It’s the night of Sept. 13, 1923. Ten men are deep in the Grand Canyon. Their expedition — to map the river corridor — marks the end of the era of exploration in the canyon.

But that night the river is trying to end them.

Unseen upstream rains cause a surprise flood. All night long, the river climbs. The men scramble in the darkness, tripping over rocks, repeatedly moving their gear and boats to higher ground.

The river doesn’t stop. It rises 14 feet in one night. After daybreak, it rises another 7 feet. Unbeknownst to the men, the outside world thinks they are dead.

The water flow rate has risen from 10,000 cubic feet per second to 125,000 cubic feet per second. In 2021, with Glen Canyon Dam controlling the river, typical flows are around 13,000 to 17,000 cubic feet per second. A 30,000 cubic feet per second flow is sporty. You’d better know what you’re doing on the water.

But to witness a flow of 125,000 cubic feet per second is to stare into the face of God.

The party waits three days, miserably crouched amongst boulders high up on a slope, before water levels drop to the point where their survey point is exposed again and they can continue work. When they arrive at Diamond Creek, long overdue, someone brandishes a newspaper. "HOPE NOT GIVEN UP FOR RIVER PARTY!" the headline thunders.

The nation hadn’t forgotten them. And, almost a century later, their work is still remembered.

Arizona State University Library’s Map and Geospatial Hub has just unveiled a dynamic multimedia exhibit describing, explaining and celebrating a historic collection of maps and charts of multiple Colorado River surveys conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey between 1902 and 1923.

“Visualizing the Survey” visually dissects and simplifies the mechanics of these technical and beautiful survey sheets, while putting their historical and geographical significance in perspective.

Matthew Toro, a research geographer and director of Maps, Imagery, and Geospatial Services at the ASU Library, explained the impetus behind the project. He was inspired over the course of several hikes in the canyon.

“I started thinking about the role of maps in making us sort of internalize and come to terms with the scale and the grandeur of the Grand Canyon,” Toro said. “I started asking questions about how this thing was mapped. And obviously that continues to be sort of a ball of yarn that I continue to unravel because new questions and new lines of interrogation open up. The truth is if you want to know about how the Grand Canyon was mapped, it really starts with what created the Grand Canyon. And that, of course, is the Colorado River. … It started with (the government) saying, we need to map the Colorado River for strategic purposes, for scientific purposes, et cetera.”

John Wesley Powell, the one-armed Civil War vet who first traveled through the canyon on the river, did some mapping on his second expedition, but nothing significant. Clarence Dutton’s 1882 atlas of the canyon treated the entire area, but not the river corridor.

The USGS did a number of surveys of the American West from the 1880s onward. Simply put, Congress didn’t know what was out there and wanted to find out.

The Birdseye expedition in 1923 was the last of the government surveys. It’s legendary among river runners to this day.

