George Beakley Jr.’s eldest son remembers his father as having been “a tough guy” and a “stern taskmaster.” George Beakley III intends that description as one of praise.

Yes, the longtime professor and engineer could be demanding of students, assistants and even colleagues, but he was a model of self-discipline and commitment to his work, his passions and pastimes, Beakley III says.

His portrayal is echoed by some of those who worked with or for Beakley Jr. at various times during his four decades in higher education. Beakley Jr.’s role as a teacher and administrator spanned from the mid-1950s into the 1990s, starting in the years when the small Arizona State College began its ascent into today’s ever-expanding Arizona State University.

Beyond teaching and management duties, Beakley Jr. was among those who took the lead in crusading for expansion of the college’s educational offerings and its elevation to a university.

He is remembered today as one of the key players in setting the stage for what became ASU’s College of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and later today’s thriving Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, one of the largest engineering schools in the country.

“My father was at his best as a motivator of students,” Beakley III says, adding that he also applied that skill to other endeavors, most significantly in energizing fellow academics, school administrators and Arizona public education and government leaders to get on board with a vision for broadening aspirations for higher education in the state.

Beakley Jr. and Lee P. Thompson are credited for spearheading the efforts that brought advanced engineering education to the new university. Thompson would become the founding dean of the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Beakley Jr. would continue to be either an instigator, collaborator or supporter for numerous ventures to bring more resources to engineering and related science degree programs.

Defining core concepts of engineering program

Much of the progress of ASU’s early engineering programs can be traced in large part to Beakley Jr.’s work, says Thomas Schildgen, an emeritus professor who helped lead ASU’s engineering-related graphic information technology program for 35 years.

“People respected him because he was straightforward and hardworking. He kept things moving forward and came up with ideas to improve things when they weren’t working well,” Schildgen says. “I think of him as something like the father or the soul of engineering (at ASU) at that time.”

Beakley Jr. was “a teacher’s teacher” and the “prime mover in defining the core concepts” of engineering education during ASU’s formative years, says his longtime ASU colleague, Emeritus Professor Charles Backus, who oversaw the establishment of what would become ASU’s Polytechnic campus and home of the Polytechnic School, one of the seven Fulton Schools.

Beakley Jr. put Backus in charge of the first ongoing efforts to establish relationships between the engineering program and industry, and he gave Backus strong support to do the job. That foresight set the stage for the Polytechnic School to become a center for innovation and industry partnerships that it is today. Beakley Jr. lent a guiding hand for everything from how first-year ASU students were introduced to the field of engineering to how they eventually got put on track to jobs and careers, Backus says.

Validation of Beakley Jr.’s range of talents came by way of winning three of the top teaching and engineering educator awards from the American Society for Engineering Education, plus its annual award for the year’s most outstanding technical paper on engineering education.

Accomplishments as author, athlete and musician

Beyond his teaching and management achievements, Beakley Jr. was “astoundingly prolific” in other pursuits, Backus recalls.

He authored or coauthored more than 30 textbooks, some of which were bestsellers, including at least one, “Engineering: An Introduction to a Creative Profession,” that was reported to be used by at least 50 colleges and universities.

Various newspaper feature stories highlighted his work in mentoring and educating young engineering teachers and in developing new courses to keep up with growth and innovations in engineering and science fields.

Beakley Jr. had an equally long list of achievements dating from before his days as a professor. He was the valedictorian of his high school class and lettered in track, tennis and baseball. He won a young artists competition for his skills as a concert violinist and earned college scholarships in both engineering and music. During college, he excelled in fencing, and he ended his college days with doctoral degrees in both mechanical engineering and industrial engineering. He also earned the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

