When it comes to American history, ASU Foundation Professor Lois Brown believes no story is too small to tell.

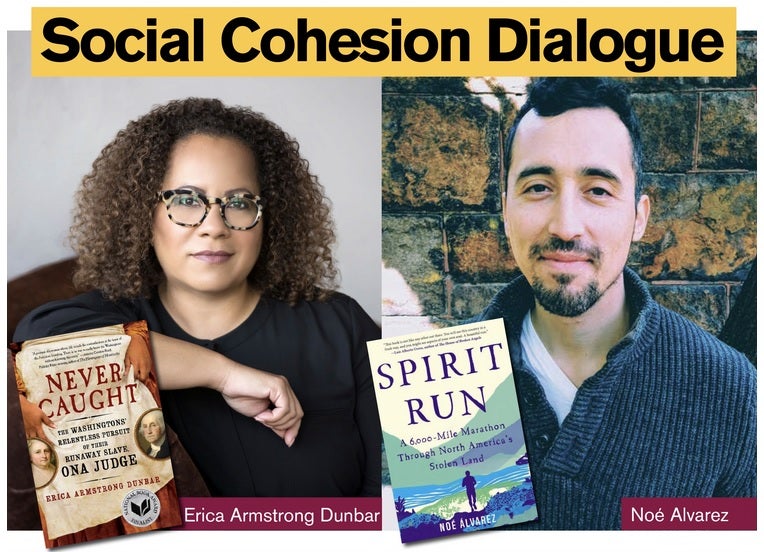

On Thursday, Feb. 18, the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, for which Brown serves as director, will host authors Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Noé Álvarez for its annual Social Cohesion Dialogue, which puts acclaimed authors and their books in conversation with ASU and Arizona audiences about issues of race, class, environmental justice, civil rights, economic inequality and social justice.

And the stories Armstrong Dunbar and Álvarez have to tell are far from small. In “Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave Ona Judge,” Armstrong Dunbar recounts the titular character’s fight for freedom, and in “Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America’s Stolen Land,” Álvarez relays his own personal journey from working in an apple-packing plant to becoming a first-generation Latino college student — a journey that led him to join a Native American/First Nations epic marathon meant to renew cultural connections across North America.

“It's really painfully clear in both of these books that when an individual decides that they want to act on their own behalf, it has incredibly complicated ramifications,” Brown said. “And so both of these books give us a way to think about American culture and history, and I think — even more importantly — they prompt us to start asking more nuanced questions about the America we think we know, want to know more about and want others to talk with us about.”

Brown will moderate the dialogue on Feb. 18, which will be held virtually via Zoom.

ASU Foundation Professor Lois Brown

Question: Why did you choose the books/authors you did for this year’s dialogue?

Answer: It’s always a festival of plenty when it comes to thinking about which books to feature in the Social Cohesion Dialogue, but one of the things that prompted these books to rise to the top is the power of revelatory story. We are living at a time when — in relation to issues of race, ethnicity, difference and diversity — so many people are saying, “I didn't know.” They didn’t know that systemic inequality existed or was made manifest in these ways, or they had no idea that American history included these lessons about founding fathers and their families and their relation to enslavement or to settler colonialism or to racial stratification.

(Álvarez) is a Mexican American immigrant, and his book is not only a powerful coming-of-age story, it’s also a story about borders. So it allows us in Arizona to think about the history of this state and the ways in which Mexican Americans are an integral part of our culture, our society, our history and our leadership. It's a very humble and straightforward meditation on the difficulties of belonging and the possibilities of how one comes into knowing oneself.

(Dunbar’s) book is a revelatory history about George Washington, an individual many people think they know. This is a book that takes an absolutely critical historical moment from America’s beginnings and situates it in the larger context of power hierarchy, enslavement, pursuit and oppression. And it's also a book about agency. It sheds a light on the kind of costs that are associated with striking out on one's own.

Q: It has been almost a year since the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy hosted a public lecture series in response to the killing of George Floyd. One of the resounding takeaway messages from that series was the need for individuals to educate themselves about racial issues. Do you think any progress has been made in that respect since then?

A: I do think the tide is moving, but it's important to find places of hope. Because even as things are changing and more people are coming into consciousness, we also see absolutely unsettling demonstrations of resistance coming from predominantly white corners on days like Jan. 6, and that was not an isolated event. But I would say that, coming out of the summer of 2020, which was incredibly traumatic for so many people and really highlighted multiple vulnerabilities, that there has been a sort of ripple effect of impact. It seems based on the kinds of initiatives that people and institutions like ours are taking, that more people being fueled by a desire to know more, to be present, to be vigilant and to figure out how best to bear witness to what either needs to be done or what needs to stop being done.

There is still a lot to be learned about systemic inequality and its reach and how rooted it is and what anxieties it's provoking in those who think that inclusion means their exclusion. But we have to turn towards the light, do we not? I also think that with all the violence, with all the trauma and hurt and disproportionate impacts of the pandemic, that it's becoming increasingly difficult — and I hope impossible — for people to say, “I did not know, I did not see, I did not hear.” And then once you see these things, it compels action. It compels response. And I see more people leaning in to respond in ways that are constructive and purposeful, and that should give us more hope.

Q: What do you hope people take away from the dialogue on Feb. 18?

A: Oh, many things. In no particular order, I hope they see that despite all the odds against us right now, it's still possible to gather in good company and talk about amazing books with really gifted and insightful people. I hope that people see the power of their own voices and their own stories, and that no story is too small to tell. That what we navigate as individuals and as members of organizations or communities is part of a larger set of American stories about place and power and aspiration; about overcoming incredible obstacles and about learning as many languages as needed to try and communicate as best we can about issues of justice and peace.

I hope people come away with a real sense that American history is definitely not static. That we still have so much to add, locate, identify, document and incorporate when it comes to teaching and thinking and writing and reading about American histories.

And I hope people come away with a sense that while endings can be untidy and seemingly unresolved, it's OK to live in that place of incompleteness, because it gives us all an opportunity to think, “How else might I contribute here? How else might I learn more?” I hope that people come out of it with a sense that it's not about casting aspersions; it's about expecting that there's more to every single story we encounter, and that we need to create a culture of asking purposeful, thoughtful, evocative questions of each other.

Top photo courtesy of Pixabay

More Law, journalism and politics

ASU experts share insights on gender equality across the globe

International Women’s Day has its roots in the American labor movement. In 1908, 15,000 women in New York City marched to protest against dangerous working conditions, better pay and the right to…

ASU Law to offer its JD part time and online, addressing critical legal shortages and public service

The Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, ranked 15th among the nation’s top public law schools, announced today a new part-time and fully online option for its juris doctor…

ASU launches nonpartisan Institute of Politics to inspire future public service leaders

Former Republican presidential nominee and Arizona native Barry Goldwater once wrote, "We have forgotten that a society progresses only to the extent that it produces leaders that are capable of…