ASU researcher explores harmful species on a global scale

Photo courtesy of Pixabay.

If you’ve spent time in national parks or state recreational areas, you’ve likely seen warnings about the spread of invasive species. From inspection checkpoints for cars and boats to restrictions on bringing firewood and fruit across state lines, officials are working to prevent outbreaks of pests, parasites and diseases, which can wreak havoc on entire ecosystems.

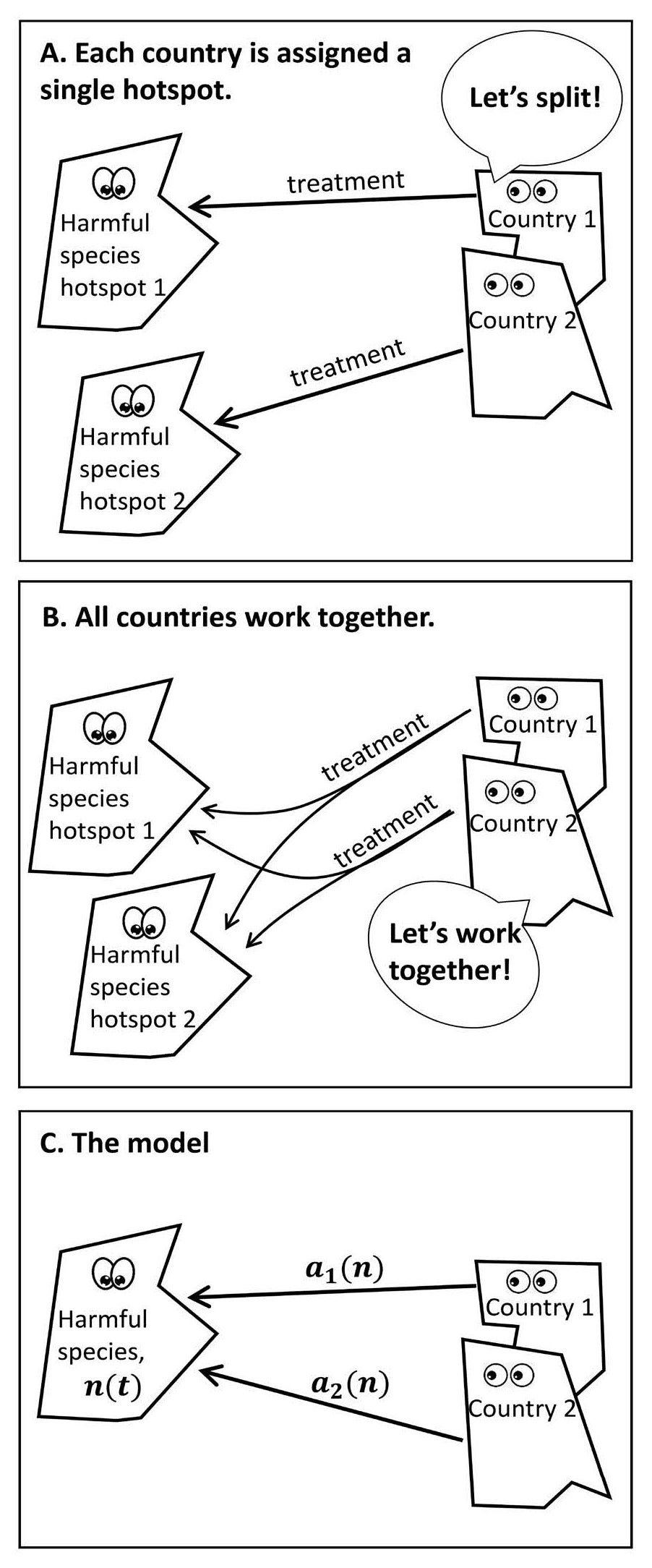

Most examples are relatively small — impacting one localized region. But policymakers face difficult choices when vast numbers of invasive species and other kinds of harmful species affect multiple countries. Think of species like locusts and starlings or even diseases like smallpox and COVID-19. Should countries work together in multiple hot spots or divide the land between them for treatment?

Adam Lampert, an assistant professor with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University, turned to mathematical modeling for answers. His findings, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that sometimes a “divide and conquer” approach is better, while in other situations it is more effective to cooperate in several locations.

“If you want to eradicate the harmful species, or reduce its abundance rapidly, then you may want to split the duties of the agents,” Lampert said. “If you want to control it, and keep it at a low level for prolonged periods, then working together becomes important.”

To reach this conclusion, Lampert developed a mathematical model based on game theory, which attempts to predict the behavior of players in a scenario. His model compares several scenarios on the assumption that each party will work in their own best interest.

Two countries would like to treat a harmful species population in two hot spots. They may decide to divide things up, such that each country works only in its designated hot spot (A), or they may work together in both hotspots (B). To determine the best option, Lampert developed a mathematical model (C) that compares them.

Within the context of invasive species, this means the model considers the most likely action each country will take. Even when working cooperatively, each country will presumably act in ways that promote the most socially desirable outcome for its own citizens.

But that’s only part of the equation. Given the findings, if the goal of either controlling or eradicating determines the best approach, then a key question is when to focus on eradicating or merely controlling a harmful species outbreak.

Lampert identified three factors to determine if the species should be controlled or eradicated: the annual cost of maintaining the population, the natural growth rate of the harmful species, and its response to the treatment. In general, eradication is more likely when the cost of treatment does not depend on the density of the species.

For example, when treating an invasive insect outbreak, managers cannot target individual bugs. They spray pesticide over a large area as a general treatment method. If some insects survive the first round of spraying, the managers can spray the area again, but it would not be as cost-effective as the first time. In this situation, controlling the invasive species population at a low density is more likely than eradication.

A more targeted approach can be applied if the species can easily be seen. For example, complete eradication of a harmful plant species is plausible, because managers can physically remove each plant.

Given the ongoing spread of novel coronavirus, Lampert shared that we’re seeing a mix of blanketed and targeted control efforts.

“With diseases, you can put a lockdown on the entire country, or a region, and say, ‘OK, nobody goes out,’ and this way you reduce the infection level over time,” he said. “Or you can do some more targeted actions by identifying the people who are sick — and keeping them at home.”

Lampert’s research indicates that most effective control methods to reduce the spread of novel coronavirus require international cooperation. He said it is unlikely that we will be able to completely eradicate the virus, but controlling the spread is necessary for our social welfare and can be accomplished most effectively if countries work together.

Lampert is already working on additional research applying these findings to COVID-19, specifically. In the future, we can expect to see more intensive findings about the spread and control of invasive species, as the issue is not likely to disappear anytime soon.

“The impact of invasive species is a major problem in ecological systems,” Lampert said. “And it’s only becoming more and more prevalent because of globalization.”

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU’s Humanities Institute announces 2024 book award winner

Arizona State University’s Humanities Institute (HI) has announced “The Long Land War: The Global Struggle for…

Retired admiral who spent decades in public service pursuing a degree in social work at ASU

Editor’s note: This story is part of coverage of ASU’s annual Salute to Service.Cari Thomas wore the uniform of the U.S. Coast…

Finding strength in tradition

Growing up in urban environments presents unique struggles for American Indian families. In these crowded and hectic spaces,…