Editor's note: July 3 marks the start of "the dog days of summer," the most sweltering days of the year. (For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, anyway.) To help you make it through, ASU Now is talking to experts from around the university about everything dog, from stars to language to man's best friend. Look for new stories every week through Aug. 9. Woof!

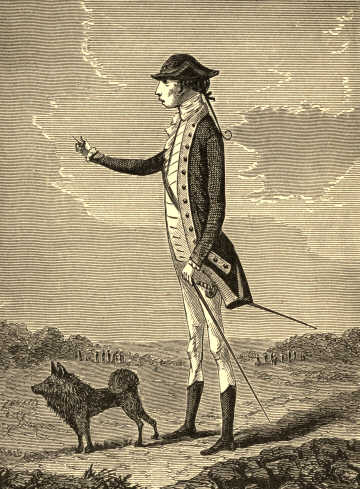

All who met Gen. Charles Lee during the American Revolution could agree on one thing: He was an absolutely miserable human being.

He swore a blue hurricane, wore dirty old clothes, couldn’t care less what people thought of him and admitted to being an unapologetic misanthrope. He insulted and needled George Washington so much that officers literally lined up to duel him.

But the man loved his dogs, and, as is the wont of dogs, they loved him back.

“To say the truth I think the strongest proof of a good heart is to love dogs and dislike mankind,” Lee once wrote. “I know very well that it is hazarding a great deal to profess a dislike to mankind in general, but if you are generous, undesigning and public-spirited yourself, you will naturally expect the same in others, and the frequent disappointments we meet with as naturally sours us against the whole species. … Now I (choose) to construe a cynical disposition a love of dogs, in preference to some other animals who are pleas’d to think their convenience, pleasures and dignity were the only objects of the great Creator of all things.”

When he was captured by the British, Lee wrote to Washington asking for his dogs: “... as I never stood in greater need of their company than at present.”

He isn't alone. History is filled with tales of otherwise difficult or horrid humans who express a deep love for their dogs.

“Dogs have the ability to love the most improbable people and to evoke in people who have difficulty loving other people … an affectionate response,” said Clive Wynne, founding director of the Canine Science Collaboratory at Arizona State University.

In these dog days of summer, whether you’re splashing about in the pool or relaxing with TV in the AC, your pup is at your side, happy to do whatever you want to do. Wynne is the author of "Dog Is Love: Why and How Your Dog Loves You." ASU Now talked to Wynne about the nature of that relationship and if it is love that makes dogs, in fact, dogs.

Question: What do we get from dogs that we don’t get from other animals?

Answer: What dogs bring is this unbounded capacity to love us, to experience and express strong emotional connections towards people. I don’t want to get in a fight with the cat people — there are affectionate cats. I’ve hung out with hand-reared wolves and foxes. You can, if you’re very careful, form emotional bonds with any number of different animals. But where dogs really stand out is it’s so easy to form affectionate relationships with dogs. They are really ready to do that. That is, I think, their most striking characteristic.

Q: The word you used in there really struck me: They express it. Another animal might feel it, but you’re just not seeing it the way you do with a dog.

A: That’s true. Dogs are highly emotionally expressive. … It’s really quite amazing to me how easy it is to get that sense from a dog that the dog is interested in you and cares about you. Some of that is behaviors that we humans have too, but it’s quite remarkable to me how we understand behaviors that we don’t share with dogs.

What I mean is a dog’s tail. Everyone who knows dogs knows what a dog’s tail means. Nobody has to educate you when the tail is up high and wagging then the dog is happy and when the tail is tucked tightly between the legs, the dog is anxious, sad, unhappy. We read that and we just experience it. You don’t intellectually think it over — "Oh, yeah, the tail is up; what does that mean now?" — you just experience it, and yet we don’t have tails. And we don’t take the limbs we have and use them in the same way, although I sometimes make a fool of myself when I’m giving talks and I raise my arm like a dog’s tail and I wag my arm. That’s really stupid, because nobody would do that. We don’t express our emotions in anything like that kind of way, and yet when we see our dogs do it we read it totally naturally, which I think is very interesting.

Q: Do you think that’s why they became the first domesticated pets, because they were reacting to humans like no other animal?

A: I think that’s a key part of their success, but if we’re talking about the history, the origin of dogs, then my guess is that this emotionality — and this is just a guess — isn’t where dogs started. I strongly suspect that for the first few thousand years dogs were around us, they weren’t anything like as emotionally expressive as they became. I think the emotional expressiveness probably came a little later. But it’s certainly been around for many thousands of years.

The evidence for people caring about dogs goes back 8,000 years when people buried dogs with great care. They didn’t just dig a pit and throw the body in. They were clearly making a statement with this burial. The dog they were burying was a highly valued individual. That’s something that starts to occur all across the world’s surface, places that are thousands and thousands of miles apart. Then, as long as 4,000 years ago in ancient Egypt, you can find one tomb inscription that identifies that someone took great care in burying that dog and they actually write out how much they cared about that animal. … Written language doesn’t go back that much further. It’s pretty much fair to say that as soon as people had the ability to write down their thoughts, some of the first thoughts we find that have survived from that long ago are thoughts about how much somebody cared about their dog. I find that totally amazing.

MORE DOG DAYS: Let's get Sirius — how star alignment has meant to humans and their language

Top photo: A black Pomeranian, an example of Gen. Charles Lee's favorite breed. Photo by Getty Images/iStockphoto

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…