Cannibals. Vampires. Zombies. Parasites that devour you from within.

Whatever abomination prowls your nightmares and sends cold sweat trickling down your spine, nature likely has it beat.

For All Hallows Eve, ASU Now turned to the Social Insect Research Group in the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University, where connoisseurs of the insect world like postdoctoral research fellow Christina Kwapich and PhD candidate Andrew Burchill can tell you about bug behaviors you can’t even imagine.

Let’s take a dive into real horror…

I melt you

Larvae of beetles of the Epomis genus look like a nice little snack for frogs. They’re not. If a frog bites one and decides it don’t like it? Too bad. It’s not letting go. It’s going to eat the frog, and it will be neither quick nor pretty.

The larva is much faster than a frog, and it has huge hooked jaws that won’t budge from its lips, tongue, throat, or wherever it’s seized. Next, it digests the tissue. Strange thing, though – there’s no blood. The larva is secreting enzymes which melt flesh. It’s digesting the frog before it eats it. After a couple of days of this, Mr. Ribbit is so weakened he can’t move. The larva now begins tearing hunks of tissue out of the frog until all that's left is a little pile of bones.

You gonna eat that?

Many ants share food by regurgitation from mouth to mouth. It’s called trophallaxis. Hopefully we won't see that trend popping up like shared plates at hip restaurants.

Dracula ants

Ants regurgitate digested food from babies to adults (the opposite way from how birds do it). Adult Dracula ants (yes, that’s their real name) only get their sustenance from biting their larval sisters and drinking their blood. “However, it doesn't really hurt the larvae, they're just doing their part for the colony,” Burchill said.

This is going to hurt…

A male bed bug will mate with a female by piercing the wall of her body cavity. “His sperm travels through her blood, called hemolymph, to her ovaries!” Kwapich said.

Heads up

Female phorid flies lay their eggs behind the head of an ant. The fly maggot develops inside the ant and feeds on its living body, from within. The fly then emerges as an adult — by popping the ant's head off.

We’ll be safe in the cellar

Assassin bugs strum spider webs, mimicking a trapped and weak prey species. The spider thinks an easy meal has just landed. Nope. Instead, death has arrived.

Are you my mother?

Botfly maggots feed on the living flesh and guts of mammals. As an adult, the female botfly does not lay her eggs directly on prey. She’s too big and noisy. Instead, she captures a mosquito and lays her egg on it. “The mosquito then visits an unsuspecting human or other mammal, and the botfly's larva jumps onto the skin!” Kwapich said.

Yes, my pretties

In Central America, there is a parasitic worm that causes the gaster (abdomen) of one ant species to turn bright red, like a berry. This 'berry' is attractive to birds. They eat the ant, allowing the worm to complete its life cycle. When the bird poops, the parasite's eggs are spread around and collected by more ants.

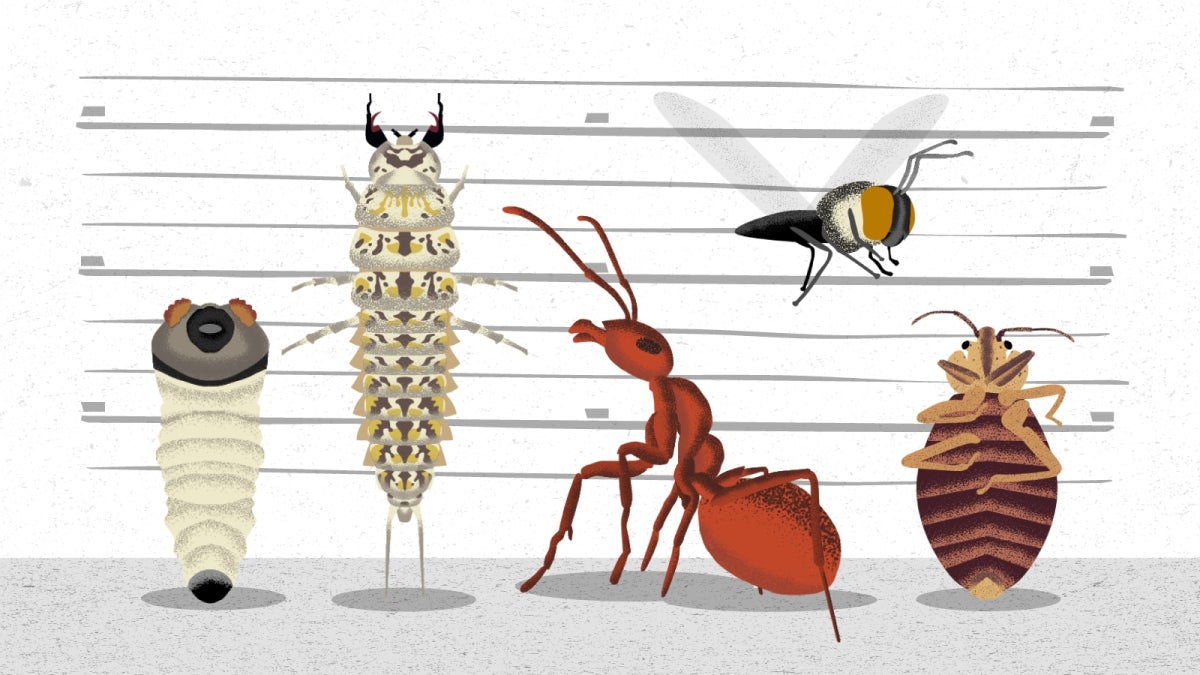

Top illustration by Alex Cabrera/ASU Now

MORE HALLOWEEN TREATS

- Unmasked: A Look at Halloween's costuming history

- ASU students tap into fantasy for 'Kiss of the Spider Woman' costumes

- The business of Halloween

- Pop-up stores: Getting into the 'spirit' of Halloween

- How to enjoy Halloween treats responsibly

- Monster mash-up: English profs' fave myths and legends

- Watch: 'Monstrum' host Emily Zarka talks monsters

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…