Women get autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, eight times more than men do. On the other hand, women have a smaller risk of getting nonreproductive cancers such as melanoma and colon, kidney and lung cancer.

And while there are some exciting developments in cancer treatments, such as immunotherapies, research is showing that women are responding more favorably than men to this type of intervention.

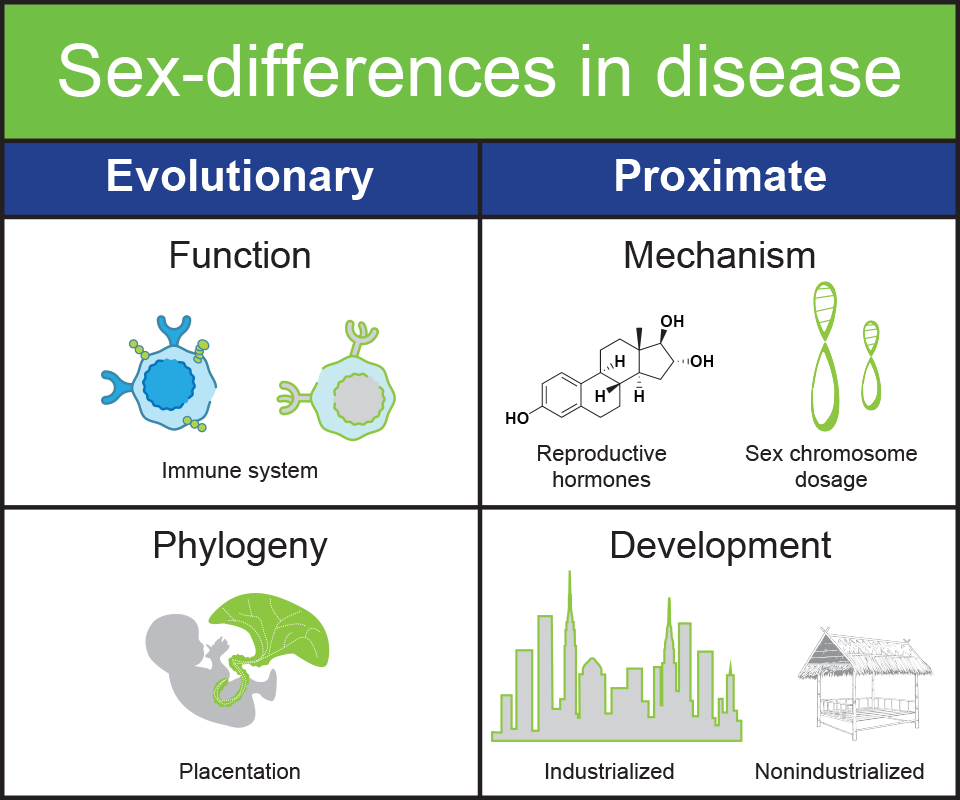

So why is there such a big difference between women and men when it comes to human diseases?

An interdisciplinary team of scientists at Arizona State University believes it may have the answer.

In a paper published Tuesday in the scientific journal “Trends in Genetics,” the team presents a new hypothesis to explain the phenomenon, setting the stage for novel research avenues focused specifically on treating autoimmune diseases and cancer.

“Until now, the differences between women and men in regards to human diseases have not been explained by existing theories,” said Melissa Wilson, assistant professor with ASU’s School of Life Sciences and senior author of the paper. “We are proposing a new theory called the Pregnancy Compensation Hypothesis.

