“Let’s go save some lives.”

Seven days a week for months on end, that’s how Josh LaBaer ended his 8 a.m. meeting with the Arizona State University team that was developing a new kind of test for COVID-19.

After the first month, he decided to stop saying it.

“But everyone told me that I had to keep saying it,” he said.

“It was something that informed every decision we made. Everything we did, the fundamental question was, ‘What will save the most number of lives?’ ”

LaBaer, who is executive director and professor of the Biodesign Institute at ASU, discussed his team’s efforts during a webinar presented Wednesday by the Economic Club of Phoenix, which is part of the W. P. Carey School of Business.

LaBaer’s team developed the qPCR diagnostic test at the beginning of the pandemic and scaled it up in mere months thanks to an unimaginable level of teamwork and an innovative approach.

Along the way, ASU built a new lab, the ASU Biodesign Clinical Testing Lab, which gained certification initially for testing nasopharyngeal swab samples and then became the first in the western U.S. to offer and run public saliva tests for coronavirus.

The lab will soon surpass a million test samples.

LaBaer described the timeline, starting back in February 2020, when public health officials noticed that the coronavirus was spreading quickly outside of China.

At that time, there was almost no testing capacity or supplies in Arizona.

“The only tools available to us were keeping people separated and finding ways to test people to tell them if they were infected so they could quarantine,” he said.

“I talked to President Crow, who was justifiably concerned that with well over 100,000 souls at this university, how would we get them tested?”

LaBaer was on a phone call in early March 2020 with all of the hospitals in the state.

“We tallied it up and there were probably 1,000 nasal swabs in the state of Arizona at that time and virtually no (personal protective equipment),” he said.

Josh LaBaer, executive director of the Biodesign Institute, described how his team dealt with pandemic shortages of testing supplies during a talk Wednesday sponsored by the Economic Club of Phoenix, part of the W. P. Carey School of Business. Screenshot by Charlie Leight/ASU News

LaBaer said that his lab was already working on a research problem using the core technology for testing.

“Could we pivot that technology and know-how from testing radiation responsive biomarkers to SARS COVID-19?” he said.

They could. The lab developed the rapid and accurate qPCR test in March.

By April, the lab was testing first responders and hospital staff, and by June it had partnered with the state Department of Health Services to provide free public testing around the state.

Saliva tests were a game changer, he said. They are less invasive and less uncomfortable, as well as safer for the health care workers.

“If you put a stick in someone’s nose, they will cough or sneeze and put the virus on the health care workers,” LaBaer said.

The workers doing the nasal swab tests had to wear head-to-toe personal protective equipment, which was difficult to find.

Plus, the drive-through nasal-swab tests could only produce 25 samples per hour per lane.

Health care workers are not needed to administer the saliva tests, in which people spit into a tube.

LaBaer emphasized that the work required an interdisciplinary team.

“We had to develop tools for training people in how to collect samples. We had visual aids, instructional videos, methods for storage and shipment,” he said.

“We had to collect data in a fashion that was HIPAA compliant to maintain privacy. It had to be easy to do on a phone and send text alerts when test results are ready.

“All of this had to be tracked with informatics. We needed quality systems in place, which meant lots of documentation of every step in the process.

“And all of that had to be communicated.”

That’s why the team met every morning for nine months. In the beginning of the pandemic, seven people were on the call, but it eventually grew to 140 people.

“We wanted every team to report every day so that everyone knew what everyone else was doing,” he said. “One reason for that level of communication was that we couldn’t allow a mistake to last for more than 24 hours.

“We made a lot of them, and we had to find them and fix them quickly.”

He described the process as “moving train dynamics.”

“To get to scale, we had to be constantly innovating. We had multiple teams innovating simultaneously,” he said.

“As soon as we got an innovation in place, they had to leap onto the train and add it so we could move the whole train faster.”

He described one challenge the team faced: They knew they needed a machine to uncap the sample tubes.

“We have a device that will uncap 24 tubes at a time in roughly 20 seconds, a lot quicker than people could do it,” he said.

“There are individual motors for each tube, and the motors were dying on us. It turns out that if the rate at which you lift the cap off is too slow, it wears out the motor. Who knew?

“You have to fail quickly and adapt quickly.”