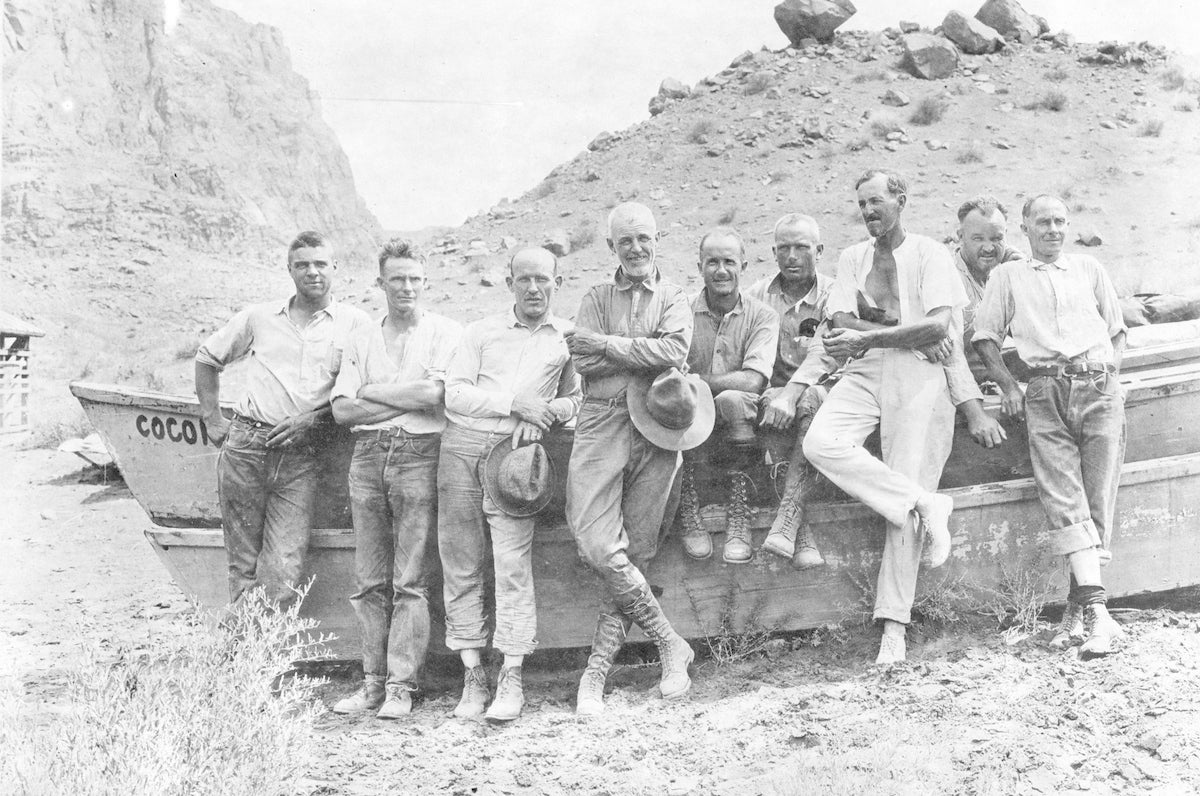

Party at Lees Ferry. Left to right: Leigh Lint, Elwyn Blake, Frank Word, Claude Birdseye, Raymond Moore, Roland Burchard, Eugene La Rue, Lewis Freeman and Emery Kolb.

“The 1923 trip is an amazing feat,” said Tom Martin, founder of River Runners for Wilderness and the Grand Canyon Private Boaters Association. Martin is also the author of river and hiking guides and a volunteer for the Grand Canyon Hikers and Backpackers Association and the Grand Canyon Historical Society. He is widely acknowledged as the leading expert on canyon river history.

“They ran a level line survey in oar boats for 260-some miles and closed within 4 feet (of the starting survey from downriver). There’s some very cool history there, including a flood from the Little Colorado River that came down on them as they were working their boats around Lava Falls. … These maps, including the Glen Canyon, Cataract Canyon, Green, upper Colorado, and San Juan surveys were all completed in the early 1920s and ended the era of exploration. They were used extensively by later river runners. The oldest river guide I have found is from 1950. It uses these maps.”

The intent was to explore possibilities for power generation, identifying potential dam sites. Claude Birdseye, the chief topographic engineer of the USGS, led the expedition. A lot of historic Grand Canyon names were on the trip, including Emery Kolb, who ran a photo studio at the canyon from 1902 to 1976.

Kolb and his brother ran the Colorado from Wyoming into Mexico in 1911 and made a film and a book about it. He was notoriously possessive about the canyon for decades, especially toward anyone else who dared to tote a camera. On the Birdseye expedition he fought constantly with Eugene LaRue, hydraulic engineer and official chief photographer. At least one writer has described Kolb as an “emotional ball of fury.”

Repairing a boat after running Badger Creek Rapids. Left to right: Claude Birdseye, Leigh Lint and Emery Kolb.

Elwyn Blake worked as a boatman on all three of the USGS expeditions: down the San Juan in 1921, the Green in 1922 and the 1923 trip. A novice when he began, Blake became the consummate big water man. These weren’t zip-from-camp-to-camp trips. The men had to maintain a line of sight from one survey point to the next, so they had to land – and hold their positions — every few hundred yards, even in rapids or where the canyon walls were almost vertical. Small wonder Blake’s name comes up around campfires at night almost a century later.

They floated for two months and 19 days, from Lees Ferry to Needles, California. In all they selected 29 potential dam sites.

“We're now entering the phase beyond where they're just establishing the sheer physical geography and entering the phase where they're actually saying, ‘OK, how do we control this physical geography? How do we dam the river? How do we make it productive for our own human interests?’” Toro said.

