College town vs. education center: ASU researcher examines geography of higher ed

New research co-led by Meagan Ehlenz, assistant professor in ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, provides the most detailed picture to date of the geography of higher education institutions across the nation.

Colleges and universities are vital for driving local economies for many U.S. cities. Having higher education institutions present aligns with a host of benefits, from employment opportunities to housing options to social life and individual opportunities — but not all places across the country have the same kinds of access.

Researchers have long understood anecdotally that metropolitan areas are influenced by their local universities, but the way in which higher education institutions are different and how they impact their metropolitan regions differently has yet to be quantified and fully understood.

New research co-led by Meagan Ehlenz, assistant professor in Arizona State University's School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, provides the most detailed picture to date of the geography of higher education institutions across the nation.

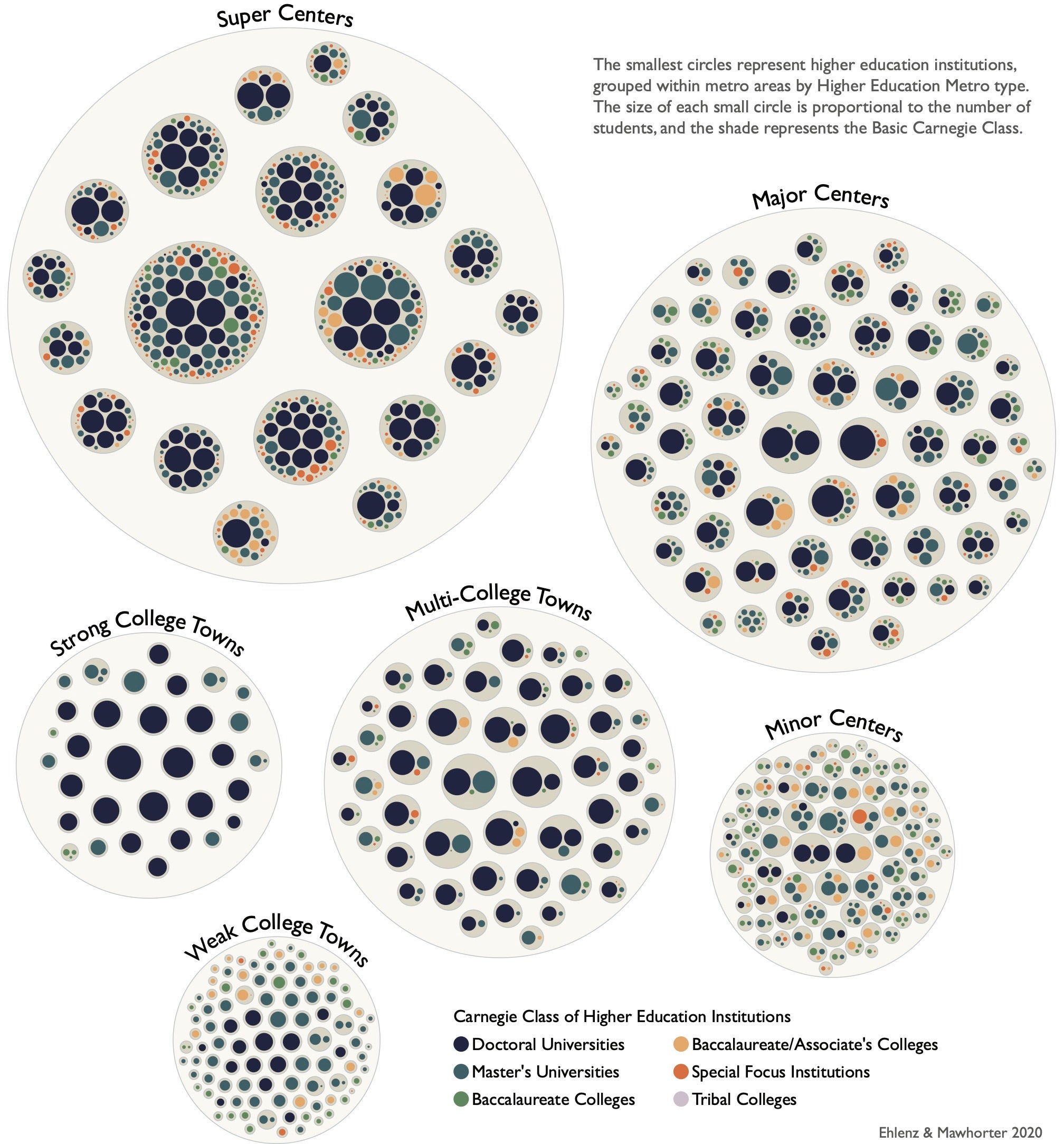

In her study titled “Higher Education Centers and College Towns: A Typology of the US Metropolitan Geography of Higher Education,” published in Urban Affairs Review, Ehlenz, alongside her co-author, Sarah Mawhorter from the University of Southern California, presents a novel framework to better understand the different configurations of higher education institution metropolitan areas.

“It's a really important concept that a university like ASU is contributing to the economic growth of the Phoenix region, but we can't assume that Phoenix and some other college town, like in Alabama, have the same power,” Ehlenz said. “The things that they offer are different, their size is different, and I think you need to know that otherwise, you make assumptions. It's really hard to go forward with university and place-related research without understanding first, specifically, how those contexts vary.”

Filling in the data gap

Historically, the role of higher education institutions has either been studied at a macro level with the focus on the knowledge economy characterizing higher education institutions as one “monolithic sector,” with no differentiation between the influence large institutions have versus smaller liberal arts colleges; or on a micro level, focusing on an individual institution and individual student access and opportunity. Ehlenz and Mawhorter saw this void as a research opportunity.