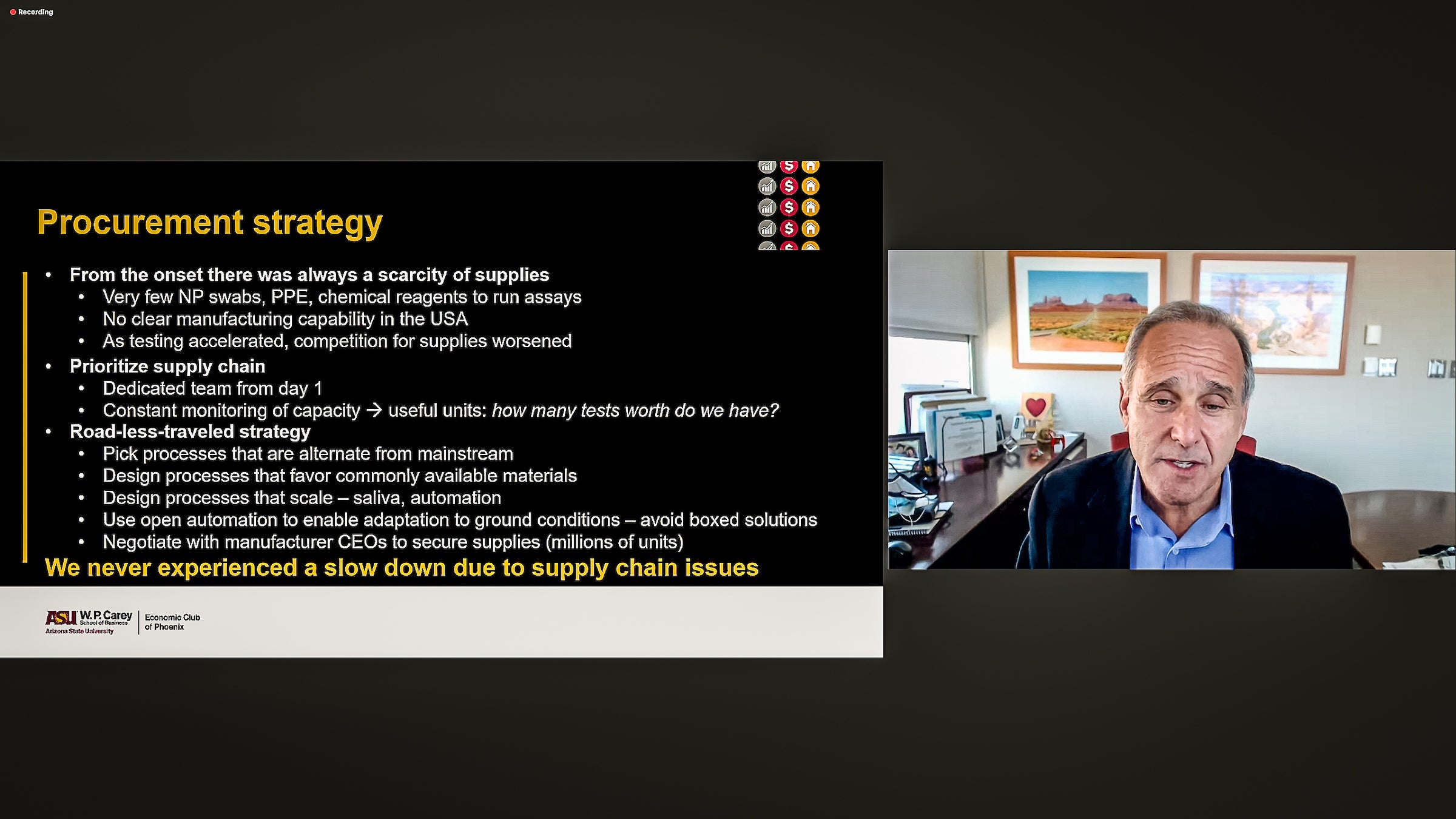

Critically, one team was dedicated to procurement strategy, or “finding stuff.”

Swabs, personal protective equipment, chemicals needed for testing and other items were in short supply. The United States had no manufacturing capacity. Most of the inventory was coming from overseas.

“We knew that as testing accelerated in the state and the country, the competition for supplies would get even worse,” he said.

They took the “road less traveled” strategy.

“We designed all the processes to follow the path that everybody else was not following, so there would be more availability of supplies,” he said. “We always used an alternative compared to what everyone else used.”

For example, using regular plastic drinking straws in the saliva test kits was a critical innovation.

“They’re much easier to use than medical devices, and they are key because they prevent phlegm or snot from getting into the samples, which would ruin the results,” he said.

Test-takers use the straw to deposit their saliva into small plastic tubes that are labeled with bar codes. LaBaer said that his procurement team convinced a manufacturer of the tubes to dedicate one of its plants to ASU’s efforts.

“That kept us running. We never experienced a slowdown due to supply chain,” he said.

The turnaround time for test results has never been longer than 48 hours, he said.

LaBaer said the lab is now soliciting staff and student volunteers on campus to give blood samples for antibody tests.

“That will give us some sense of how many still remain COVID-19 naïve — unvaccinated and uninfected,” he said.

“If that number is small, we are likely to not see another big wave.”

LaBaer noted that the Biodesign Institute was founded with money that voters approved by passing Proposition 301 in 2000.

“People don’t appreciate the wealth of knowledge we have at places like ASU, where we have so many people with so much experience that we can get something like this up and running so quickly,” he said.

“It’s a testament to the investment the state has made in its own people.”

Top image: An ASU student submits a saliva sample for residence hall testing in 2020. Josh LaBaer, executive director of the Biodesign Institute, said that using regular drinking straws in the test kits was critical because they were not subject to pandemic shortages. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…