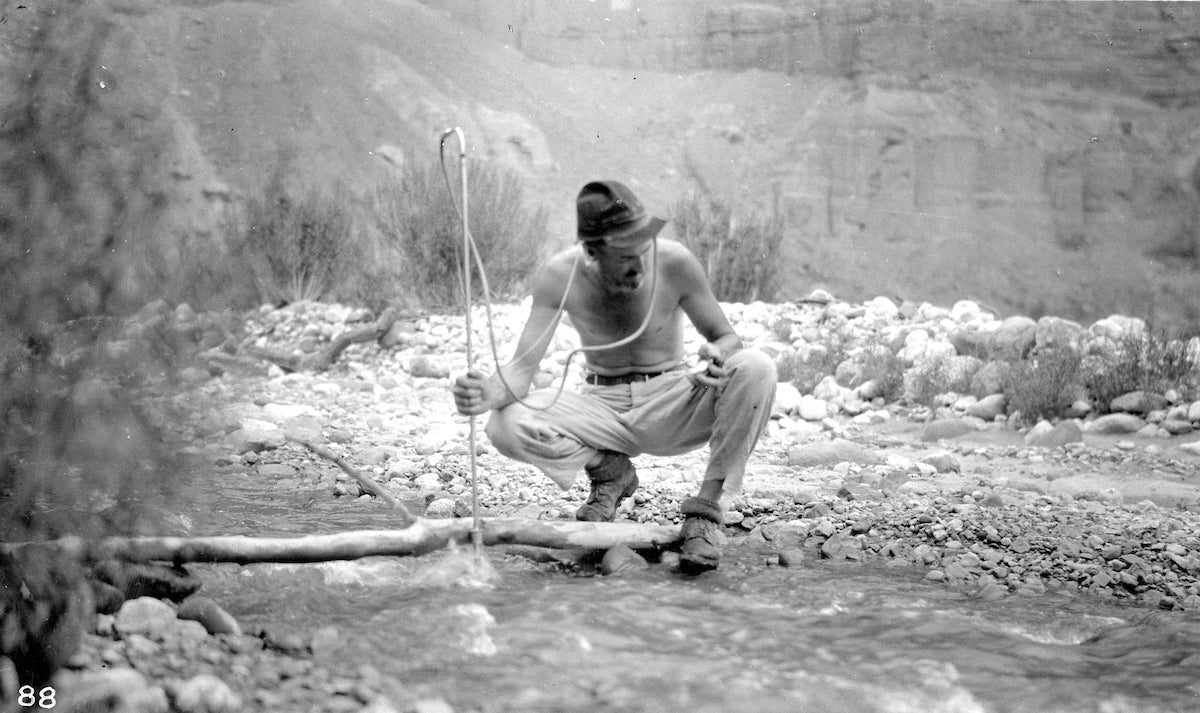

Eugene La Rue, hydraulic engineer and chief photographer, measuring the discharge of Nankoweap Creek. Every stream adjoining the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon region was measured. Grand Canyon National Park, Coconino County, Arizona. Aug. 12, 1923.

The visualization shows the historical surveys in relation to things like modern river mile markers.

“We've actually overlaid them with historic aerial photography before the Glen Canyon Dam created Lake Powell,” he said.

The Birdseye maps were ultimately used in the creation of two dams and a number of water diversion projects. Researchers today continue to use the maps, photographs and survey points — almost 100 years after they were collected.

“They're really significant,” said Bob Davis, chief of cartographic data services for the National Geospatial Program of the United States Geological Survey. “They provided quite a foundation to what became the topographic map division. So they were some of the earliest topographic surveys of anything West. Basically it became the foundation to what became the topographic mapping program that is still active today.”

It took almost a century to topographically map the United States, according to Davis. He was in a photographic unit creating new drafting topographic maps when the first coverage was completed around 1990. (These would be the 7.5-minute, 1 to 24,000-scale topographic maps you buy at outdoor stores.)

Eugene LaRue gauging flow of Havasu Creek.

How would the USGS carry out the same project nowadays? Would they be on the river on a boat?

