The offices were frozen in time.

A calendar from March 2020 highlighted St. Patrick’s Day. Balloons lay deflated in a cubicle. Half-filled water bottles and coffee cups remained on desks.

As James Burns, executive director of the Western Spirit Museum in Scottsdale, and three Arizona State University students – Jenna Bassett, Alex Fierro and Gabriel Santiago – began their treasure hunt this February at Salt River Project’s Papago Buttes Facility, they were stunned by the silence and barrenness.

“It was like a ghost town, just completely empty,” Bassett said of the SRP Information Services Building. “It was strange to see all these empty cubicles, just like an ocean of empty cubicles in a building like that, where there’s a lot of life.”

The treasure was there, though. They just had to find it.

They opened every door and looked in every room. They were often alone, except for the occasional custodian making sure the building stayed clean, ready for its inhabitants to return, and the security guard who opened locked doors.

“It was a little creepy going into this six-story building that had not been occupied since March of 2020,” Burns said.

“I remember Gabriel pointing out that it’s almost like we were witnessing history itself, in its rawest form,” Fierro added.

The search took six days. A “scavenger hunt,” Fierro called it. Eventually, they found what they were looking for: SRP’s art collection, 115 pieces in all, including sculptures, paintings and photos, many of them from Indigenous, Latino and female artists.

“Who would have thought,” Bassett said, “an electric company would have been so forward-thinking when it came to art?”

Origins of the collection

Why does SRP have an art collection?

Ileen Snoddy, a senior representative in the SRP Research Archives and Heritage Department, said the collection was purchased in 1990 to inspire a dialogue among employees. SRP also planned to have public viewings of the art, but as security measures increased in the Information Services Building – where SRP’s computers are stored — the company realized that wasn’t possible.

SRP inventoried its collection in 2003. And that’s where this story might have ended if Snoddy didn’t run into Burns at an event late last year. SRP had decided it wanted to share its art collection with the community, curating exhibits and loaning them to local museums.

“The vision was that corporate art should not just hang in your corporation,” Snoddy said.

There was just one problem. Almost 19 years had passed since the inventory had been completed. SRP needed new condition reports on the art to find out if pieces could travel, how they needed to be packaged, what type of light was needed to display them, etc.

Burns immediately had an idea.

“What would be really great,” he told Snoddy, “is to give some students are who in different museum studies and education programs at ASU an opportunity to be able to come in and learn hands-on what it’s like to curate something.”

Partnering with ASU

Burns is a graduate of the ASU Public History Program and has taught an undergraduate capstone course titled History in the Wild: Inclusion in Museums and Public History.

When SRP agreed to the student internship idea, Burns got the word out at ASU, interviews were conducted and Bassett, a PhD student in history, Fierro, finishing up his master’s degree in history, and Santiago, who will be a senior this fall majoring in secondary education, were chosen.

Alex Fierro, Gabriel Santiago and Jenna Bassett are working with SRP on organizing its art collection.

Each student brought a varied set of skills to the project, which made them, as Snoddy said, “a dream team.”

“Jenna is a strong writer and researcher,” Burns said. “Her insights and attention to detail were very helpful in maintaining precise, accurate records. Her concern for objects, the people associated with those objects and the historical record is palpable.

“(Alex) has strong reasoning and logistical skills, but also creativity and imagination – a combination not found in many people.

“Gabriel has well-honed critical thinking skills and a great imagination. He also impressed me with his passion for learning, his love of history education, and his ability to interface well with literally anyone.”

Their job was to locate and inventory the collection and conduct primary research on all the pieces.

“I think for all of us, we can all agree that studying history teaches you a certain set of skills of how to think critically, how to examine documents and translate that into solving issues,” Santiago said. “I think you could put a history person in charge of anything investigatively, and we’ll figure it out. So, I think it was a perfect match.”

Burns and the students began their quest by examining SRP’s 2003 inventory. Then the search began.

“The inventory report kind of told us which areas of the building we should expect the artwork to be in,” Fierro said. “Over time, the artwork kind of got moved around a little bit because some people would like a certain piece of art and they wanted it in front of their office, or maybe it fit better in a certain spot.

“So it was a little bit of a scavenger hunt as we went through. That’s what made it so fun.”

Highlighting diverse artists

SRP’s collection featured 80 artists, many of them from the Southwest, California and Mexico. Among them: Roberto Marquez, a Mexican-born painter whose works have been exhibited in numerous museums; Mark Klett, a photographer who is a Regents Professor in ASU’s School of Art and has his work in more than 80 museums worldwide; Emmi Whitehorse, a painter and member of the Navajo Nation; and Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, a Native American artist known for her abstract paintings and prints.

“What’s extraordinary is how far ahead of the curve SRP was in terms of collecting art created by women and artists of color,” Burns said.

The students have moved on to the second phase of the project, which includes downloading the information they gathered into SRP’s software systems, photographing each piece of work, cataloging work in other SRP buildings and recommending any re-framing that needs to be done.

Today, SRP is no longer a ghost town. Calendars have been turned. Coffee cups have been cleaned. Bassett, Fierro and Santiago, after some initial questioning, are now a welcomed part of the daily routine.

“People actually stopped and asked us who we were,” Bassett said.

Just call them SRP’s treasure hunters.

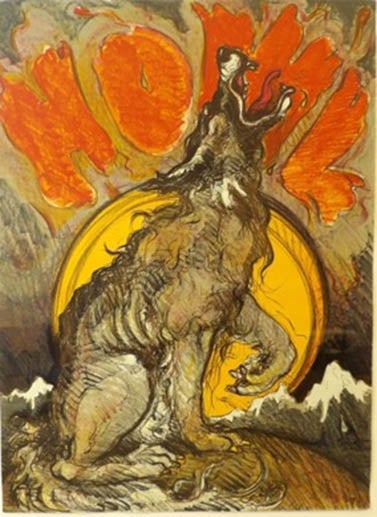

Top image: "Sleep Bouquet" by Patricia Gonzalez. Courtesy SRP

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU’s Humanities Institute announces 2024 book award winner

Arizona State University’s Humanities Institute (HI) has announced “The Long Land War: The Global Struggle for Occupancy Rights” (Yale University Press, 2022) by Jo Guldi as the 2024…

Retired admiral who spent decades in public service pursuing a degree in social work at ASU

Editor’s note: This story is part of coverage of ASU’s annual Salute to Service.Cari Thomas wore the uniform of the U.S. Coast Guard for 36 years, protecting and saving lives, serving on ships and…

Finding strength in tradition

Growing up in urban environments presents unique struggles for American Indian families. In these crowded and hectic spaces, cultural traditions can feel distant, and long-held community ties may be…