Fifty years later, we still can’t refuse the offer.

“The Godfather” officially turns a half-century on March 14, and the Francis Ford Coppola mob epic still manages to capture our imaginations five decades later. Starting this month and stretching through the spring, we’ll see celebrations, retrospectives and the debut of a dramatic miniseries called “The Offer,” based on Oscar-winning producer Albert S. Ruddy’s never-before-revealed experiences making the picture. An HBO film called “Francis and the Godfather,” directed by Barry Levinson, started pre-production in 2021.

The film has also spawned several cultural godchildren and been spoofed and parodied in film, television and commercials. Rappers like Snoop Dogg, Chris Webby, Tory Lanez and others have turned to “The Godfather” for inspiration in their songs and videos. More recently, big-budget video games and podcasts have explored the family saga through these media.

The 1972 blockbuster was the biggest film at the box office in a year that saw “Deliverance,” “Cabaret” and “The Poseidon Adventure.” It was also nominated for 11 Academy Awards and took home hardware for best picture, best screenplay and best actor. The nearly three-hour iconic motion picture revived Marlon Brando’s flagging career while minting a handful of newer stars: Al Pacino, Diane Keaton, James Caan, Robert Duvall and Talia Shire.

Before these celebrations get underway, ASU News reached out to Kevin Sandler, an associate professor in Arizona State University's Film and Media Studies programThe Film and Media Studies program is an academic unit within ASU's Department of English., to discuss “The Godfather’s” impact on cinema, pop culture and society, and why cinema-goers can’t "fuggedabout" this love letter to the mob.

Kevin Sandler

Question: You’ve been teaching a class on the films of Francis Ford Coppola at ASU since 2008. What do you find interesting about the man and his movies?

Answer: While finishing my PhD in 1999, I was offered to teach a course on the Hollywood directors John Ford and Francis Ford Coppola. At that time, Coppola and his films were still larger than life. He had yet to be eclipsed by his daughter Sofia in terms of cultural awareness and popularity as her first feature film, “The Virgin Suicides,” premiered that same year. Coppola's first two “Godfather” films and his 1979 film “Apocalypse Now” were epic in stature, a grandeur that still holds true for audiences today. Both “Godfathers” (1 and 2) won Academy Awards for best picture, while Coppola's smaller gem, “The Conversation” and “Apocalypse Now” won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1974 and 1979.

A decade later, Coppola — the person and the director — still resonated for me. Here was a man who arguably was the most famous director on the planet in the 1970s, whose name above the credits guaranteed a distinction of the utmost quality, who ended up bankrupt after the 1982 film “One from the Heart.” To crawl his way to solvency, he made disposable films like “The Cotton Club” and “The Rainmaker,” but also the arty teen pic “The Outsiders” and the arthouse picture “Rumble Fish,” only to return with the gothic horror of "Bram Stoker’s Dracula" and “The Godfather: Part III," which many consider to be an embarrassing end to the Corleone family saga. That is quite a journey, and one I wanted to investigate as a film historian.

While Coppola is often hailed as an “auteur” — a term to describe a director whose body of work showcases a unique style or thematic focus — I find that term of little usefulness in understanding a director’s work, particularly in a highly industrialized and fickle system like Hollywood. If anything, Coppola’s films, apart from “The Godfather” trilogy, show no aesthetic or thematic coherence. “The Conversation” shares nothing in common with “The Outsiders,” for example. However, what Coppola’s work does indicate — and this is the opposite of this auteur theory — is his ongoing enthusiasm for experimenting with film form. “Finian’s Rainbow” interjects contemporary issues into a 1947 stage musical while “Rumble Fish” draws its avant-garde style from the French New Wave and German Expressionism. That’s just two of the many eclectic approaches that Coppola brings to each film.

Q: The 50th anniversary of Coppola’s tour de force, “The Godfather,” will be commemorated in several ways this spring. What was the initial cultural impact of the movie and its impact on cinema?