“I would not,” Davis chuckled. “I would be doing some type of airborne elevation data collection with lidar (light detection and ranging, a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges to the Earth), or if you needed something in the river, some water penetrating lidar of some kind to get that terrain and then use digital means to represent that on a map or other products. … You can do a lot from satellite, but in today's technology, I think it would still be aircraft.”

About the only reason they would be on the ground at all is to lay some foundational elevation points to set data to make sure they were in the right elevation space.

“And there's probably enough control already set through the National Geodetic Survey or others that you could use existing points,” he added.

That means no tents blowing over in the middle of the night, sandy food, filthy songs, rattlesnakes in bedrolls, personality conflicts or tedious repairs of damaged boats. Unlike 1923.

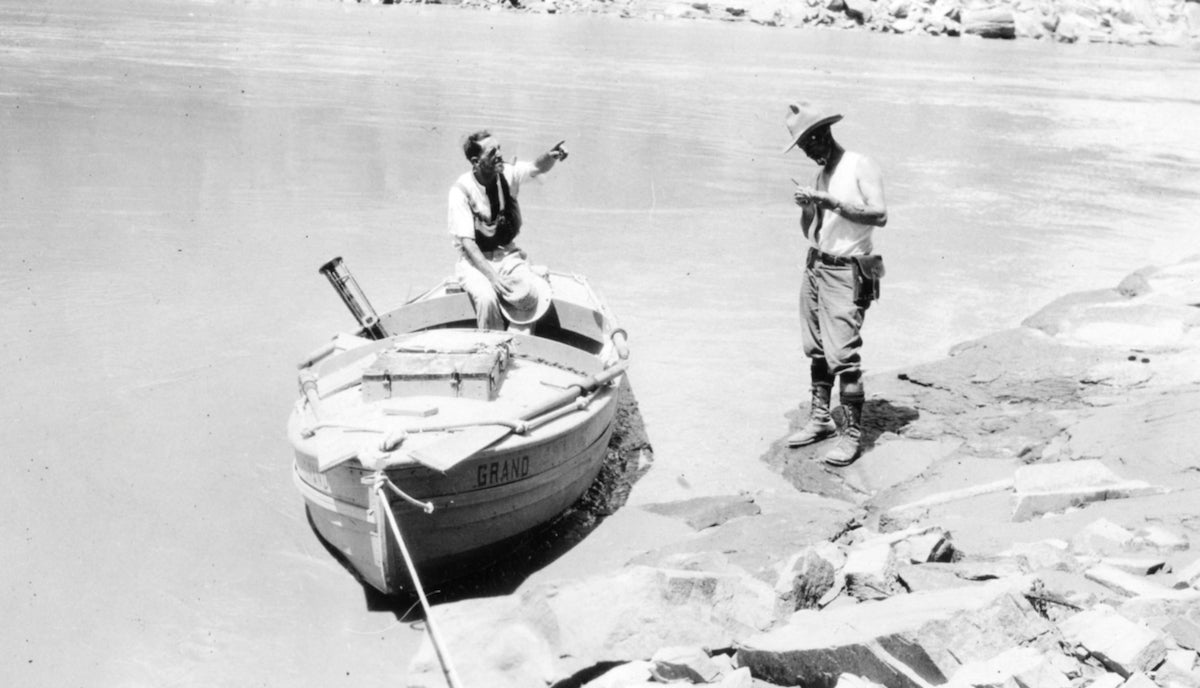

Hydrographer Eugene LaRue and geologist Raymond Moore, Mile 3, Marble Canyon. Photo by Lewis R. Freeman.

Four of the five boats on the Birdseye expedition survived. (A canvas boat gave up the ghost before Marble Canyon ended, completely destroyed.) Injuries abounded.

“The three members of the party on the Grand are the only ones so far not reporting ailments,” celebrity adventure writer Lewis Freeman penned in his diary. “Probably this will not last long.” They did things no one would do now, like throwing cans in the river to see where they ended up. They also lit several acres of driftwood on fire on the Unkar Delta to let people up on the rim know where they were.

Some people left the expedition at Phantom Ranch and others joined. Emery Kolb flipped in Upset Rapid and almost drowned.

But it wasn’t all misery. In the middle of it, they all hiked up to the Rim for a resupply trip, where they had hot showers, gorged on fresh food, donned suits and went to a dance.

The expedition took out at Needles, California, but the USGS mapped the river corridor all the way to the Mexican border.

