It’s March 20, 1911. Former President Theodore Roosevelt is in town for the dedication of a dam 60 miles northeast of the Salt River Valley. His visit to Tempe is only intended to be two or three minutes long. He’s expected to speak standing from his car.

When he arrives at the campus of Tempe Normal School — now Arizona State University — he is greeted by hundreds. A huge flag hangs from the balcony of Old Main. Roosevelt bounds up the steps (he rarely does anything slowly) and speaks for 13 minutes in his patrician New York accent.

He speaks about the importance of an educated citizenry and the “far-sighted wisdom” of the Territory of Arizona. The dam is a sign that Arizona has left its wild past of gunfights and massacres behind. The territory is finally ready to earn its star on the flag and become a state.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt delivers an address from the steps of Old Main in March 1911. Photo courtesy of ASU Archives

“It is a rare pleasure to be here, and I wish to congratulate the Territory of Arizona upon the far-sighted wisdom and generosity which was shown in building the institution,” Roosevelt said. “It is a pleasure to see such buildings, and it is an omen of good augury for the future of the state to realize that a premium is being put upon the best type of educational work. Moreover, I have a special feeling for this institution, for seven of the men of my regiment came from it.”

***

That regiment was the famous Rough Riders of the Spanish-American War. The group was an all-volunteer cavalry regiment of cowboys, Native Americans, college athletes, East Coast blue bloods, ranchers, sheriffs, miners and policemen who banded together in 1898 to drive the Spanish out of Cuba. The regiment lasted for exactly four months and 13 days, and the last member died in 1975, yet they gained immortality with their legendary charge up San Juan Hill.

That charge, which happened 121 years ago July 1, propelled the Rough Riders into American myth. And when it was over, the hundreds of Arizonans in their ranks came home, rolled up their sleeves and went to work.

They became Arizona's governors, postmasters general, adjutants general, clerks of the Supreme Court, state historians and legislators, deputy game wardens, superintendents of schools — just about any government position in existence. They put the final touches on a territory that had long yearned for respectability, transforming it from unruly child to honorable brother.

The seven men who returned to Tempe Normal School were no different. This is their story.

***

Cubans had been revolting against Spain for some time. The U.S. was reluctant to enter the war because the country had just come out of a depression. President William McKinley wanted to stay out of it. But when the American battleship USS Maine mysteriously exploded in Havana’s harbor, the yellow press, led by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, inflamed populists with the cry “Remember the Maine!” (It was much later discovered that the ship's powder magazines likely blew it up, not a Spanish mine.) Congress issued a joint resolution, McKinley signed it, and the country was in its first war intervening with a foreign power.

The Spanish had a standing army of about 200,000 (not all in Cuba). The U.S. had a standing army of about 20,000.

“It was like, ‘Oh my God, we need volunteers yesterday,’” said reenactor David Williamson, president of the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, A Troop, Arizona Rough Riders Historical Association, based in Prescott. Williamson’s group gives talks to schools and marches in parades on holidays.

Roosevelt knew exactly where to look for the perfect volunteers. In the mid-1880s he had had a ranch in North Dakota. He learned to hunt, rope and ride Western style, eventually earning the respect of local cowboys. The West consumed Roosevelt, and around lawmen who had been in gunfights and the like, he was like a kid. He couldn't get enough of their stories.

“Roosevelt was like, ‘We’ve got the perfect guys already,’” Williamson said. “‘They don’t need to be trained. They’re the cowboys from out West. They already know how to ride a horse. … They certainly know how to shoot a gun. They’re used to eating lousy food and having lousy life conditions because they’re used to being out on the range.’ It was a perfect fit.”

Capt. Leonard Wood, who had been awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Apache Wars and who had been appointed temporary medical officer of the Department of Arizona in 1887, was chosen as commander. Roosevelt resigned his position as assistant secretary of the Navy, and with no military experience at all he was appointed lieutenant colonel.

Four areas were selected for recruiting: the territories of Arizona and New Mexico, Texas and the Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory (now one state). Thousands turned out to enlist.

"They volunteered in droves," Williamson said. “‘Being a soldier, well, I’m already kind of doing that.’ It was nothing new for them.”

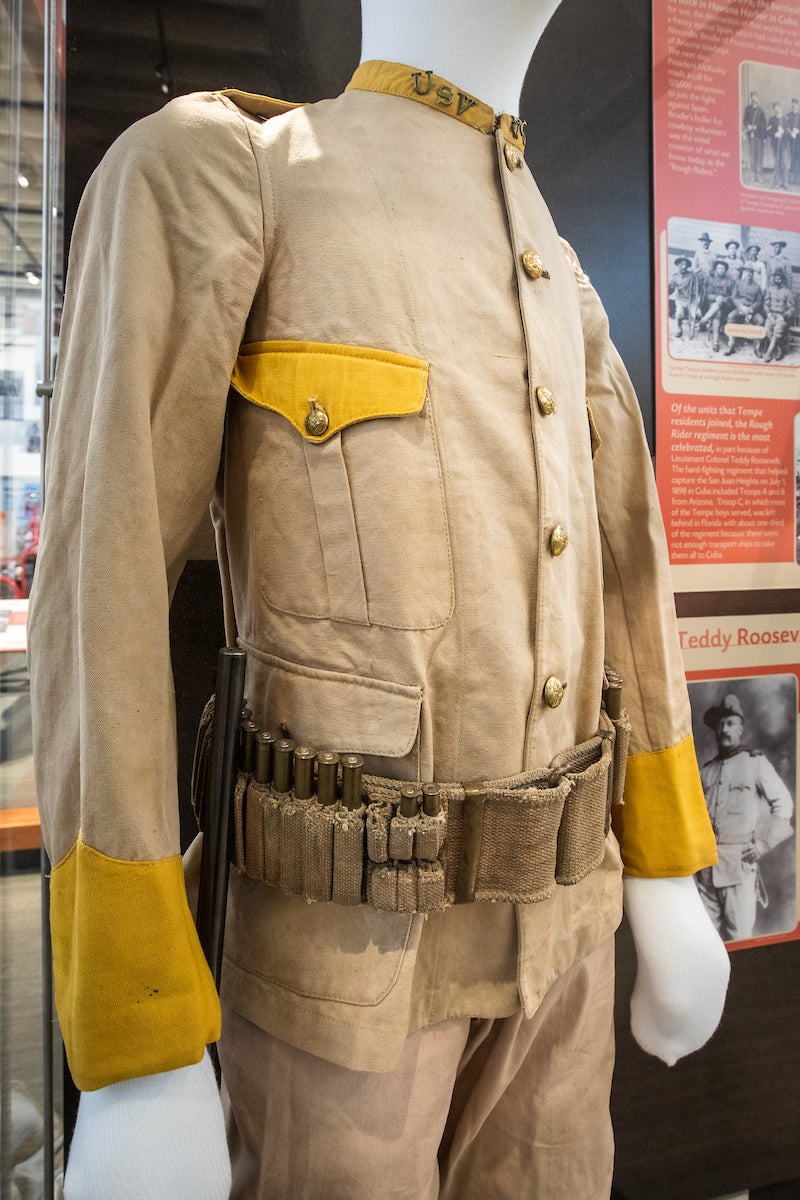

A typical canvas uniform of the members of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment is on display at the Tempe History Museum. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Thirty years after the war, Arizona Rough Rider James McClintock admitted that none of the Arizonans gave much of a damn about Cuba or Spain. They were in it for the adventure. A lot of the volunteers hadn’t been out of their towns, much less out of their state.