A: "The Godfather" was a critical and commercial hit when it opened in March 1972, delayed three months from its intended Christmas release due to disagreements between Paramount production chief Robert Evans and Coppola over the film’s final cut. It soon supplanted “The Sound of Music” as the highest-grossing film of all time. “The Godfather’s” impact cannot be underestimated, particularly since 1969–71 turned out to be Hollywood’s worst financial stretch ever.

The box office crisis that preceded the release of “The Godfather” was due to a number of issues, including rising short-term interest rates, a new rating system, an oversaturation of films in the marketplace and an inability of the major studios to comprehend what the late 1960s audience wanted to see. “The Godfather," even more so than “Love Story,” the No. 1 film at the box office in 1970, also from Paramount, demonstrated that a single film — especially if it could be marketed as an “event” — could save a studio and, in a sense, save the industry. The film restored Hollywood’s faith in the mass appeal of a big-budget feature — though “The Godfather” was a modestly budgeted $6 million production — and confirmed that the industry’s profits would remain concentrated in a handful of enormously successful movies each season.

Q: Along with the 50th anniversary of the film, audiences will come to better understand the backstory of the movie and Hollywood with a new dramatic miniseries called “The Offer” and the film “Francis and The Godfather,” directed by Barry Levinson for HBO. What was the backdrop of Hollywood at that time?

A: Hollywood’s long-time business model from the "studio era" was no more. The industry was in the midst of a deep recession, and almost all of the major studios were purchased by non-film conglomerates tasked with making Hollywood profitable again. Movies like “Star,” “Hello, Dolly!” and “Paint Your Wagon” were expensive old-fashioned flops made by the old Hollywood regime for older audiences. The young audience saw no need to partake in the so-called “truths” of classical Hollywood entertainment and were instead drawn to films like “The Graduate,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Easy Rider.”

Out of this moment emerged a new Hollywood, or the "Hollywood Renaissance" — characterized by a series of personal, edgy, experimental, low-budget film styles across a number of Hollywood pictures from 1967 to the end of the 1970s. They were made by a gifted group of filmmakers from several realms — television, the independent world and film school — who crafted a politically subversive and aesthetically challenging body of cinema engaged with the larger social world. And armed with a newly formed rating system, directors like Coppola, Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, Hal Ashby and Terrence Malick could approach issues like sex, race, politics, language and violence in confrontational and candid ways never before seen in Hollywood.

Q: “The Godfather” is one of those films that has been enjoyed and watched by several generations since its 1972 release. Why does it continue to resonate to this day?

A: “The Godfather” came out of time in American history in which cynicism and disillusionment stood alongside a faith in the country’s traditional values and dominant social order. Such extreme divides in regard to notions of civil rights (race, gender, class, sexuality), reproductive rights, religion and democracy, among others, still exist as America still reckons with the social and cultural changes wrought by the '60s and the Vietnam War. The popularity of “The Godfather,” I believe, partly likely lies in its ability to please both factions, to be read both subversively and prosocially, progressively and conservatively, as cultural critique or crowd-pleasing entertainment. That’s because Coppola did not have complete creative control over the film; Paramount did. As Coppola said shortly after the release of “The Godfather," "The Mafia was romanticized in the book. And I was filming the book. To do a film about my real opinion of the Mafia would be another thing altogether.”

“The Godfather: Part II” provides none of the romanticization of the Corleone family and its exploits. Unmistakably, the sequel makes an analogy between the breakdown of the American family and capitalism. As Coppola said, “I had to fight a lot of wars the first time around. In ‘The Godfather: Part II,’ I had no interference. Paramount backed me up in every decision. The film was my baby, and they left it in my hands.”

Q: This year's Oscars nominations were just announced, and it has been noted that many of the nominated films, as has been the case in recent years, debuted on streaming platforms like Netflix — the most-nominated company for the third year in a row. What’s your view of this?