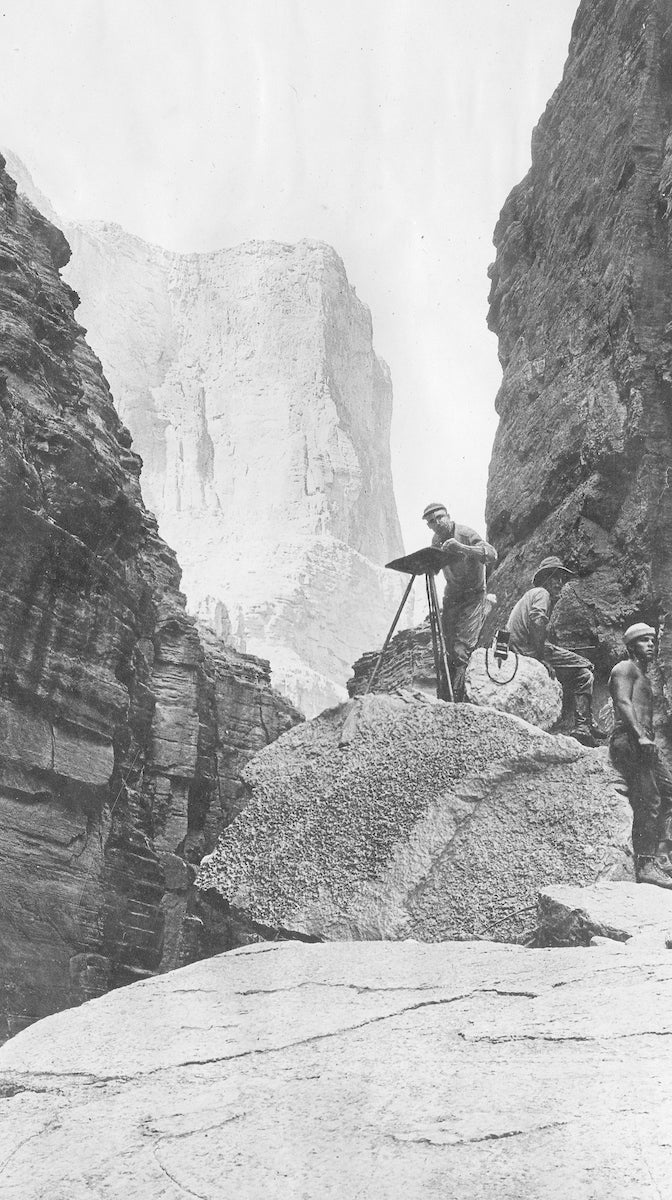

Survey of canyon of Cataract Creek 9.6 miles below Havasu Creek. Left to right: surveyor Roland Burchard, expedition leader Claude Birdseye, boatman Leigh Lint. Grand Canyon National Park, Coconino County, Arizona. 1923.

“One thing that we wanted to do with this project is sort of make this really essential water artery that runs through the entire Southwest of the United States, try to really visualize it and show people what the river looks like and where it goes,” Toro said. “Because ultimately we all depend on the Colorado River in one way or another. So I'm sort of making the geography closer to home for people.”

Production lead was Remi Tuijl-Goode, a junior majoring in music and art history.

“I would work on it every day that I came in, either scanning maps or referencing things or using Photoshop to make imagery and kind of collect it all together,” she said. “I was attracted to working in the library and to working with historical artifacts because that's something that I want to pursue.”

The original maps are in the library collection, bound in volumes. They’re accessible to anyone who would like to see them, but putting the collection online opens it up to anyone in the world with an internet connection, Toro said.

The expedition concluded with sunburns, minor injuries and weathering, but no one died. Birdseye went on to lead the division of engraving and printing at the USGS.

“That was a pretty significant person to be involved in our topographic mapping,” said Julie-Ann Danfora, historical topographic map collection program manager at the USGS. “He was kind of at the forefront of all of the technology that was vastly changing at that time. So it was really great to have him working on our topographic maps or at least leading the charge. Those surveys and early expeditions did form the foundation of what became the topographic mapping program. So pretty important from that standpoint that it shaped the minds and thinking of several of our leaders of topographic mapping.”

More Science and technology

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking risks, having a hard time resisting temptation, difficulty getting…