Roosevelt also put out the word among his peers in New York and New England. Harvard boxers, members of the Meadowbrook Polo Club and young men who knew steeple chasing and duck hunting with addresses at Fifth Avenue, Southampton and the Knickerbocker Club signed up.

Out West, there was criticism that the “cowboy regiment” was more hat than cattle. “The members of this so-called ‘cowboy’ regiment seem to have been recruited from the sort of cowboys that ranges up and down Washington Street, Phoenix,” an Arizona paper opined. “Many of them are not horsemen in the mildest construction, and as crack marksmen have yet to distinguish themselves.”

That was a criticism that could have been leveled at several of the Normal School’s Rough Riders.

Crantz Cartledge, J. Oscar Mullen, James C. Goodwin, J. Wesley Hill and John “Jack” A.W. Stelzreide all came from comfortable families. Cartledge and Stelzreide were avid tennis players and often won doubles matches together. The two best friends and Mullen all played football.

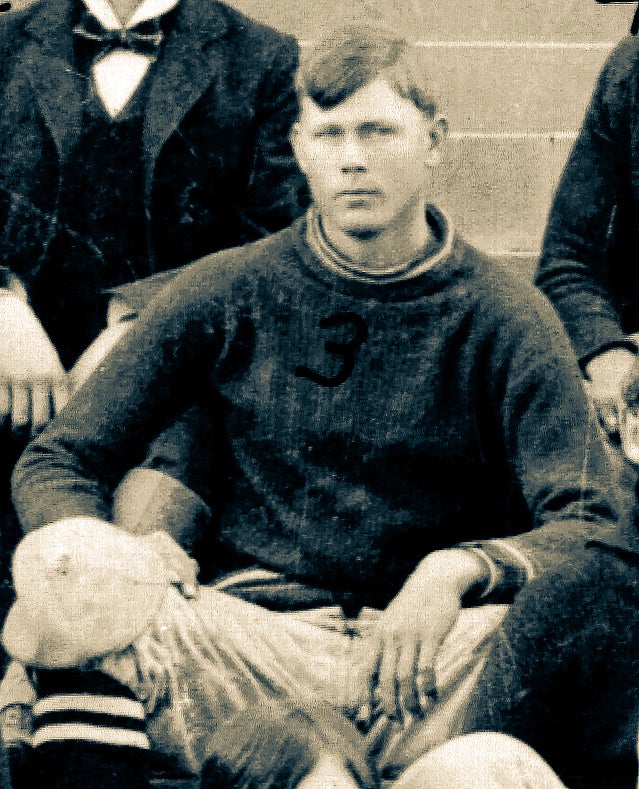

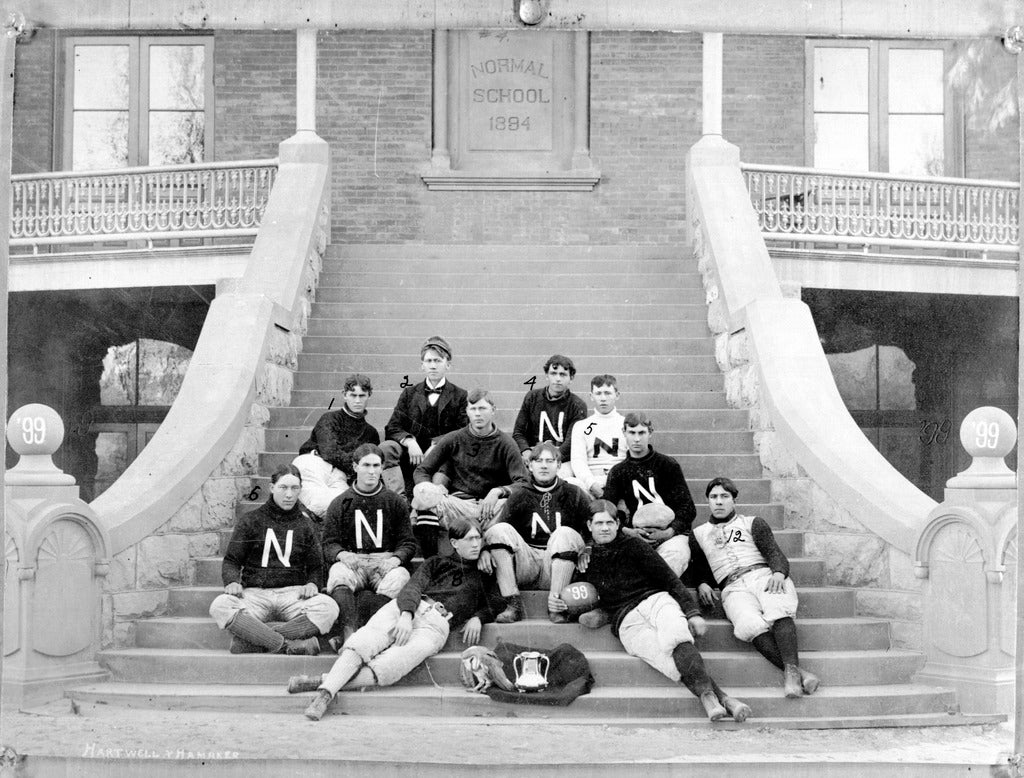

Jack Stelzreide, a member of the 1899 Territorial Cup-winning Tempe Normal School football team, was a member of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment (Troop C of Col. Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders). Photo courtesy of the ASU Library

Cartledge and Mullen played the first two known years of football at the Normal School in Tempe. Cartledge started at tackle on the school’s first officially recorded season in 1897 and played for two athletic seasons. Mullen played center as a senior on the school’s first football team in 1896. Stelzreide helped win the Arizona Territorial Football League Championship Cup in 1899 after the Normal team defeated the University of Arizona and went on to win the league championship.

The Arizona contingent weren’t any rougher — or posher — than any of their comrades, said Western historian Mark Lee Gardner, author of "Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill."

“I think they were very similar,” Gardner said. “It was a broad slice of society. There was criticism that the units weren’t actual cowboys/Westerners/frontier types. They were very similar to the guys from New Mexico and Oklahoma and the Indian Territory in that you had teachers, students, athletes — it really was a broad makeup of individuals and varying backgrounds. There were a few real cowboys.”

While being good horsemen and marksmen was important, the cri de coeur also sought “men of fine upstanding and moral character,” Gardner said. “That was just as important to make up the Rough Riders.”

In the end, whether they had never washed a shirt in their life or never owned two shirts at once didn’t matter.

