Google hosts ASU Mexico Convergence Lab on tech in education

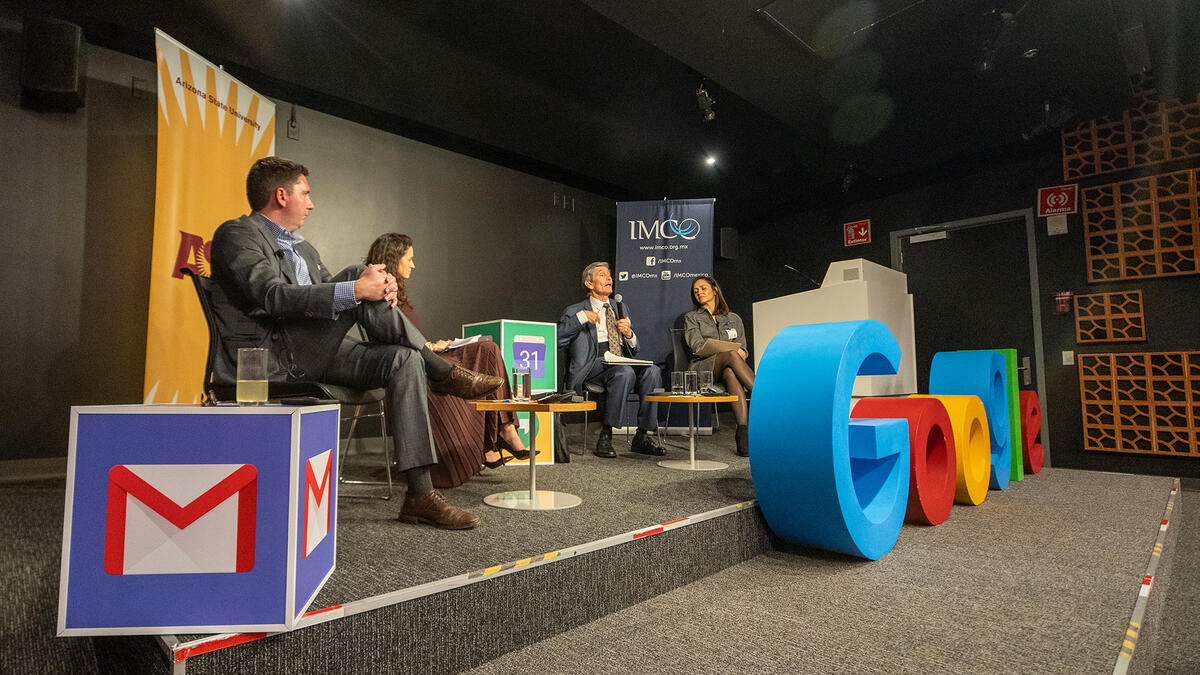

From left to right: Luke Tate, Alexandra Zapata, Rafael Rangel Sostmann and Georgina López Guerra. Photo by Pedro Daniel Uribe.

Watching videos online and answering generic true/false questions. Posting into the void of a discussion forum and expecting little response. Feeling like user No. 237 rather than being acknowledged as an individual student with independent ideas. Spending more time figuring out how to use a new platform than extracting value from its content.

These are the sort of problems that might come to mind when we think of technology in the future of education — when technology is used poorly in the education sector, it can depersonalize and frustrate.

But when educational technology is used well, when technological innovation prioritizes the needs of students and teachers, then its power is transformative.

So how do we get there, to this place where technology meets students where they are and helps them fulfill their full potential?

This was the central question at Arizona State University's latest CDMX Convergence Lab, held on Tuesday at Google’s offices in Mexico City, in collaboration with Google for Education and the prestigious Mexican think tank el Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad (IMCO).

Convergence Lab is the series of quarterly forums and networking receptions ASU hosts in Mexico City to connect faculty to Mexican counterparts and to foster crossborder consideration of shared challenges and opportunities. Previous Convergence Labs have featured Lindy Elkins-Tanton, managing director and co-chair of the ASU Interplanetary Initiative; Kenneth Shropshire, CEO of ASU’s Global Sport Institute; and Enrique Vivoni, associate dean of the Graduate College.

Technology with a purpose

Georgina López Guerra, the founder and director of Continuum, set the stage for the discussion at Google with two questions that should shape the way we think of the future of educational technology: “Education to what end?” and “Technology to what end?”

“For us it’s not about bringing technology just to bring technology,” said Jimena García, the head of Google for Education in Mexico.

García highlighted that back in 2006, ASU was one of the first universities to deploy Google’s G Suite for Education, which uses online tools to empower students and educators and to close global equity gaps in education.

Learning without limits

ASU’s incorporation of technology is based on the university’s mission of supporting universal and lifelong learning, explained Luke Tate, the managing director of ASU’s Office of Applied Innovation and former special assistant for economic mobility to President Barack Obama.

The idea behind universal and lifelong learning, Tate added, is that everyone should be able to access a high-quality education, regardless of where they come from or where they are. Hence ASU’s efforts not only to deploy technology to enhance the education of on-campus students, but also to expand learning opportunities to everyone from refugees and displaced persons to Starbucks employees.

Looking not only to expand its mission to adult populations, the university is also using data to assess the K–12 public education system in Arizona, Tate explained. The goal is to proactively identify, with the use of AI, what kind of support individual students might need in order to make it to college — and then to deliver that support.

Educating for the future

Of course, one of the major challenges in the education space is that an estimated 65% of children will ultimately perform a job that does not yet exist. So how do we prepare students for those jobs?

The answer is to focus education on developing skills, such as the ability to be able to learn for oneself, said Rafael Rangel Sostmann, special adviser to President Michael Crow and the former president of the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, one of the largest and most prestigious universities in Latin America.

“My mission is to educate citizens,” Rangel Sostmann said. “My mission is to educate people who will continue learning their whole lives.”

Rangel Sostmann highlighted that personalized and adaptive education can go a long way in increasing graduation rates.

At ASU, from 2002 to 2017, the first-year freshman retention rate rose from 78% to 87%, and from 2002 to 2013, the four-year graduation rate increased by 85%. ASU is awarding more degrees — 33% more since 2013 — to a more diverse group of students. The number of first-generation students at the university has more than tripled since 2002, and 53% of Arizona freshman in 2018 came from underrepresented populations.

Tate stressed the importance of ASU’s charter commitment to be “measured not by whom it excludes, but by whom it includes and how they succeed” — it’s that promise that drew him to join the university upon leaving the White House. And the smart deployment of new technology, with that question of “to what end” having been answered, is instrumental to deliver on the charter.

Innovating toward inclusion

Alexandra Zapata, the deputy general director of the Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad — which has produced groundbreaking research and policy advocacy to empower citizens’ participation in their children’s education and hold educational institutions more accountable — explained that one of the key challenges to effectively expanding education technology and accessibility in Mexico is overcoming a mindset summarized by the phrase in Spanish “No te pongas creativo,” or “Don’t get creative.”

We need to change from “a generation of parents that told you ‘Don’t get creative’ to one that tells you, ‘How can I help you be more creative?’” she said.

Written by Andres Martinez

More Science and technology

ASU professor shares the science behind making successful New Year's resolutions

Making New Year’s resolutions is easy. Executing them? Not so much.But what if we're going about it all wrong? Does real change…

ASU student-run podcast shares personal stories from the lives of scientists

Everyone has a story.Some are inspirational. Others are cautionary. But most are narratives of a person’s path, sometimes a…

The meteorite effect

By Bret HovellEditor's note: This story is featured in the winter 2025 issue of ASU Thrive.On Nov. 9, 1923, Harvey Nininger saw…