A funny thing happens when you grow accustomed to something in your life. No matter how wonderous or necessary, when it’s always there, you can start to take it for granted.

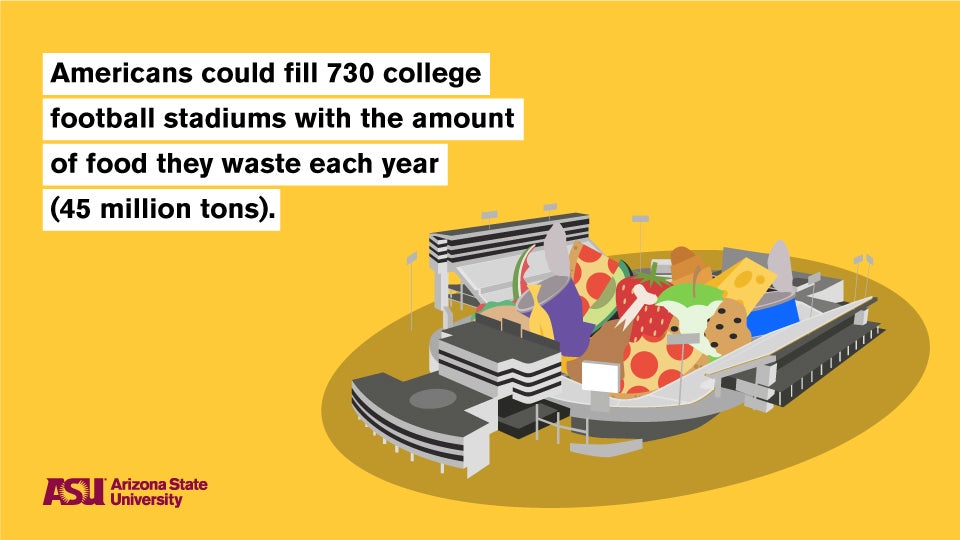

In the United States, where food is relatively easy to come by for most of the population, roughly $165 billion worth of it is wasted every year. That’s enough to fill 730 college football stadiums. And of the food that is wasted, the majority of it is at the household level.

“In a consumer-based culture, food can become easily devalued, especially when it's relatively cheap, as it is in the U.S., for the most part. And that ends up being a driver for food waste,” said Chris Wharton, assistant dean of innovation and strategic initiatives at Arizona State University's College of Health Solutions.

“But if you can show people how much they're wasting and what that means in terms of dollars and cents or lost opportunities for their kids to eat nutritious fruits and vegetables, then you have put value back in the food, and that could potentially drive down food waste.”

Wharton and colleagues recently published a study on the subject in the journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling that employed a values-based intervention in an attempt to reduce household food waste in 53 families in the Phoenix area. The study was funded by a $100,000 grant from Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions in partnership with the city of Phoenix.

Over the course of five weeks, the families that participated in the study were given instructions to read and view different educational material each week that focused on such topics as proper food storage and how to decipher expiration dates. Along with each week’s topic, the educational material also highlighted three values commonly associated with food: cost, health and environmental impact.

“Food waste is as much about the knowledge and the skills needed to reduce it as it is about the values we associate with the food that we buy,” Wharton said.

At the end of each week, participants weighed and logged how much food waste they had accumulated using a clear plastic bin to store the waste and a food-grade scale to weigh it.

“That was one of the novelties of the study, because that type of objective measurement hasn't really been employed before,” Wharton said. “Food waste — like so many other things that we throw out every day, like plastic — it just goes into this magic bucket, the trash can, and it just disappears. But if you can see it, then it starts to tell you something about what it means for that to accumulate, day to day, week to week, month to month, year to year.”

In fact, in qualitative data obtained from participants’ exit interviews following the study, several families reported that watching their food waste build up in the clear bin acted as a sort of feedback mechanism that prompted them, and even their kids, to want to waste less.

The results of the study showed that the intervention was successful in reducing the families’ food waste by an average of 28%. And in a follow-up measurement taken two weeks after the intervention, researchers noted a slight increase in food waste from the families’ postintervention percentage, but still an overall significantly lower percentage of food waste than their baseline amount, measured before the intervention.

READ MORE: 5 tips for reducing food waste and saving money

While those results are statistically significant, the study only scratched the surface of understanding the values we associate with food and how they influence food waste behavior. Going forward, Wharton and his colleagues want to learn more about that in order to develop a predictive model to improve future interventions.

“The approach to revaluate food by trying to attach it to concerns about the environment or health or finances played out interestingly, because different participants found different things more or less important, so it's not totally clear yet what all the drivers of food waste are amongst individuals,” he said.

“There's some sense (according to research) that the elderly may waste a little bit less than younger generations or that wealthier families waste a little bit more than less wealthy families. But there's just not any real consensus in the literature on what predisposes people to waste more or less. There are lots of factors that I think could be really important, like culture, emotions and habitation. And if we can figure out what those are, we can develop better interventions.”

Wharton encourages any families interested in reducing their own food waste to visit the website where the same educational materials used by study participants are accessible to the general public.

“Certainly any family can do this,” he said. “It just takes a little initiative."

Illustrations and top animation by Alex Cabrera/ASU Media Relations and Strategic Communications

More Health and medicine

ASU, Mayo Clinic forge new health innovation program

Arizona State University is on a mission to drive innovations that will help people lead healthier lives and empower health care professionals to develop novel new health solutions. As part of that…

Innovative, fast-moving ventures emerge from Mayo Clinic and ASU summer residency program

By Georgann YaraIn a batting cage transformed into a custom pitching lab, tricked out with the latest in sports technology, Charles Leddon and his Mayo Clinic research teammates scrutinize the…

Is ‘U-shaped happiness’ universal?

A theory that’s been around for more than a decade describes a person’s subjective well-being — or “happiness” — as having a U-shape throughout the course of one’s life. If plotted on a graph, the…