“What’s to their credit is how these men of varying backgrounds came together so well,” Gardner said. “They became the clichéd band of brothers, not that they didn’t have their issues with one another at times. When it came time to support each other, they fought side by side very well.”

Another motivation — and a big one for the Arizona troopers — was statehood.

“They were all interested in doing whatever they could to promote Arizona,” Williamson said. “It wasn’t exactly the Wild West anymore, but it certainly wasn’t civilized. People were like, ‘Why would I want to go live in Arizona where it’s nothing but desert and jackrabbits? Those people out there are all crazy. It’s hot, it’s dry, there’s no water and the Indians are trying to kill everyone.' … Of course all the dime novels didn’t help.’”

William "Buckey" O’Neill was the most famous Rough Rider besides Roosevelt himself. He was a popular sheriff of Yavapai County known for capturing train robbers after a gunfight, an entrepreneur, attorney, newspaperman and later mayor of Prescott, among many other occupations.

“O’Neill’s big thing was, ‘Who wouldn’t give his life for a star?’” Williamson said. “He was talking about a star on the flag, because obviously Arizona was still a territory.”

One of O’Neill’s best friends was James H. McClintock. McClintock Drive, McClintock High School and McClintock Hall at ASU are all named in his honor. McClintock was one of the five graduates who made up the first class of the Normal in 1887.

When McClintock attended the Normal, the "library consisted of a dictionary, and the apparatus was a nice terrestrial globe — nothing more,” he said years later, according to various historical sources. “Drinking water was to be found in an olla (a large-mouthed pot) by the side of the front door. The water came from a well equipped with bucket and rope. Near it was the lavatory, comprising one tin basin.

"Almost everyone rode to and from school on horseback,” he said. “Many were the spirited races run on what is now known as Eighth Street, and occasionally one of the students would ride an unbroken colt to school that he might contribute to the gaiety of the day's session."

McClintock was 23 when he graduated. He bought an interest in and managed the Tempe News, acted as justice of the peace and deputy road overseer and ran his own 160-acre barley farm south of Tempe.

"In the early part of 1898 my old friend O'Neill dropped in on me with a great scheme for a cowboy regiment for the impending war with Spain,” McClintock wrote years later. “So a few weeks later I left Phoenix in April to what I believe was the first detachment for the Spanish War. Then came a lot of experiences!"

All the Normal men enlisted up in Prescott in the first few days of May. McClintock, who had experience working for the adjutant general at the Whipple Barracks during the last Geronimo campaign, was named captain of Troop B. The other six served in Troop C.

Thomas F. Grindell, 26, was an English teacher at the Normal. He resigned his position to join the Rough Riders. Just a week after he enlisted, he was promoted to sergeant.

Mullen (class of 1897) was a California native. Working as a rancher when the war broke out, the 21-year-old football player signed up on May 2. After four months, he was promoted to corporal.

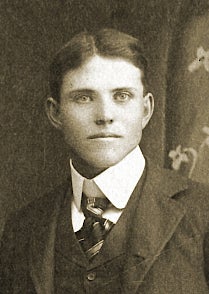

Undated photo of J. Oscar Mullen (1879–1954), who served with the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War. Photo courtesy of the Robert L. Mullen Collection in the ASU Archives of the ASU Library

Goodwin, from Missouri, had settled in Tempe and immediately become active in the community. Before the war, he built a free-service mule-drawn streetcar running from the river down Mill Avenue to Eighth Street (now University Drive), then east to the canal near Rural Road. He and McClintock were friends. McClintock convinced Goodwin to donate land south of Tempe for a schoolhouse, where McClintock began teaching. The pair convinced a number of Mexican families to move onto the land, then talked the local board of supervisors into creating a new school district. Their next move was to persuade the board to build roads around the school and name them road commissioners.

Goodwin and his half brothers designed and built Goodwin Stadium, now Sun Devil Stadium. He was one of the 15 donors who came up with the $500 to establish the Normal. Goodwin himself did not enroll until after the war, when he briefly studied mining.

Hill was 21 when he signed up. A California native, he had studied at normal schools in the Golden State. He completed his degree with a year at Tempe Normal, class of 1898.

Wesley Hill circa 1900. Photo courtesy of Annlia Hill

Cartledge, class of 1899, was the son of a wealthy farmer and something of a man about campus. A half-inch shy of 6 feet tall, he played football and was in the debate society (in November 1899 he argued against the proposition “Resolved, that the expulsion of the Chinese is just” in a Friday evening program). The class president was so popular the class presented him with a gold ring before he shipped out with the others to train in Texas.

Cartledge’s best friend was Stelzreide, whose father was a section foreman for the Maricopa and Phoenix Railroad who later became a Tempe city councilman. They lived at Sixth Street and Ash Avenue. Stelzreide played in a string band at the Normal and gave readings for the literary society. He also debated in the Hesperian Society with his buddy Cartledge and played baseball in a Tempe team.

On May 1, classes were called off. “It was too sad a time to study,” reported the Arizona Republican. “At 12:30 the school was called to order and addressed by Dr. McNaughton, who spoke briefly of the leaving for war of the teacher, T.F. Grindell, and the students, Crantz Cartledge, Oscar Mullen and Wesley Hill. Those who were to leave soon entered. The school sang patriotic songs, and tokens of remembrance were presented to the departing friends.”

