At the beginning of his classes, Arizona State University law Professor Myles Lynk would share the poem “Ithaca” by Constantine Cavafy, reminding students that the long and challenging journey ahead is as much the prize as the destination is.

As you set out for Ithaca

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

And throughout a career that has taken him across the country and beyond, there has been a common thread for Lynk. Whether volunteering in the Pruitt-Igoe housing project of St. Louis, leading social work in Uganda, serving on the White House domestic policy staff during the Carter administration, becoming the first African American partner at Dewey Ballantine LLP or serving as president of the District of Columbia Bar, he has always worked for the greater good.

“My first job after law school was as a law clerk for Judge Damon Keith,” Lynk said. “And he lived the admonition of the great African American lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston, who also taught at Howard Law School, which is, you should use the law for good. And that stuck with me. And my experience as a lawyer in private practice certainly informed my teaching at ASU.”

Lynk’s winding and illustrious career brought him to Arizona State University, and specifically, the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. And as he has always done, he made things better — for colleagues, students and everybody he came in touch with — building an indelible legacy as a leader and ambassador for ASU, greater Phoenix and the local legal community.

May you stop at Phoenician trading stations

Now, after 20 years, Lynk has retired from ASU Law’s full-time faculty, answering a call to return to the nation’s capital to work as the senior assistant disciplinary counsel for appellate litigation in the District of Columbia Office of Disciplinary Counsel, the organization that prosecutes professional misconduct by members of the Washington, D.C., Bar.

“I've taught professional discipline and professional regulation and legal ethics, and this is a real opportunity to apply this expertise to the real world, in real time, to real people,” he said. “And it's sobering.”

Despite the new role, Lynk will remain part of the ASU family, not only as an emeritus professor but also in helping to develop a course on government ethics with ASU’s School of Public Affairs in Washington.

“Although this is an enormous loss for ASU Law, we are thankful for the lasting impact he has made, and happy to know he will continue playing an important role in the legal world,” said ASU Law Dean Douglas Sylvester. “He has been a leader in so many ways at this university, and has always done so with grace and dignity.”

Leadership in the classroom and beyond

Lynk took on a range of critical roles during his 20 years at ASU, during which the law school and university rose to new levels of growth and prestige.

In addition to his full-time faculty role with ASU Law, he also held appointments at various times as an honors faculty fellow in Barrett, The Honors College; as a scholar-in-residence at the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy; as a senior fellow in the Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics; and as a sustainability scientist in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute on Sustainability. Lynk advised University Senate President Helene Ossipov on revisions to an ASU academic policy that addresses relationships between faculty members and students, and wore many hats within the law school, including the dean’s designee for student disciplinary matters and as a faculty adviser to several student organizations.

"Professor Lynk was an integral part of this university for the past two decades, representing ASU in numerous capacities with dignity and professionalism,” ASU President Michael Crow said. “We are thankful for his years of service, and we will miss him immensely."

Lynk was frequently tapped by President Crow, serving from 2004 to 2010 as ASU’s NCAA and Pac-10 (now Pac-12) conference faculty athletics representative, responsible for certifying the academic eligibility of ASU’s intercollegiate student-athletes. He was also a member of President Crow’s academic council, a member of two provost’s Regents’ Professor nomination committees and, most recently, a member of a President’s Professor advisory panel.

In 2005, President Crow tasked Lynk with leading the university’s investigation into the shooting death of a graduate student by an undergraduate student-athlete. This resulted in the “Lynk Report,” which recommended numerous changes to improve campus safety at ASU. Christine Wilkinson, senior vice president and secretary of ASU, worked alongside Lynk on that tragic assignment.

“Among the numerous responsibilities he undertook while at ASU, he was tapped for the faculty athletic representative for ASU,” Wilkinson said. “During his tenure, we both worked very closely together on responses to a very difficult circumstance as well as leading in the development of student-athlete reforms that remain in place today. He was, and still is, very thoughtful in his deliberations, insightful in his recommendations, and a first-class ambassador for ASU.”

Lynk also journeyed beyond ASU during his time there, serving as a visiting professor at Duke University School of Law in 2010 and as a visitor to the University of Cambridge Faculty of Law while he was a visiting fellow at Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 2014, researching the differences between how the U.S. and the U.K. regulate the legal profession. He has also published in the Professional Lawyer journal; the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics; and Human Rights magazine.

But Lynk made perhaps his biggest impact in the classroom.

And may you visit many Egyptian cities

to learn and go on learning from their scholars.