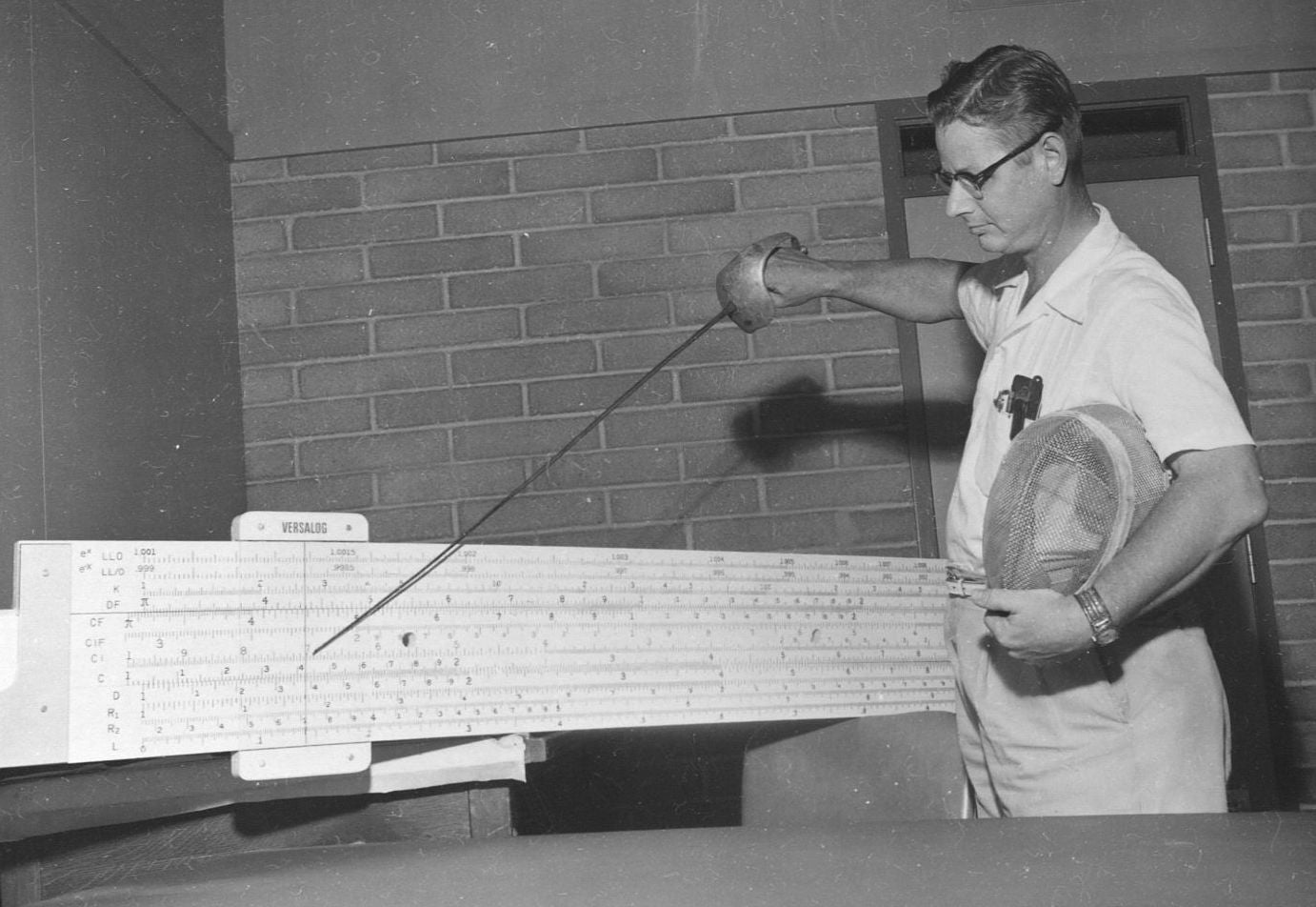

Though he had a reputation as a demanding and serious-minded teacher and academic leader, Professor George Beakley Jr. could show a humorous side. He sometimes displayed the pictured 10-foot-long slide rule in his classroom and office and carried his sword from his days as an accomplished competitive college fencer. Photo courtesy of University Archives/Arizona State Library

Opening doors to opportunity for students

Beakley III says his father would have measured his success not primarily by his career accolades but by how he impacted the students he taught and guided, as well as the colleagues with whom he collaborated to boost the evolution of engineering education at ASU.

Wayne Headrick says he is grateful that back in the 1960s Beakley Jr. “had the foresight to see how computers and computer education were going to be essential in every area of engineering.”