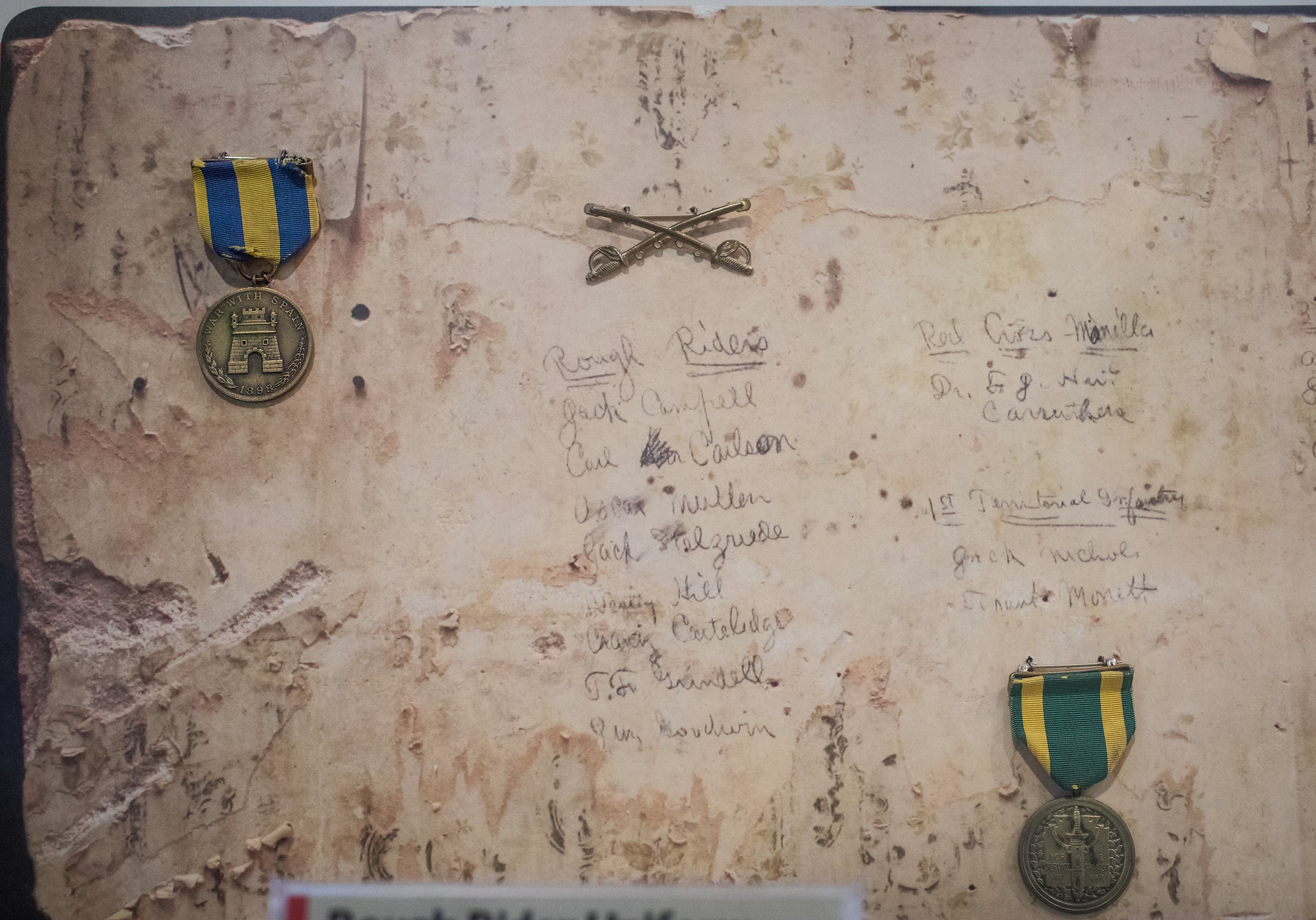

At some point, someone in Tempe wrote down the names of all the Troop C men on the wall of the Laird and Dines drugstore on Mill Avenue. (When the building was renovated in the mid-1990s, the section of wall was removed and preserved at the Tempe Historical Museum.)

A salvaged piece of wall on display at the Tempe History Museum includes the names of six of the seven members of the volunteer group of cavalry in the Spanish-American War who attended Tempe Normal School.

“The Phoenix volunteers are a fine-looking lot of young men and their captain, Jas. H. McClintock, looks every inch a soldier,” reported the Prescott Arizona Weekly Journal Miner on May 4.

The Arizona Rough Riders traveled by train to join the rest of the regiment in San Antonio for training. Training lasted all of about three weeks, most of it teaching the men how to ride as a disciplined cavalry instead of cowpunchers chasing a herd.

“It was wham, bam, thank you ma’am,” Williamson said. “How quickly can you get an army together and basically throw it at the enemy? It was absolutely insane. It’s amazing they pulled it off. … ‘I train for three weeks, and then I’m on a ship and a month and a half later I’m shooting Spanish in Cuba.’ Just think about how fast that happened. It’s mind-boggling. And they won.”

Not only is it mind-boggling, it’s unique in military history, according to Lt. Gen. Benjamin C. Freakley. A professor of practice of leadership for Arizona State University and a special adviser to ASU President Michael Crow for leadership initiatives, Freakley recently retired from the U.S. Army after more than 36 years of active military service, including leading troops in Afghanistan and the Middle East. He’s also a native of Prescott, the home of the Arizona Rough Riders.

The regiment’s short lifespan has no parallel, Freakley said.

“Not to the level in which they were rapidly organized, deployed to Cuba, employed and then came home and disbanded,” he said. “There are cases of militia more like in the Revolutionary War or Civil War where a local militia would be rapidly formed to try to do local protection of parts of our country, and then the militia would go back to what they were doing, but I think this is much more deliberate.”

1898 photo of members of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment (Troop C of Col. Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders). Top row right: Oscar Mullen. Top row eighth from right: Jack Stelzreide. Bottom row third from left: Wesley Hill. Photo courtesy of the Robert L. Mullen Collection in the ASU Archives of the ASU Library

It was extraordinarily swift, especially taking into consideration a lot of men from desert areas were being deployed to a jungle.

“The Rough Riders came together so rapidly, were basically trained — which would be a bit of a stretch — then deployed to Cuba and find themselves from the arid temperatures of Arizona to god-awful humidity in the jungle,” said Freakley, who has been to jungle school three times. “It was just a bit of a rapid rush to get this done. Thank goodness the enemy wasn’t a lot better than they were, or it’d be a different story.”

In San Antonio, people showed up in crowds to gawk at the men. The press couldn’t get enough of the cowboy regiment, dubbing them “Teddy’s Terrors” before the moniker “Rough Riders” overtook the rest. A popular song at the time — “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” — became their unofficial anthem.

In Texas, Hill was appointed corporal of Company C. Ten days later a sergeant left camp without a pass. Hill replaced him. He and Grindell were solicited by the regimental chaplain to form a choir. Stelzreide was appointed trumpeter. Mullen made corporal.

The troopers weren’t the only people learning. After one long, hot day of training, Roosevelt bought the men all the beer they wanted. In the officers’ mess that night, Wood brought up the subject of officers drinking with enlisted men, saying such an officer would be “quite unfit to hold a commission.” Roosevelt, embarrassed beyond measure, apologized.

On May 27, the regiment entrained for Tampa, Florida, the jumping-off point for Cuba and combat.

Tampa was a logistical disaster, a mess of men, horses and equipment arriving at odd hours and dumped in odd places. More bad news came from the Navy. There weren’t enough transports available to take the whole regiment or any of their mounts to Cuba. Wood had to make an ugly choice about which units would deploy to the island. Troop C was not selected. Of the Normal men, only McClintock would set foot in Cuba. And, without horses, the Rough Riders were now infantry.

Back in Tempe, commencement was held on June 16. It was an outdoor affair. Japanese lanterns were hung around campus and on buildings. “The rostrum was pretty as a picture,” reported the Arizona Republican. Sixteen people graduated. An empty chair decorated with an American flag sat on the stage in honor of Hill.

Most of the Normal men who remained behind in Florida got sick. Some of them were released from service. The rest remained in Tampa until they rejoined their comrades in August after Spain surrendered.

Hill resigned in Tampa, before the regiment embarked for Cuba. He submitted a handwritten note on July 20, “being physically unable to perform my duties in this capacity.” He had typhoid and yellow fever. He was granted furlough. He went to his parents’ home in California to recuperate, returning to Phoenix on Sept. 1.

Cartledge got sick during training in Texas, writing home that he had fever and measles for 20 days. Goodwin, sick, like the others, left the Rough Riders on Aug. 7, according to his military service record.