A: This is the new world order when it comes to the Oscars and motion picture exhibition. ... The films nominated for best picture at this year’s Academy Awards showcase an industry in flux as their distributors used different release strategies across an array of platforms that gave viewers several options to experience the film. Warner Bros. released “King Richard” simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max for a one-month period. “Don’t Look Up” had a limited theatrical release before streaming on Netflix two weeks later. Twentieth Century Studios’ “West Side Story” is still only playing in theaters more than two months after its release. Outside the best picture category, films like “Cruella” had a different strategy: It was simultaneously available in theaters and on Disney+ Premier Access for $29.99.

Widespread theater closings due to COVID-19 only expedited what was a deteriorating theatrical window (the length of time a film plays exclusively in cinema) in the movie business from 90 days down to zero days. That pandemic approach surely will continue moving forward, but we likely will see 45-day-or-less windows for many blockbuster movies and some independently-minded fare due to new agreements between the major Hollywood studios and exhibitors. In the case of a mega-hit like “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” a film may play in theaters for two months or longer.

Q: Any predictions for best picture?

A: “The Power of the Dog.” The film leads all contenders, with 12 nominations going into the 94th Academy Awards, and has received universal acclaim for director and screenwriter Jane Campion, her cast and her crew. Like several of her fellow nominees, “The Power of the Dog” had a limited theatrical release in the United States, and then premiered two weeks later on Netflix.

Neither Netflix nor any other streaming service has won the Oscar for best picture. Netflix’s best chance came in 2019 when “Roma” was the front-runner. ... Nevertheless, Netflix and other upstart streamers posed an existential threat to the way that movies would be produced, distributed, marketed and exhibited. Only a few COVID years later, and these fears now seem so quaint. The emergence of Disney+, HBO Max and others alongside Netflix and Amazon have made streaming the norm rather than the outlier. For this reason, “The Power of the Dog” faces fewer hurdles to overcome to win best picture.

Q: Coppola missed out on an Oscar for best director for “The Godfather” but made up for that loss with a win in the same category for “The Godfather: Part II.” From least to greatest, what would you say were the top five films under Coppola’s direction?

A: I believe that Coppola made four films that most people would agree are important works of art: the aforementioned films of his from the 1970s — "The Godfather," "The Conversation," "The Godfather: Part II" and "Apocalypse Now." However, he is not alone among many directors during the Hollywood Renaissance (1967-1980) who produced their best work during this decade. ... Coppola's other films fail to reach a level of achievement like his four 1970s films due to studio interference, budget issues, casting concerns or simply a lack of good judgment on Coppola’s part.

If I had to choose one film from Coppola to round out the top five, it would be a film that featured him but was shot by another Coppola, his wife Eleanor. “Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse” is the documentary record of the production of “Apocalypse Now.” Also narrated by Eleanor, the film was pieced together by directors Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper from Eleanor's behind-the-scenes footage and post-production interviews with the cast and crew. It is one of the most revealing accounts of a movie ever produced: a 238-day shoot filmed in the Philippines and beset by typhoons, a civil war and Martin Sheen’s heart attack. More so, “Hearts of Darkness” gives great insight into the man and artist that is Francis Coppola: at once genius and fool, visionary and megalomanic, alchemist and hustler. From utter chaos emerged a film of operatic proportions.

Top photo courtesy of Paramount Pictures

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

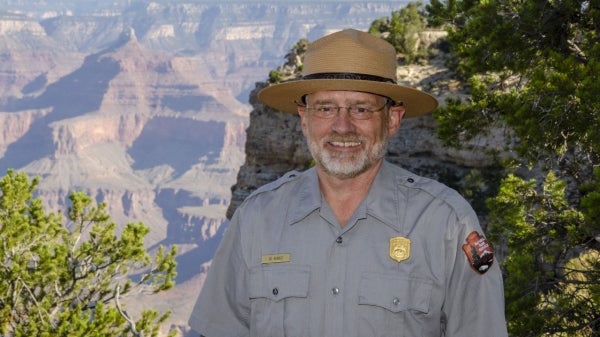

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…