Harvard University. Photo courtesy of Depositphotos.com

Ehlenz explains that a place like Boston, which is home to "elite" institutions including Harvard, MIT, Boston College, Tufts University and more, is influenced differently by its local universities than a place like Austin, Texas, would be influenced by University of Texas, Austin as it's the only major university there. But the nuances of how those education configurations differ, and where different configurations exist spatially across the U.S. has never been quantified and are not yet fully understood.

“We weren't just looking at an individual university, we're saying that in a metro, what's the constellation of higher education? Is it just one big institution? Is it one big institution and a few small ones? Is it a bunch of elite ones all together? Is Boston truly different from Michigan from Austin etc. and how?” Ehlenz said. “No one has ever touched this and so it was a huge undertaking.”

Tearing the data apart

Using location and institutional data, Ehlenz and Mawhorter analyzed more than 2,000 U.S. four-year institutions and their corresponding metro-level clusters against a framework of seven factors: the number of institutions in a metro, the number of students, the dominance of a single university, diversity of education offerings, admission selectivity, student levels (i.e., share of undergraduate versus graduate students) and graduation rates.

The researchers were then able to categorize higher education metros into two main classes: higher education centers and college towns, and within that identify a total of six distinct types of higher education metros in the U.S.:

- Super centers.

- Major centers.

- Minor centers.

- Strong college towns.

- Multi-college towns.

- Weak college towns.

“Super centers, major centers and minor centers were all metros that have multiple institutions but had different scales and sizes; super centers and major centers were education-rich with a diversity of institutions and opportunities; and strong college towns, multi-college towns and weak college towns, all characteristically were dominated by a single university, although a multi-college town also had a few smaller ones,” Ehlenz said.

Strong college towns and weak college towns both relied on a single institution. Differentiating them came down to the strength of the institution’s graduation rate and its relative accessibility in terms of selectivity.

Data-driven insights on interplay between place and higher education

Examining higher education institutions under this new lens, Ehlenz and Mawhorter exposed some stark differences in the composition between metros with many institutions — higher education centers — versus metros commonly centered around a single institution — college towns.

“The graduation rates you see in super centers, the biggest most diverse metro areas with respect to higher education, are 62% almost 63%, which is above the national average and there are pretty strong graduation rates for major centers as well,” Ehlenz said. “But if you look at the minor centers and the weak college towns, it’s not great, graduation rates are below 45%, so you see a quality difference between these places.”

Ehlenz also notes that from their research they have a richer understanding that in the U.S. the metropolitan geography of higher education is lopsided.

High-quality universities are heavily concentrated in super and major centers, which account for only a quarter of all higher education metros, and scattered throughout multi-college and strong college towns, while, in contrast, minor centers and weak college towns are more ubiquitous amounting to 50% of all metros, but offer relatively few educational resources.

“If you look at the percent of all metros in the U.S. by type, super centers are so successful, they're really big, really strong but only 5% of all the metros qualify as that,” Ehlenz said. “Whereas 30% of all the metros in the U.S. are weak college towns, which means that there's really a different context.”

When mapped spatially, Ehlenz and Mawhorter found that regional patterns of higher education metros corresponded with the ongoing dynamics of urban prosperity and decline in some ways; in others, they go against the grain.

Many of the largest super and major centers are located in long-established metros along the east and west coasts, largely reflecting the metropolitan geography of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when many of the nation’s higher education institutions were founded.

College towns are widespread throughout the Midwest, South and West. Minor centers and weak college towns share some geographic similarities and are both most prevalent in the South, with additional clusters in legacy city metros. A handful of minor centers are located within the Pacific Northwest, while weak college towns have a presence in Midwestern and Western states.

Ehlenz says this paints a picture of just how unevenly higher educational resources are distributed throughout the U.S.

“There's a whole bunch of these weak college towns and minor centers in the south where if you live in one of these states, like Georgia for example, unless you are competitive enough to qualify for admission to an institution in Atlanta, there's a lot fewer choices for you elsewhere and remain in-state,” Ehlenz said. “And these other schools around it don't have particularly good graduation rates either so it becomes sort of a concern that if you aren't willing to travel out of state for any number of reasons, you have fewer options.”

Moving forward

Much remains to be learned about metropolitan geography of higher education, but with this research, Ehlenz and Mawhorter hope to continue to enable new perspectives about the spatial nature of higher education in the U.S., and provide valuable information to city decision-makers and education administrators to support everything from resource allocation to future city planning to education partnerships and coalitions.

“Having this understanding of the more detailed picture about who is in your region and what that means really helps be a bit more specific about what your opportunities are, what your challenges may be and it helps everybody at the table have a clear picture of who they are,” Ehlenz said.

In future studies, Ehlenz and Mawhorter plan to build upon this research to further study student housing around universities and the impacts students have on local housing markets, in addition to studying the long-term opportunities and challenges for students to access higher education from different points around the country.

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU alum's humanities background led to fulfilling job with the governor's office

As a student, Arizona State University alumna Sambo Dul was a triple major in Spanish, political science and economics. After…

ASU English professor directs new Native play 'Antíkoni'

Over the last three years, Madeline Sayet toured the United States to tell her story in the autobiographical solo-…

ASU student finds connection to his family's history in dance archives

First-year graduate student Garrett Keeto was visiting the Cross-Cultural Dance Resources Collections at Arizona State University…