After a number of snafus, the Rough Riders sailed for Cuba. It took them seven days to steam around the east end of the island to a village named Daiquiri, 14 miles east of their target, the city of Santiago de Cuba, where the Spanish Atlantic battle squadron was holed up in the harbor. There weren’t enough provisions on board, and the men went hungry. The situation was not improved by a trooper who had bought an accordion in Tampa and was learning to play. It was thrown overboard when he wasn’t looking.

One June 23 the regiment began landing in small boats in heavy swells. Three Rough Riders trudged up a hill and planted the flag sewn by the Women’s Relief Corps of Phoenix on top of a Spanish blockhouse. “Yell, you Arizona men,” McClintock hollered. “That’s our flag!” The troops fired rifles and revolvers, ships' whistles blew and a band struck up “My Country 'Tis of Thee.”

The next day the landing continued. Reports came in that the Spanish were digging in. They were wrong; the Spanish general had ordered a retreat back through the jungle to Santiago. “Fighting Joe” decided to attack. It was a disaster. The Spanish halted their retreat and stood their ground. They fought with rifles that used smokeless powder, making them difficult to pinpoint in the dense jungle.

This was the Battle of Las Guasimas, the first of two actions fought by the Rough Riders, and the only battle a Normal man took part in.

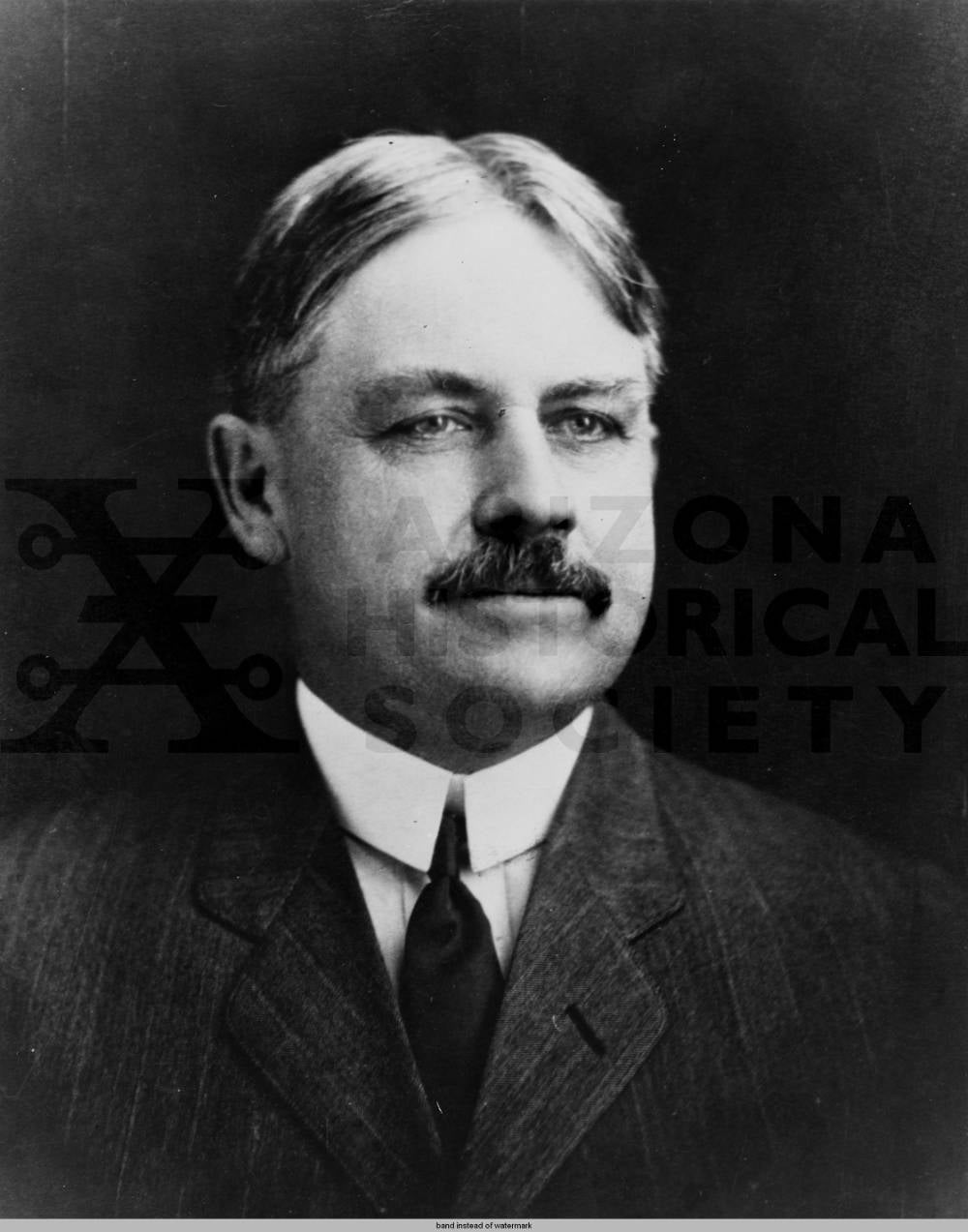

Captain James H. McClintock, B Troop Commander, 1st U.S. Voluntary Cavalry Regiment "Rough Riders" was injured at the Battle of Las Guasimas, Cuba, on June 24,1898, during the Spanish-American War.

McClintock was seriously wounded. A Spanish machine gunner shot him three times in the leg. He was escorted down to the beach, transferred aboard a ship and sent to recover at a hospital on Staten Island in New York. He was not released from the hospital until Thanksgiving. First Lt. George B. Wilcox, a Phoenix farmer, replaced him as Troop B commander. Later McClintock was given the brevet of major for gallantry in action. Details of his actions during the battle (and the entire Spanish-American War) were lost in a national archives fire in 1973.

Six days later the Battle of San Juan Hill took place. Actually, it was an assault upon two hills, the first named Kettle Hill. Both were taken in Civil War-style full frontal assaults by the Rough Riders and the 10th Cavalry, an African-American troop known as the Buffalo Soldiers. It was on Kettle Hill that Roosevelt was shot at by two Spaniards who jumped out of a trench. He fired back at both, killing one.

After Kettle Hill was secure, Roosevelt led the charge up San Juan Hill. He turned around to see only four or five men with him. Most of the others never heard his order or saw him take off. He returned, gave the order again, a bugle sounded, and Rough Riders, Buffalo Soldiers and other Army regulars swarmed up the hill. Bullets whip-cracked around them, artillery shells exploded and Roosevelt turned to his orderly. “Holy Godfrey, what fun!” he yelled.