“He was very attentive about trying to answer questions as in-depth as possible,” former student Jordan Brunner said. “He spoke to us, not at us.”

Recent graduate Sarah Randolph took Lynk’s Professional Responsibility class during her 2L year.

“He, more than any professor I had, prepared me for the realities of practice, because he helped me understand the differences between studying from a book and actually living the situation,” she said. “Particularly with (the class) Professional Responsibility. It seems very black and white when you read the rules, but he comes up with hypotheticals that are not so clear and forces you to really think about how you’d handle the gray situations.”

The next semester, Randolph served as his teaching assistant, and she later took his Business Organizations class. Now a licensed attorney, she says the lessons she learned on professional responsibility have already helped her tremendously in practice.

Vanessa Kubota, current 2L student at ASU Law.

Vanessa Kubota, a second-year ASU Law student, says Lynk has a way of teaching that keeps classes interesting and exciting.

“When I tell people that Professional Responsibility was one of my favorite classes in law school, they usually seem surprised,” Kubota said. “The first thing most students say is, ‘PR was totally confusing and extremely uninteresting.’ My classmates and I would all respond, ‘You didn't have it with Professor Lynk.’”

Although students are naturally focused on specific goals — getting an "A" in a class, graduating from law school, passing the bar exam — Lynk always tried to keep them in the moment, not too fixated on what lies ahead.

“In my classes, when I talked to students at the beginning of the year, I would say it's a voyage,” he said. “And I reference the poem ‘Ithaca.’ That it’s not the destination, it's the voyage that counts.”

Liam Welch, a third-year ASU Law student, says he literally begged to serve as Lynk’s teaching assistant after taking his class. He landed the role, and when Lynk had to miss the second class of the semester, he asked Welch to take his place.

“It was a huge compliment, but a daunting task,” said Welch, adding that he might have put more effort into teaching that class than he did for some of his assignments as a student. “While I was touched by his confidence in me, I was overwhelmed by the enormous shoes I had to fill.”

Not wanting to belie that confidence, Welch said, can lift a student to new heights.

“He has a gift that inspires his students to always strive to do better,” he said. “When I sat for the MPRE, I was terrified of failing. Not because I would have had to retake it, or pay another fee. Rather, I was horrified of the prospect of letting Professor Lynk down. He had demonstrated confidence in my abilities and knowledge of professional responsibility by entrusting his class to me. So, failure was not an option. When I received my passing score, I was so excited that I was compelled to email Professor Lynk right away — I think it was around midnight — to let him know that his confidence in me was justified.”

2017 ASU Law graduate Jennifer Murphey said she, too, was driven to succeed by Lynk’s unwavering belief in her.

“Professor Lynk is genuinely invested in his students’ success,” she said. “He is a wonderful mentor with a unique ability to provide constructive criticism in a way that made me believe in myself and believe I could do better. He pushed me to do better because he genuinely believed I could do better.”

She added that Lynk contributes to the integrity of the entire legal community with each student he mentors. “He uniquely instills self-confidence in his students, which is directly intertwined with capacity.”

Former student Jay Calhoun says upon her arrival at ASU Law, she walked to Lynk’s office, knocked on the door and introduced herself, having been impressed with Lynk’s experience practicing business law. Her admiration only grew from there.

“Every lucky student has a great teacher who inspires her,” Calhoun said. “I was fortunate to have the inspiration of Professor Lynk. William Arthur Ward said it best: ‘The mediocre teacher tells. The good teacher explains. The superior teacher demonstrates. The great teacher inspires.’ Professor Lynk inspired me. There is no list of adjectives to do Professor Lynk justice. I am lucky that I got to know Professor Lynk over the past 20 years and I admire his consummate professionalism, dedication to and service to the better of the legal profession and those who practice it.”

Keep Ithaca always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

“What I love about Professor Lynk is the way he teaches students to approach the model rules — not as inviolable regulations, but as works in progress that are perpetually being improved and that are susceptible to amendments and proposed suggestions,” Kubota said. “Moreover, Professor Lynk makes you feel like he will be your mentor for life. He really cares about his students and will be a resource for those who rely on him, for mentorship and instruction.”

Randolph, too, recognized that Lynk genuinely cared about his students, recalling a time when she was struggling to juggle parenting and law school.