Beakley Jr. was largely responsible for creating a program enabling U.S. Air Force technicians and engineers like Headrick to advance their knowledge of computers at ASU. That education was a foundation for Headrick to become a computer programmer and earn an engineering and science degree and later a master’s degree at ASU, leading to a long career in the military and industry as a programmer and educator.

Jim Grose remembers doing poorly in his early studies at ASU in the late 1950s. Calculus, in particular, looked like it would be his downfall. Fortunately, he says, Beakley Jr. was among the teachers who were “tough but fair” and worked with him to improve his academic performance.

Though he switched from engineering to construction, Grose graduated in 1964 and went on to a successful career in the field. He still has one of Beakley Jr.’s textbooks and maintains his use of the slide rule — one of the tools of engineering at the time and a concept he learned in Beakley Jr.’s class.

Sarah (Butterfield) Nucci worked as Beakley Jr.’s secretary during some of his time as the interim dean of the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and she saw him help many students overcome their challenges.

“He was a real no-nonsense type of guy who had a lot of ambition and energy, and was very firm about how he wanted people to perform,” Nucci says. “But I learned from him how not to be intimidated by problems and how to move forward. I think he taught that to a lot of students.”

Emeritus Professor William Lewis , a colleague of Beakley Jr.’s over most of their long tenures at ASU, says one of Beakley Jr.’s most impactful strengths was not only telling students what to learn but showing them how to learn.

“To him, that was a cornerstone of being an engineer,” Lewis says. “Engineers solve problems, and you can’t always do that just by being taught something. You do it by knowing how to learn on your own.”

Erecting foundations for a new university

Beakley Jr. and Thompson no doubt faced one of their own most intense learning curves in their daunting undertakings to establish a full-fledged engineering program at Arizona State College — and at the same time aid the seeding of a movement for the school to evolve beyond mere college status.

At that time, now well over half a century ago, neither the Arizona Board of Regents, nor state government leaders, nor the leadership at the University of Arizona were big on the idea.

To overcome that resistance, Beakley Jr. and Thompson had to map out a new curriculum that defined something distinctly different from what was offered by the state’s only university at the time.

They also helped catalyze community support from other education leaders and proponents of the college’s growth, making their case to the Board of Regents while fending off opposition from objectors. They then joined other supporters to navigate the exacting process of bringing an initiative on the proposal to a statewide public election.

In the spring of 1992, the year he retired, Beakley Jr. — then the director of the School of Engineering within the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences — gave the convocation ceremony address to new graduates of the college. He used the occasion to tell the story behind the initiative that turned the state teachers college into Arizona State University.

Beakley family’s legacy at ASU

The Beakley family’s long history at ASU has continued over the past several decades, strengthening the family’s legacy of the value Beakley Jr. put on higher education.

George Beakley III graduated from ASU with a bachelor’s degree in engineering science in 1970 and earned a master’s degree in industrial and management systems engineering the following year. His wife, Penney Beakley, had earned a master’s degree in counseling in 1969.

Another of Beakley Jr.’s sons, David, earned a master’s degree in industrial engineering, and daughter Martha earned a master’s degree in technology. Martha and Beakley III also collaborated with their father on work for a few of his textbooks.

One of Beakley III’s daughters, Sara Mercill, earned a degree at ASU in industrial technology in 1997 and recently completed studies for a master’s degree in graphic information technology. Her husband, Scott Mercill, graduated with an industrial technology degree in 1998.

Sara and her sister Amanda, who holds bachelor’s degree in education and a master’s in special education from Northern Arizona University, are also carrying on the family legacy as teachers.

Beakley III is scheduled to honor his father’s legacy when he speaks at the fall 2021 Fulton Schools convocation ceremony in December and gives a diploma to the family’s latest Fulton Schools graduate, his daughter Sara.

Top photo: Over four decades as a professor, George Beakley Jr. (second from right) earned numerous accolades at a national level from his professional peers in engineering and education, wrote numerous textbooks, served as both an associate and interim dean, and was a leading figure in the campaign to create Arizona State University. Photo courtesy of University Archives/Arizona State Library

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…