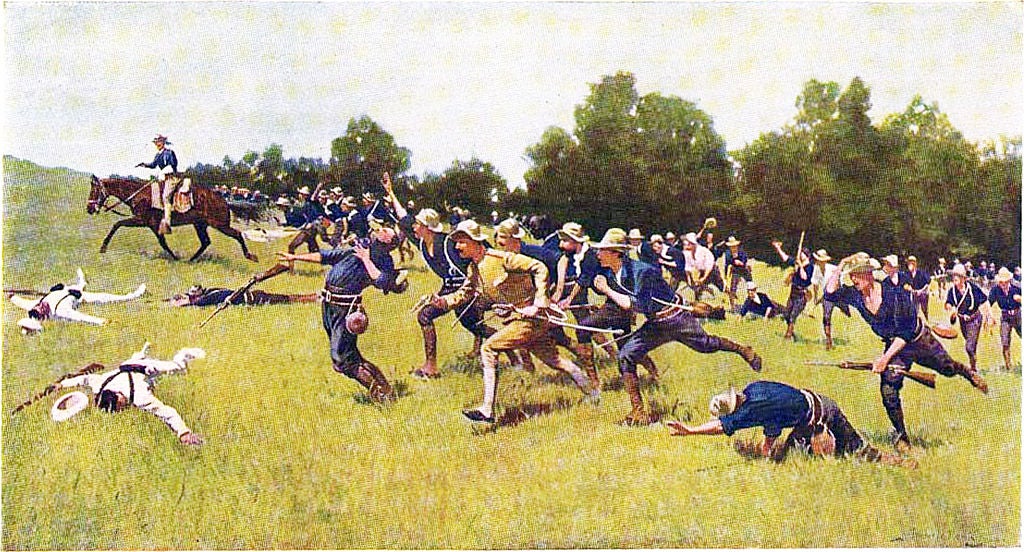

"The Rough Riders' Charge on Kettle Hill," by Frederic Remington.

Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2001. He is the only U.S. president to receive the medal, and one of the few presidents to kill a man in battle.

After San Juan Hill, the Cuban campaign was largely a naval affair. American invasion forces began to be pulled out on Aug. 7. Five days later Spain surrendered. The adventure was over.

One hundred and twenty-two Arizona men went to Cuba and fought in two engagements. Nine were killed and 20 wounded in the 10-week campaign.

The Rough Riders were carried by ship to Montauk Point on the eastern end of Long Island, New York, where they rejoined their comrades left behind in Florida, recovered from their tropical diseases and stayed in quarantine. Their history ended when they were mustered out on Sept. 15, four months and 13 days after they mustered up.

But Arizona’s fight was far from over.

***

Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders stand victorious atop San Juan Hill on July 1, 1898. The flag is on display in the museum in the Arizona State Capitol complex.

The Normal men trickled back to Arizona over a period of months.

On Sept. 31, Stelzreide and Mullen returned to Phoenix. Mullen was met in Phoenix by some of his brothers and driven to Tempe, surprising his parents and the community. Stelzreide stayed in Phoenix all night and came to Tempe the next morning. His parents didn’t expect him back so soon. Neither men were sick, and both returned home in “good health and flesh,” the Republican reported.

Hill returned in late September. He was offered a position at the Bonita school (a town that catered to soldiers and cowboys around Fort Grant; a ghost town since 1955). He turned it down because it was too far away. In late October he took over the school at Livingston. Livingston was a small farming and ranching town whose post office opened in 1896 and closed in 1907. It was located where the east end of Roosevelt Lake is now. It took Hill two days to ride from Mesa to Livingston.

Twelve days later, Stelzreide re-enrolled at the Normal. Toward the end of October, he, Grindell and another Rough Rider visited the school. Grindell made a few remarks, noting that even though he had only been away six months he didn’t recognize half the students. The school president introduced Stelzreide as “our John.” The following year Stelzreide suited up at fullback for Tempe Normal’s undefeated 1899 squad — the first to defeat rival Arizona.

Jack Stelzreide (third from the left, on the top row, with the number 3), a member of the 1899 Territorial Cup-winning Tempe Normal School football team, was a member of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment (Troop C of Col Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders). Photo courtesy of the ASU Library

In November, Cartledge, “the long looked for Rough Rider has returned and will enter the Normal next Monday,” the Republican reported. Later that month he and his buddy Stelzreide were feted at a dinner at a Mesa hotel, the Kimball House.

McClintock returned in December. He limped from his wounds for the rest of his life, carrying a cane made from a palo verde tree with an Arizona onyx handle.

He and the others who so readily flocked to Roosevelt’s banner would not be forgotten. In 1900, Roosevelt ran as William McKinley’s vice presidential candidate. McKinley won handily. Later the next year, he was assassinated by an anarchist. Roosevelt was sworn in as the nation’s 26th president.

“Those bonds that were forged on San Juan Hill were very, very solid and unbreakable,” historian Gardner said. “Once he became the most powerful man in the world, or at least in North America, he didn’t have to do what he did for these guys, but he did. His wife wrote that they were like his unruly children, that they were very proud of them, that they would help them if they could, and that they were always asking for something. There were several from the Arizona contingent that he formed a very favorable and close bond with, and it did influence Arizona politics.”

Roosevelt blatantly favored Rough Riders in any way he could after the war, whether it was appointing them to federal positions or bailing them out of jail. After the turn of the century, the governors of Arizona, Oklahoma and New Mexico were all former Rough Riders.

“Roosevelt was so thankful to the men who followed him,” Gardner said. “They adored Roosevelt. They supported him in his political endeavors. Some Rough Riders, while he was campaigning for governor, actually campaigned on the train. The bugler played at stops. They formed a bond that would last for the rest of their lives. Whatever political motivation might have been for gaining Arizona statehood, I think Roosevelt also felt he owed them careers or many favors. He tried to look out for his men. If his men wanted statehood, that certainly persuaded him to do what he could to make that happen.”

Pundits began to refer to the Rough Riders as a third party in politics. “It was that blatant and obvious,” Gardner said.

Gardner recounted an anecdote in his book where a congressman dropped by the Oval Office. A page informed him Roosevelt was in the office with a Rough Rider. “Then there’s no hope for me,” he said. “A mere congressman doesn’t stand a chance at all against a Rough Rider.”

Goodwin, for one, was disgusted by the favoritism. “I have the distinction of never holding an official position under the Roosevelt administration, and that puts me in a class by myself as far as this regiment is involved,” he said. “I’ve held no official position and never been in jail.”

(“It may have been a point of pride that he didn’t have to use his political connections to get where he got,” Gardner said. “Other men didn’t hesitate.”)

The one situation where Roosevelt drew a line was in the case of a Rough Rider who shot and killed his sister-in-law. He was not going to help a murderer.

The connection between Roosevelt and Arizona began in the war.

“It expanded in 1903 when Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon, when he was seated as United States president,” ASU University Archivist Rob Spindler said. “But in 1911, when Roosevelt came here two days after the opening of Roosevelt Dam, he knew the city of Tempe was posed for growth and the state of Arizona would soon become the 48th state. He said this community had advanced from being a frontier community to a modern community that had the economics and the government institutions that could become a state. … Within a year, President Taft would sign legislation that made the territory of Arizona into the state of Arizona. Teddy Roosevelt’s comments here on March 20, 1911, on the steps of Old Main were certainly a huge factor in that transition.”

