ASU professor's research into teaching marginalized kids leads to top faculty honor

At Karen Harris’ first teaching job, in a fourth grade class in West Virginia, the students asked her why she cared so much about them because they were “bad kids” who were unlikely to finish high school.

Fifty years later, Harris is still moved to tears when she recalls those students, the children of coal miners.

“Many good things came out of that,” said Harris, the Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University.

“I became very concerned about how we could teach better and what we knew about teaching when students were in adverse situations.”

Those miners’ children were just the first group of marginalized kids that Harris taught. She worked with kids affected by disabilities and saw the effects of poverty and marginalization. She realized that all of the research on pedagogy was not making it into the classroom, so she switched to working in academia.

“I decided to go into higher ed because we weren’t doing the best we could,” she said.

Harris’ decades in the classroom and in research led her to create, refine and validate a unique model of instruction called Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD), which helps students learn complex topics like writing and reading by building their confidence in their abilities.

Harris is so excellent in her field that she has been named one of four ASU Regents Professors for 2022 — the highest faculty honor, which is achieved by only 3% of faculty members. She was officially inducted during a ceremony on Feb. 9.

Carole Basile, dean of the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, said that Harris has dedicated her career to kids with special needs and their teachers.

“The one skill that Karen has that makes her just an incredible researcher and colleague and teacher is the ability to do really complicated research and then be able to translate that to the practitioners,” she said.

‘Why do you care so much?’

Harris didn’t have her “aha” moment about a teaching career until later in high school. Because she studied French long enough to become fluent, “My number one goal was to fly for Pan Am as a stewardess,” she said.

But then she found out she was too short.

“That changed everything. What will I do?”

While in high school, Harris tutored kids in a Chicago elementary school, many of whom had moved with their families from West Virginia. She saw how poverty affected their education.

She went with a friend to a recruitment fair for special education teachers.

“My friend came out uninterested and I came out on fire,” she said.

“It was, ‘This is exactly what I wanted to do.’”

Harris graduated from high school in 1971, when special education was a lot different than it is today. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act had not been passed yet, and the two main groups that special education teachers were trained to teach were blind children and deaf children.

So Harris pursued a degree in deaf education. At the time, most jobs in the field were residential placements in schools for the deaf, so she also got a degree in elementary education.

Influenced by her work as a tutor in high school, she took a job as a fourth grade teacher in a West Virginia coal mining town. The school separated the students – one class of fourth graders was the children of the mine’s managers, and Harris’ students were the children of mine workers.

One day when Harris became impatient with the children’s constant fighting, one girl asked her, “Why do you care so much? Don’t you know we’re the ‘bad kids?'”

Harris gathered the class together to talk about setting goals and how to be kind to each other. Their behavior improved but she still struggled. The fourth graders’ reading ability ranged from the primer level up to the sixth grade level.

“It was impossible to meet all their needs,” she said.

“I began thinking about how in my general education degree I had learned what to teach, but in special ed I learned how to teach. I used what I learned to individualize, but it wasn’t enough.”

Harris was at the school for only a year, but before she left, she and another teacher went to the school board and convinced them to end the practice of separating the students according to their parents’ occupations.

She then moved to Nebraska and began teaching special education students.

“A lot of the kids who had disabilities or learning disabilities or emotional behavior disorders were still being hidden at home, especially if the disability was severe,” she said.

The Individuals with Disabilities Act passed in 1975 (then called the Education for All Handicapped Children Act), and one provision, called “Child Find,” required schools to locate and evaluate kids who need special education. Harris joined that effort.

“We had a brother and a sister who had been locked in a barn at night and let out during the day when the animals were let out,” she said. “They had no typical language at all.

“They were hidden because in our culture it was not OK to have a child like that. There was no help, so there wasn’t much you could do about it.”

Harris earned a master’s degree at the University of Nebraska and decided to pursue a doctorate in emotional behavioral disorders, but when she arrived at Auburn University, she was the only one who showed up, so the program was canceled. She switched to a program in learning disabilities, but there was no funding for her, so she did an assistantship in educational psychology.

“It’s how education occurs and what makes good teaching,” she said.

At the time, there were many theories about that.

“I came to believe that to develop better instruction, we had to quit arguing and integrate the theories,” Harris said.