“During one of his classes, I had a 4-year-old and I was eight months pregnant and absolutely exhausted,” she said. “He met with me after class and reviewed topics that I didn’t understand. He never once got annoyed that he had to repeat himself, he simply understood that my brain was fried and tired and at capacity and he knew that I just needed to hear the information one more time. That kind of personalized approach to teaching makes him one of the very best.”

Current ASU Law MSLB student Heather Udowitch.

In the past year, Lynk served as the thesis director for Heather Udowitch, then a Barrett, The Honors College student who is now a student in ASU Law’s Master of Sports Law and Business program.

“His guidance, support and intelligence was unparalleled,” she said. “I cherished my time with Professor Lynk, as I learned how to write with intent, speak directly with confidence, and maintain a keen demeanor at all times. More importantly, I learned how impactful these skills are in order to be a transformative leader. It was a true honor and privilege to work with Professor Lynk.”

Admired and respected by students and colleagues alike, Lynk received the College of Law Alumni Association’s Faculty of the Year Award in 2010. Mixing dry humor with a dignified presence, he kept students smiling while commanding their respect.

“I was so very sad to hear that he is retiring from teaching, because the students that come after this will be missing out of learning from one of the best and brightest minds,” Randolph said. “But I am very happy for him and his next steps in his career.”

Lessons that transcend law school

As students will attest, Lynk did not just teach law. He also taught about life. And those lessons continued long after graduation.

Former student Tammie Curtis has known Lynk for nearly 20 years.

“Within those 20 years, I have not only been fortunate to call him a former law professor but also privileged and honored to call him a mentor in career and life,” she said. “I still remember the day he bid goodbye to those of us who were bound for graduation in the next few days as though it was yesterday.”

She recalls Lynk stressing the importance of balance, noting that many of the students would be setting out to achieve three things: financial success, a gratifying career and a good family life. He told the students success in one of those areas could come at the expense of the other two, and that they must remain mindful of their top priorities.

“From time to time, I have been successful in achieving wealth or career, but never at the same time, as I realize that it will be at the cost of losing my greatest achievement: my family,” Curtis said. “There is not a day that goes by since then, in my career and life, that I have not reflected on Professor Lynk's message.”

Calhoun recalls her initial meeting with Lynk, when she showed up at his office as a first-year student. He was gracious and insightful then, and continues to offer guidance to this day.

“About a decade ago, I worked for a firm that was experiencing some ethical problems,” she said. “I went to Professor Lynk in confidence to discuss the situation and my options, and he gave me the advice I needed to hear but wanted to avoid. I left the firm, started my own practice and have been able to obtain free ethics advice from Professor Lynk ever since.”

Curtis, too, has continued turning to Lynk for advice, conferring with him throughout her career.

“With every meeting, I not only have a mentor but a friend who cares about and respects the person I am, and the circumstance I am in,” she said.

And the success she has had in her career, she says, is directly attributable to her family and her legal training at ASU Law. “And to inspiring and irreplaceable individuals like Professor Lynk, who the almighty has gifted with intelligence, integrity, compassion and ability to inspire the next generation of legal innovators.”

Welch says it’s difficult to put into words what Lynk has meant to him and so many other students: “Suffice it to say, I would follow that man to the gates of Mordor. And beyond.”

A role model for African Americans

Although Lynk has seen improvements throughout his career, the legal industry is still plagued by a lack of diversity. According to the American Bar Association, 85% of resident active attorneys in the U.S. identify as Caucasian.

That can dissuade some minority students from pursuing a law career. They may be uncertain of how they will fit in or be perceived. But Lynk says character will always win out.

“I’m not going to say that stereotyping doesn't happen, but you always have a chance by what you do and by who you are to transcend those stereotypes,” he said. “Your goal is to be the best you that you can be. And if you do that, stereotypes fall away.”

Former ASU Law student Jordan Brunner at 2018 spring convocation ceremonies.

Lynk served as faculty adviser for the John P. Morris Black Law Students Association. Ijana Harris was president of the group, and says Lynk was heavily involved, helping mentor students from their first year to graduation and beyond.

“Professor Lynk makes it a point to be available to current and former students to provide professional and life advice,” she said. “He challenges students to think critically and to work hard to make larger societal impacts. I have always valued my relationship with him, and appreciate the guidance he has provided both in law school and beyond.”

Jordan Brunner served as vice president of the Black Law Students Association and says Lynk provided indispensable leadership, assisting with everything from big-picture issues to the nitty-gritty details.

“I was rewriting the constitution for our group, and he went through my draft very carefully with a red pen, helping to clean up grammar and make it clearer,” Brunner said. “He was a great mentor, and I knew I could walk into his office anytime.”