In 1902, Roosevelt rewarded McClintock with the Phoenix postmastership, which he held for two nonconsecutive terms.

Col. James H. McClintock served as acting adjutant general for the territory of Arizona from Aug. 29, 1907, to Feb. 6, 1908. Photo courtesy of the Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records

The Spanish-American War did not complete McClintock’s military record. In June 1902, he was elected colonel of the First Arizona Infantry, where he commanded the regiment in a riot of 3,500 miners at Morenci. He handled the situation with firmness, protecting property and causing no bloodshed. For eight years he was at the head of the regiment and acted as adjutant general of Arizona through 1908.

McClintock listed himself as captain, colonel or major the rest of his life. He was 6 feet tall, weighed 218 pounds and had blue eyes and gray hair. McClintock was always neatly dressed, with his hair and mustache trimmed. He was courteous, but a secretary described him as having a “gruff manner, but most of the time his kind and generous ways prevailed.” He applied military discipline to the post office and his newspaper business. People called him Jamie or Colonel Jim. He called his wife, Dorothy, “dearikins” and “dearest-est.” It was said of McClintock, “he claimed to know everyone in the territory worth knowing.”

He was the first president of the Normal School Alumni Association and a member of the Board of Education. He wrote a three-volume history of Arizona and was appointed state historian. He served as president of the Rough Riders Association and was its historian. He was also the first commander of the Spanish War Veterans for the Department of Arizona. Poor health forced him to move to Los Angeles, where he died on May 10, 1934, at the age of 70.

***

Goodwin went on to be elected to the Arizona Territorial Legislature and served as chairman of the House committee on rentals of state school lands. He was again elected later and served two terms as a member of the Arizona House of Representatives in the second and third State Legislatures, 1915-1918.

Goodwin proposed and lobbied for the creation of the 2,000-acre Papago Saguaro National Monument, which was established by proclamation by President Woodrow Wilson. An amateur archeologist, Goodwin contributed numerous artifacts to the Smithsonian Institute and became a self-taught mining expert, serving as the longtime manager of the mineral exhibit at the Arizona State Fair. He constructed canals, railroads and highways, including the Kyrene Ditch and the Miami-Superior Highway. A member of the Tempe Old Settlers Association, he and his wife, Libbie, lived at 820 S. Farmer Ave. His house still stands and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Goodwin died in 1922 at 58. He is buried with other prominent Tempe residents in Double Butte Cemetery.

***

Following the war, Grindell briefly entered politics. He was narrowly defeated in a bid for school superintendent of Maricopa County, losing by 43 votes of 3,309 cast.

In 1905, he led a four-man expedition in search of rumored treasure on Tiburon Island off the west coast of Mexico in the Gulf of California. Nearly out of drinking water, the party became separated. Grindell and two others apparently perished, but their bodies weren’t found. More than a year later his remains were discovered by another group of explorers. Evidence at the scene seemed to confirm that dehydration was the cause of death.

Grindell was buried in Platteville, Wisconsin.

***

After the war, Mullen was chosen to be an Arizona Ranger by Gov. Alexander Brodie, another Rough Rider.

J. Oscar Mullen

Mullen became a Tempe Union High School trustee in 1909. A few years later, he was Florence's postmaster and school principal. He finished his career as superintendent of schools in Jerome and retired in 1949. He died in 1954, at age 75.

***

In 1900, Cartledge attended the University of Colorado at Boulder. Sometime later he got a lucrative job with the railroad in Alamogordo, New Mexico. He caught pneumonia and died in January 1902 at age 25. His “death … has cast a cloud of sorrow over the hearts of his many friends,” the Republican reported.

His father brought his remains back to Tempe, where he was buried on Jan. 7. Twenty-two carriages of mourners followed the hearse from the Baptist Church to Double Butte Cemetery. His pallbearers were all Rough Riders, among them McClintock, Goodwin and the staunch Stelzreide. A salute was fired over his grave, and a bugle sounded taps.

***

In 1900, Stelzreide was listed on the Yavapai County voter registration role as living in Crown Point. (Crown Point's history is intertwined with Brodie, the Rough Rider governor. The mines were started in the late 1890s complete with a mill and a town of about 100. Brodie left to enlist with Roosevelt's Rough Riders but funded the operation until 1905. Today Crown Point is a ghost town.) Stelzreide was probably teaching.

He left Arizona shortly thereafter, moving to Los Angeles, where he married his wife, Emma, and became a police officer. He rose to the rank of detective sergeant. Stelzreide lived in Santa Monica, California, with his family. He retired in 1938 and died not long afterward (in the 1940 census Emma is listed as head of household).

***

Teaching apparently did not agree with Hill. He briefly took a job as a letter carrier. When Brodie was made governor, Hill was appointed clerk of the board of control. In 1905 he worked as territorial auditor. He also worked in a Yuma bank and sold life insurance.

Cars, planes and anything that moved were Hill’s true passions. His tedious two-day rides over the Apache Trail to teach in Livingston inspired him when work began on Roosevelt Dam. He eventually owned a fleet of stage coaches that hauled workers out to the dam. In 1910 he managed the New State Auto Aerial Company, a Phoenix car dealership. That same year he was appointed secretary of the state Republican Party. (Motto: “Statehood First.”)

In 1911 during Roosevelt’s visit to the state and his now-namesake dam, Hill drove the lead car in the procession of 24 autos out to the dam. Hill family lore holds that when Roosevelt spotted him at the train station, he said, “I will ride with Wesley.”

The dam and the scenic Apache Trail leading to it became a major tourist attraction. Hill sold his stage coaches and bought 35 cars, which hauled tourists along the Apache Trail to Globe. He was highly successful.

In June 1917, he started the Apache Aerial Transportation Company, an early airline. It failed for lack of investors, but Hill managed to build the first airfield in Phoenix, at 16th and Jackson streets, not far from Sky Harbor International Airport today.

When America entered World War I, Hill tried to enlist in the air forces. He was rejected because of his age. The tank corps accepted him, however. He never went overseas. When the armistice was signed, he had served six months as a tank driver instructor.

After the war, Hill worked as state deputy game inspector for many years. He ran unsuccessfully for U.S. marshal in 1921 and secretary of state in 1922. His wife, Viola, whom he married in 1899, was socially prominent, hosting luncheons for the ladies of Phoenix.

In 1924, the Hills moved to Southern California. He managed the Hill Brothers Service Station in Long Beach.

Rough Rider reunion, Los Angeles, 1939. Wesley Hill is bottom row far right. Courtesy of Annlia Hill

Hill was an inveterate teller of tall tales. He claimed to have named the Apache Trail. (It was the Southern Pacific Railway Company that coined the name in its advertising campaigns to promote automobile side tours of the Theodore Roosevelt Dam and the Apache Trail.)

One of Hill’s brother’s grandsons remembered him years later.