Her assistantship was with Steve Graham, a visiting professor who came from a working-class background and was committed to social justice — like her. They married after she graduated.

“I like to say, ‘We got married and SRSD was born,’ ” Harris said.

Teaching complex subjects

While Harris had become “an aficionado of theories,” studying how different teaching models overlapped and could complement each other, Graham was studying how children learn to write.

“He shared his passion for writing instruction, which at the time was virtually unaddressed," Harris said. "Everything was reading or math. It was, ‘If you learn to read, the writing would come.’”

They designed studies together, including a pilot to see if she could coalesce various instructional components together into her first version of the Self-Regulated Strategy Development model.

“From that case study, I learned a lot about things I would have to address,” she said, recalling one boy who refused to work with her.

“I had not addressed the beliefs of kids who had been failing.”

By third or fourth grade, some students were already self-identifying as “non-writers.”

“They would say, ‘I can’t do it.’ I went back to the drawing board. Instead of ‘adjectives, verbs and adverbs,’ it was ‘describing words, action words and action helpers.’

“We talked about attribution and motivation.”

She included research from other domains, like mindfulness.

“If you’re saying, ‘I’m not good at writing,’ how will that affect your writing? We teach them to replace that,” Harris said.

Study by study, she hammered out Self-Regulated Strategy Development — although it wasn’t called that then.

“My model has had four names,” she said.

“Much to my regret, I did not name it something like ‘grit.’”

Harris and Graham went on to teach and do research for 23 years at the University of Maryland, and then moved to Vanderbilt University for eight years.

Over the years, the students they worked with went on and did further research, taking the model in new directions, such as understanding fractions and how to teach the difference between fact and opinion. Some researched how well the model worked with students who had emotional behavioral disorders or learning disabilities.

“Within a few years, we and others had studies showing that SRSD worked for everybody across whole classes,” Harris said.

There are now more than 120 studies of SRSD, and the model is used in 15 countries around the world.

Working with Self-Regulated Strategy Development in schools involves more than experiments.

“We develop partnerships with these schools. We don’t just come in and do research and say goodbye,” she said.

“In all of our work with schools, when we’re done proving it works, we give it away.”

The SRSD model also includes professional development for teachers. Harris donates all the teacher and student materials not only to the teachers who participate in the study, but also the “control” classrooms.

Unfortunately, she’s never received funding to research the long-term results of her model.

“We have very few studies of scaling up and sustainability in schools. Can you get it to get there and get it to stay?” she said.

In 2012, Harris and Graham came to ASU, where the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College impressed them with its commitment to translating research to use by teachers in the classroom.

“It was exciting because they offered additional resources to support our work,” she said.

After nearly 50 years in the field, Harris laments that special education research and services to children are both still underfunded.

“Special education is mandated, but neither the state nor federal governments provide enough funds to do everything in the mandate,” she said.

“And it’s largely because we don’t want to pay higher taxes for education.”

Next year, Harris plans to become an emeritus professor, dedicating all her time to research, and the award of Regents Professor will likely help her do that, she said.

Graham, the Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, was named a Regents Professor in 2021.

Harris had stopped thinking that she might one day become a Regents Professor, so when she was called to a meeting with ASU President Michael Crow late last year with three other professors, she suspected nothing.

“We walked into the room and there’s this huge conference table full of all the provosts and assistant provosts,” she said.

“We were wearing masks but I think every one of us gasped.

“I was shocked and humbled and overjoyed.”

Top photo: Karen Harris, the Mary Emily Warner Professor of Education in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, has been named a Regents Professor. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

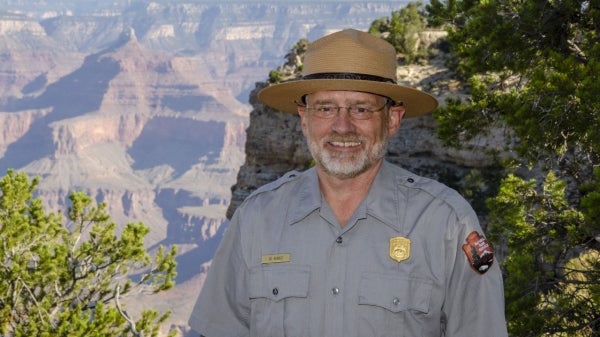

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…