In the U.S., it’s “the enemy of the people.” In Mexico, it’s the “prensa fifi.” And “fake news” is a term of attack against media outlets that crosses the border — as does the problem of political polarization.

Many countries around the world find themselves in a contradictory moment: As we confront a pandemic, economic crises and a total reconstruction of our “normal,” brave, rigorous and transparent journalism is more crucial than ever. Yet at the same time, political polarization, the toxic environment on many social media platforms, and the failures embedded within the traditional media business model threaten to discredit and imperil the industry as a whole.

How can we restore confidence in journalism? What’s the future for the idea of shared narratives and objective information?

Those were central question in Arizona State University’s most recent Convergence Lab event, held July 16 in conjunction with the journalism program of Mexico’s prestigious Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE). Convergence Lab, an events and ideas journalism series, seeks to connect the ASU community with partners in Mexico to consider shared challenges and opportunities.

The challenges of political polarization and journalism in both countries are distinct in many ways, but they also reflect each other in several aspects, said Andrés Martinez, a professor of practice at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and the editorial director of Future Tense.

Media outlets in both countries, for example, have witnessed what Martinez — also a columnist for Reforma’s Mexico Today and a former editorial board member of the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, where he now regularly contributes — called a “perfect storm” of revolutionizing factors.

“The arrival of the internet revolution opens spaces, democratizes journalism, but at the same time, it does break the old business model,” he said. Combine that with the overall polarization of culture and society, Martinez said, and we find ourselves in a place where “journalism, without wanting to, has turned into a political protagonist.”

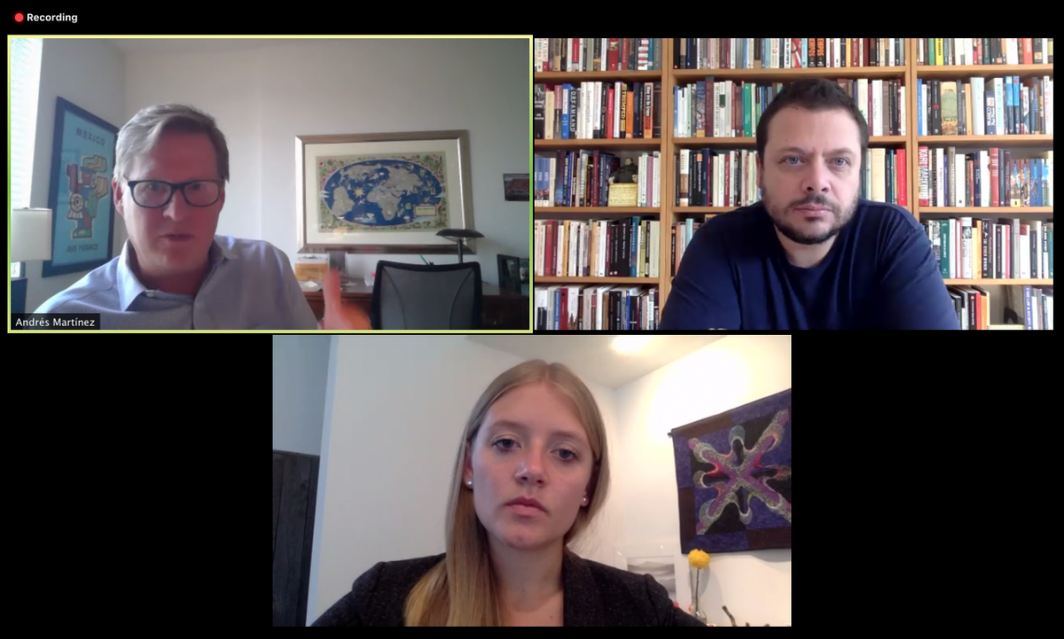

Mia Armstrong (bottom), coordinator of ASU's Convergence Lab, poses audience questions to Carlos Bravo Regidor, right, and Andrés Martinez in an online conversation held July 16 about the challenges of political polarization in Mexico and the U.S.

In Mexico and globally, said Carlos Bravo Regidor, director of Periodismo CIDE, they’ve seen increased fragmentation of audiences. The rise of new technologies and business models has led to a media environment in which “the problem isn’t that there are some very strict, forceful gatekeepers, but rather that there are no gatekeepers,” said Bravo, who is also a columnist in Mexican media outlets including Expansión, Reforma and Gatopardo.

As journalism and other institutions have democratized, “in a way, they break the center, the common ground. And what’s left are just fragments, which begin to perhaps resettle themselves more in the extremes, rather than in the space of traditional consensus,” Bravo concluded.

Before the rise of social media and the digitization of journalism — what Bravo calls the “dictatorship of the click” — editors and journalists had “the privilege of not knowing which articles were the most read,” Martinez said. That meant that if you wanted to write an editorial on a topic that you considered important, but which you knew might be boring for the reader, you would do it, because the reader would buy the paper regardless. Now that calculus and those incentives have changed, he said.

To add another layer, both the U.S. and Mexico are now led by presidents that have generally antagonistic, though complex, relationships with the press. “They like the media, but they don’t like journalism,” Bravo explained.

While they share some common threads, the threats to journalists and free press faced in Mexico versus the U.S. are in many ways incomparable.

In the U.S., for example, “the Trump administration has stepped up prosecutions of news sources, interfered in the business of media owners, harassed journalists crossing U.S. borders, and empowered foreign leaders to restrict their own media,” wrote Leonard Downie, the former executive editor of the Washington Post and a Cronkite professor, in a recent Committee to Protect Journalists report.

In Mexico, though, the threats are more concrete, more deadly, and have a wider variety of perpetrators, including organized crime. Between 1992 and 2020, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, at least 54 journalists have been killed in Mexico, and 14 have gone missing. So far this year, three journalists have been killed in connection with their work in Mexico, according to Reporters Without Borders.

These threats make doing journalism in Mexico, in many ways, a daily battle for survival, even before considering what one audience member called the “a priori disqualification” of journalists by government discourse.

This all raises questions in both countries about the role of objectivity in journalism — what it is and how it can and should be practiced.

For Bravo, “objectivity isn’t a position, it’s a method.” Treating objectivity as a method means recognizing biases, and then working to ensure that those biases don’t impede our process of seeking the most honest version of the truth.

“What defines journalism is following a method, and that method opens up a certain space — imperfect, contested — to be able to learn the truth, the reality, the facts,” he said.

“We should be activists for the truth,” agreed Martinez.

In practice, treating objectivity as a method means diversifying sources, corroborating, and situating events and their implications in a broader context, the two agreed.

“Journalism, in my opinion, its place is to take sides, but to take the side of the facts. And in a circumstance of so much change … so much polarization, suddenly it takes a lot of work to defend something as basic as that,” said Bravo.

Written by Mia Armstrong. Top image courtesy of Pixabay.

More Law, journalism and politics

How to watch an election

Every election night, adrenaline pumps through newsrooms across the country as journalists take the pulse of democracy. We gathered three veteran reporters — each of them faculty at the Walter…

Law experts, students gather to celebrate ASU Indian Legal Program

Although she's achieved much in Washington, D.C., Mikaela Bledsoe Downes’ education is bringing her closer to her intended destination — returning home to the Winnebago tribe in Nebraska with her…

ASU Law to honor Africa’s first elected female head of state with 2025 O’Connor Justice Prize

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first democratically elected female head of state in Africa, has been named the 10th recipient of the O’Connor Justice Prize.The award,…