“I remember that he was known for telling tall tales of his adventures through life,” Donald Raymond Hill said. “Some were true and some were not. I remember sitting on his knee at the gas station on Signal Hill, Long Beach, telling me these tales. I don't remember which story he told, but the common ones that circulate in the family are his Rough Rider experiences; the time he under-sheriffed to Wyatt Earp in San Diego, California; disarming a desperado on the Arizona-Mexico border who had holed up in a school or other civic building with hostages; attempting to start the first transcontinental airline — failed; starting a stage/bus line — true, standing for office, I think treasurer, in Arizona; having Pancho Villa in one of his classes — like his mother Mary Bradley Hill he taught school for a short time; and several other stories I can't recall at the moment. As the family said, as a mantra, 'Wesley was a real character.'"

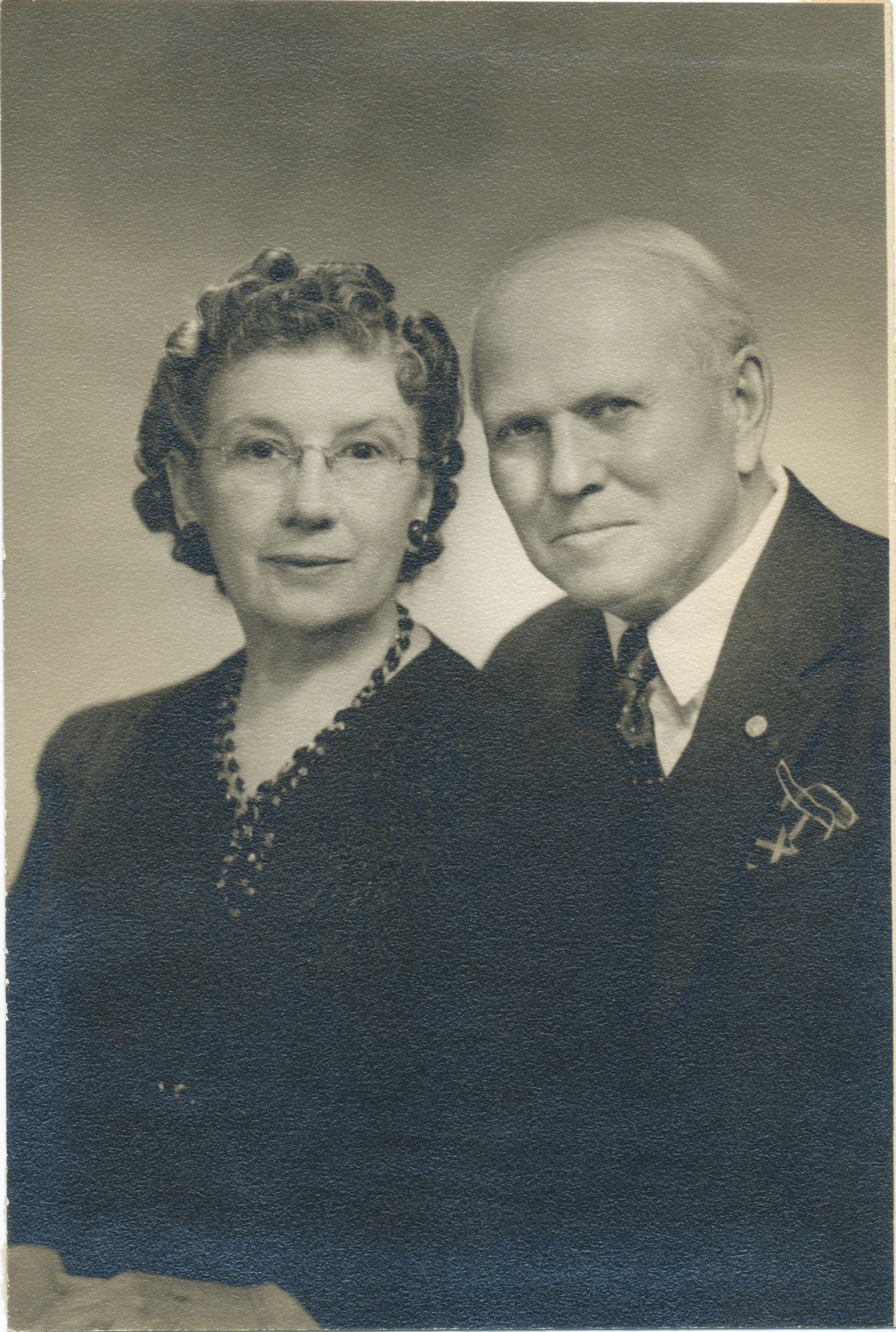

Viola and Wesley Hill. Courtesy of Annlia Hill

Hill died in April 1945.

***

The most famous Arizona Rough Rider, Buckey O’Neill, didn’t survive San Juan Hill. On the morning of the battle his troop was pinned down in a dry creekbed while Spanish snipers shot at them. Trying to rally the morale of his men, O’Neill walked up and down the line, calmly smoking a cigarette. When someone warned him to get down, O’Neill replied, “The Spanish bullet hasn’t been made which can kill me.”

Almost immediately afterward he was shot in the mouth and killed. The statue in front of the Yavapai County Courthouse in Prescott is not O’Neill.

“It’s a statue of the Rough Riders that kinda looks like Buckey O’Neill,” Williamson said. O’Neill was buried in Cuba. His remains were later exhumed and repatriated to Arlington National Cemetery.

Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery to the "Rough Riders," Arlington, Virginia. Photo by Carol Highsmith/Courtesy of the Library of Congress

“I’ve put my hand on his grave,” Williamson said. “Not a lot of people know about the Spanish-American War. … In high school the Spanish-American War is a couple of paragraphs, if that. There’s so much local history about these guys. … That’s what makes it interesting for me.”

On Feb. 14, 1912, President William Taft signed the bill granting Arizona statehood.

Top photo: The day prior to the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry's departure from Arizona to fight for Cuba's independence, the unit could find no American flag. The Women's Relief Corps of Phoenix sewed this flag, on display at the Arizona Capitol Museum, in one night. Called the "Rough Riders' Flag," it saw action throughout the Spanish-American War, including the Battle of San Juan Hill. Seven members of volunteer group of Col. Theodore Roosevelt’s cavalry in the conflict attended Tempe Normal School (later ASU) either before or after the 1898 war against Spain’s colonial policies with Cuba. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU workshop trains educators, professionals from marginalized communities in disaster science

As devastating as hurricanes can be to anyone caught in their paths, they strike marginalized communities even harder.To address this issue, a fund named for a former Arizona State University…

ASU’s Humanities Institute announces 2024 book award winner

Arizona State University’s Humanities Institute (HI) has announced “The Long Land War: The Global Struggle for Occupancy Rights” (Yale University Press, 2022) by Jo Guldi as the 2024…

Retired admiral who spent decades in public service pursuing a degree in social work at ASU

Editor’s note: This story is part of coverage of ASU’s annual Salute to Service.Cari Thomas wore the uniform of the U.S. Coast Guard for 36 years, protecting and saving lives, serving on ships and…