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

wild Poseidon – you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Lynk said it’s important for law schools and the legal industry to keep expanding access, and for students to seize those opportunities.

“I hope to see more minority students coming through the pipeline, coming into law school, graduating, joining the bar, getting on the bench, getting elected, going into government and business, and doing well while working for the greater good,” he said.

Lynk also served as the faculty adviser to a number of other ASU student organizations, including the Sports and Entertainment Law Journal, which dedicated its Volume 5 to Lynk, “for his profound dedication to all of his students.”

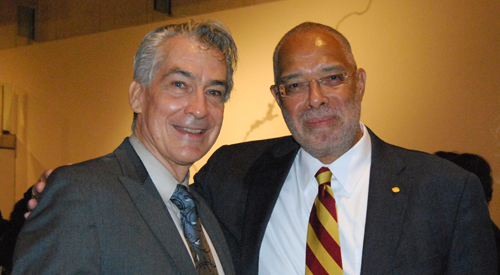

Professor Myles Lynk and Judge Cecil B. Patterson in 2017.

Lynk remembers being welcomed into the ASU and Arizona legal community by, among others, professors Charles Calleros and Jonathon Rose, and by Judge Cecil Patterson, an ASU Law graduate who, in 1995, became the first African American to serve as an appellate court judge in Arizona when he was selected to serve on the Arizona Court of Appeals.

“When my family arrived here in late 1999, Professor Calleros and his family were incredibly generous with their time to welcome them into the Arizona community. In 2000, Professor Rose went out of his way to organize a lunch for me to meet judges and lawyers in the community, and so did Judge Patterson, who organized a get together for my wife and I to meet other African American lawyers in the community,” Lynk said. “One of Cecil’s concerns was that I see this as a diverse community. He didn’t want me to look around and think that I needed to leave.”

The journey continues

Lynk did not leave. Instead, he spent the next 20 years here, working to bring out the best in ASU and the Phoenix region.

He is proud of what has been accomplished at ASU Law and the reputation the school has achieved.

“My advice to a student applying to law school would be look at the value proposition you get from different law schools,” he said. “The value proposition you get at ASU Law is very high. Your tuition is not exceptionally high, and the quality of instruction is very high, the quality of the faculty is very high, the quality of your fellow students is very high. If you're not from the Southwest, living in the Southwest is a unique experience. If you are from the Southwest and Arizona and you intend to practice here, going to law school here is a professional advantage.”

Professors Myles Lynk and Charles Calleros at the Lifetime Achievement Award event presented by the Arizona Black Bar Association in 2015.

During his time in the Valley of the Sun, Lynk took leadership roles at the university and in service to the legal community. He co-chaired the Arizona State Bar’s Task Force on Multijurisdictional Practice, taught in the State Bar’s Bar Leadership Institute, was appointed by U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist to serve two terms on the Civil Rules Advisory Committee of the Judicial Conference of the United States, was elected to the governing Council of the American Law Institute and chaired the American Bar Association’s Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice and Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility, among other professional service. In his work with students, he invoked critical-thinking and broadened horizons. He fostered appreciation for the journey – the journey through classes, the journey through law school, the journey through careers, the journey through life.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaca to make you rich.

And now, it is time to leave. To return to Washington, D.C., for the next stage of his voyage.

“It just was a challenge I didn't feel I could say no to,” he said. “I felt if I said no, I'd be closing a door. And if I said yes, I'd be going through the door. Was there some anxiety? Of course. But there was also some excitement. And I thought, ultimately it felt good to be excited and it felt good to be able to apply in practice what I had taught in law school.”

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

angry Poseidon – don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement stirs your spirit and your body.

Top photo: ASU Law Professor Myles Lynk is pictured at the 2019 Sandra Day O'Connor Institute's Constitution Day Town Hall event.

More Law, journalism and politics

Native Vote works to ensure the right to vote for Arizona's Native Americans

The Navajo Nation is in a remote area of northeastern Arizona, far away from the hustle of urban life. The 27,400-acre reservation is home to the Canyon de Chelly National Monument and…

New report documents Latinos’ critical roles in AI

According to a new report that traces the important role Latinos are playing in the growth of artificial intelligence technology across the country, Latinos are early adopters of AI.The 2024 Latino…

ASU's Carnegie-Knight News21 project examines the state of American democracy

In the latest project of Carnegie-Knight News21, a national reporting initiative and fellowship headquartered at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication…