ASU professor says clear messaging needed for COVID-19 pandemic

Associate Professor Bradley Adame

As the death toll from the coronavirus continues to rise, Americans in search of information are getting mixed messages from both the medical and political communities.

Doctors on television say to stay at home. President Donald Trump tweets that we need to reopen businesses to get the economy going. Governors generate their own edicts that can contradict those in neighboring states or their state's mayors.

Experts are concerned that these conflicting and confusing messages are providing people with a green light to interpret government guidelines at their own discretion.

“Conflicting government messages have only exacerbated the widespread confusion about this worldwide pandemic,” said Arizona State University Associate Professor Bradley Adame, who studies crisis communication at the Hugh Downs School of Human Communication.

“The most important ingredient in messaging is consistency from our elected officials, from the top down,” Adame said.

This month Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego voiced her concerns about mixed messaging when it comes to the coronavirus.

A tweet from Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego on mixed messaging

"We were one of the last states to go to a stay-at-home order and one of the first to come out. I'm concerned that people are getting mixed messages about how serious this is," Gallego said on CNN. “When I talk to public health professionals and our doctors and nurses, they tell me they are deeply concerned. They are worried that the public thinks COVID-19 is something we have defeated.”

Adame says inconsistent messaging makes it easier for individuals to either ignore what they hear, or to pick and choose the information that best suits their individual desires.

“If I'm in California and I'm under strict lockdown and I see people in Texas who are living lives normally, it might make me question the validity and the veracity of those orders,” Adame said. “I might ask myself, ‘Why am I being ordered to stay at home when other people are free to do what they want?’”

The collective good

Adame says not since World War II have we had to take such drastic measures and change how we live.

"Just like during the war, there is a need for a concerted national effort. That's why the consistency of messaging comes into play. If you're getting the same message from multiple agencies, not only does that boost the credibility of that message, but it also starts to communicate the importance of abiding by those regulations, such as social distancing.”

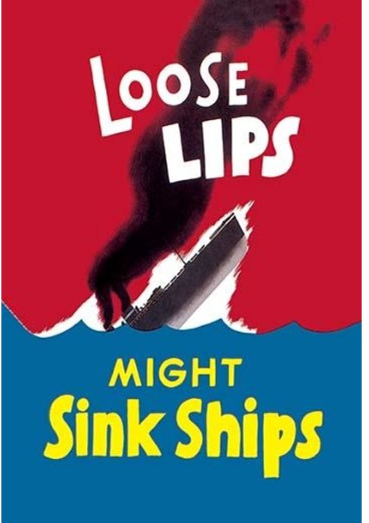

This type of poster was part of a general campaign of American propaganda during World War II to advise servicemen and other citizens to avoid careless talk that might undermine the war effort.

Adame points to the propaganda the U.S. government developed during World War II that showed how our individual actions added to the overall war effort.

“The government asked us to plant a victory garden and not spread rumors. The messaging was focused on individual behavior that ultimately added to the collective good. That type of messaging strategy would be helpful now to mitigate the spread of this virus.”

To convince people to cooperate, Adame says politicians need to communicate a clear sense of urgency. “Just like during the war, they need to show how we’re interconnected. The coronavirus proves this.”

Adame has studied social messaging campaigns the government has employed to warn of natural hazards — hurricanes, tornadoes and earthquakes — to motivate American citizens to prepare, advise them of their hazard risk, and inform them of specific behaviors.

He studies how people process risk information, specifically the decisions they make that either puts them at greater risk or mitigates their risk.

“People aren't always aware of their actual risk of suffering the consequences. It’s the old argument that it will never happen to me.”

As an example, Adame points to those living in Oklahoma ‘s “Tornado Alley.”

“People there might say, ‘Well, if my house gets blown off the foundation and I get sucked away to Oz, like Dorothy, then what good is a preparedness kit going to do for me?’ And for those people they're correct.”

But for most people in tornado situations, Adame says they might lose power, or lose water for a few days, or maybe part of their roof gets destroyed, but they don't get “blown away to Oz.”

“They still need things like water and food. They need to have those things on hand so they don't have to rush out and go get them. They can hunker down, stay safe and perhaps help those people next door to you who maybe did lose their roof.”

Adame admits that when it comes to the coronavirus pandemic, getting people to understand the risks is a huge factor for them to understand the actual benefit of behaviors that might help them survive, such as wearing a mask in public, or social distancing.

“If there are very few reported cases where you live, or you don’t know anyone who has the virus, you might think it’s not an issue for you,” he said.

Therefore, Adame says the goal of government should be to craft messages that explain that the virus is a real threat, and there are things that you should do to ensure or to at least enhance your probability of surviving.

“As the frequency and magnitude of hazards, including pandemics, continue to grow, citizens will increasingly find themselves at risk of suffering consequences from these events,” Adame said.

“This demonstrates the relevance of communication research and the potential contributions communication theory can make in developing effective messages that both inform audiences and persuade them to prep."

More Health and medicine

College of Health Solutions medical nutrition student aims to give back to her Navajo community

As Miss Navajo Nation, Amy N. Begaye worked to improve lives in her community by raising awareness about STEM education and…

Linguistics work could improve doctor-patient communications in Philippines, beyond

When Peter Torres traveled to Mapúa University in the Philippines over the summer, he was shocked to see a billboard promoting…

Turning data into knowledge: How Health Observatory at ASU aims to educate public

This is how David Engelthaler described his first couple of months on the job as executive director of the Health Observatory at…