. declare a PHE (public health emergency) in the coming days.

Q: What makes something a public health emergency? How is that the same or different from other terminology we are now familiar with — such as endemic, pandemic, etc.?

A: A public health emergency declaration in the U.S. is made by the Department of Health and Human Services if a severe disease or disorder has become, or threatens to become, a significant threat to citizens. It unlocks funds and resources for things like purchasing medical supplies for the strategic national stockpile and vaccine development and procurement. It also serves as a call to action for states and counties to assess their own risk and mount the appropriate local public health response.

Q: How do we fight this virus?

A: To be clear, monkeypox is an awful illness. It can lead to debilitating pain, disfigurement and unjust social stigma, and we need to do everything that we can to stop the outbreak. We need to immediately focus on getting limited resources like testing and vaccines to the people who need them most to prevent needless suffering and slow the spread. We also need to increase access to treatment, launch new research efforts to address key science gaps, and improve community response and outreach.

Q: Anything else you would like to add?

A: This is an evolving situation and there is still a lot that we don't know about the current outbreak. The chain of transmission of many of the new cases has not been identified. Given that testing is increasing, and the fact that monkeypox has a long incubation period, we are likely to see a spike in infections emerge within the coming days and weeks. We need an equitable global response with vaccines directed to countries that have borne the brunt of the disease burden and deaths.

*Numbers from the time of reporting.

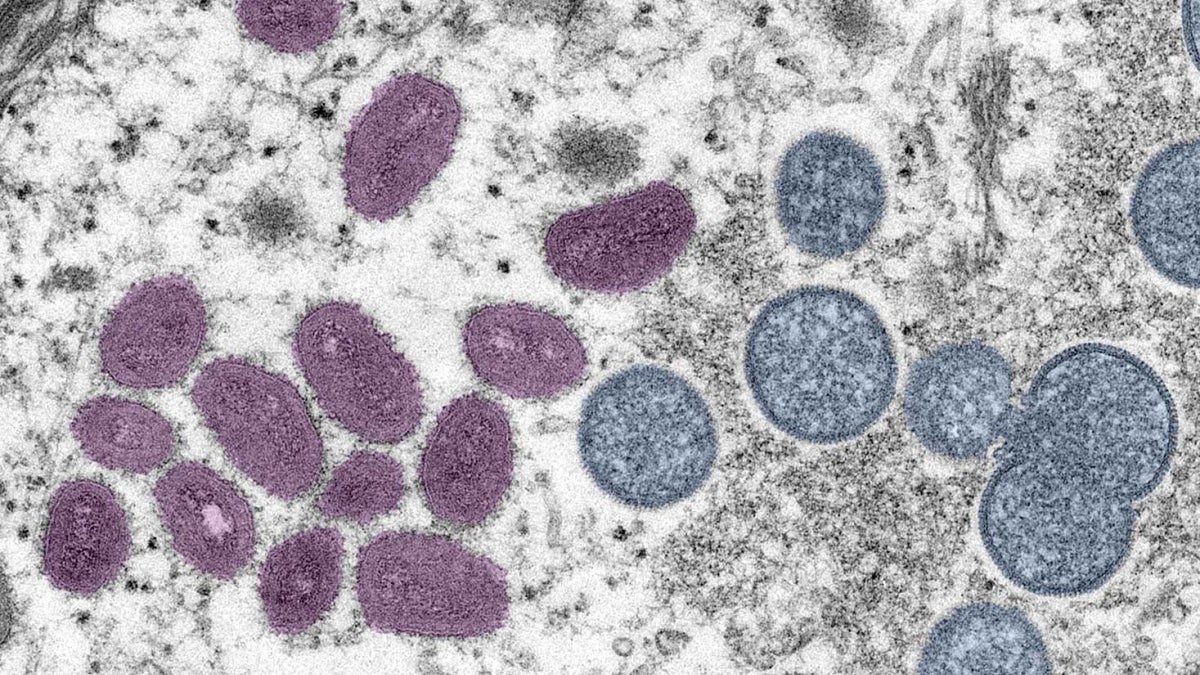

Top photo: Digitally colorized electron microscopic image depicting monkeypox virus particles. Photo courtesy of CDC

More Science and technology

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…