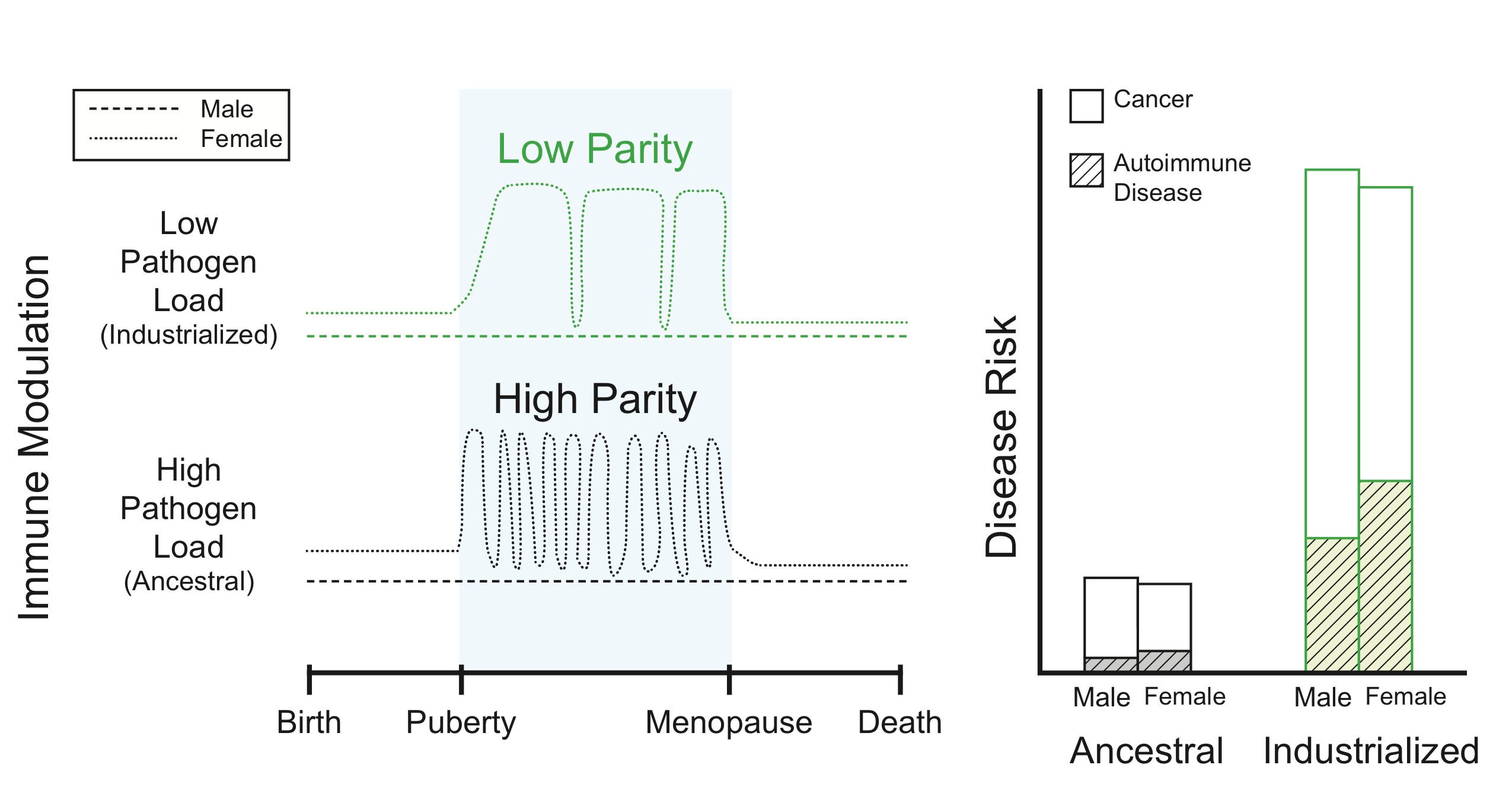

An illustration of the expected immune differences between high and low parity (layered on top of high/low pathogen load). The study suggests that low pathogen load (hygiene hypothesis) affects immune function in both men and women (green lines), making everyone more susceptible to autoimmune disease, whereas low parity will only affect the immune system in women, exacerbating the immune compensation that evolved in response to tolerating an internal pregnancy, further increasing the immune risk for women in industrialized regions.

“Basically, women’s immune systems evolved to facilitate their survival during the presence of an immunologically invasive placenta and pregnancy, and compensate so they could also survive the assault of parasites and pathogens. But now, in a modern, industrialized society, women are not pregnant all the time so they don’t have a placenta pushing back against the immune system. The changes in their reproductive ecology exacerbate the increased risk of autoimmune disease because immune surveillance is heightened. At the same time, we see a reduction in some diseases, like cancer,” Wilson said.

Heini Natri, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar with the ASU Center for Evolution and Medicine, said because the immune system varies between the sexes, it should be considered when developing immunotherapies and other treatments.

“We think the Pregnancy Compensation Hypothesis can explain why there’s a big sex difference in these diseases. Going forward, understanding the evolutionary origin of the sex bias in these diseases can help us better understand the mechanisms and particular pieces of the immune system we can target,” Natri said. “Our goal is to actually make treatments better for everyone. We are realizing that cancer is different in men and women. In the study of most cancers and other diseases, and so far in the development of cancer treatments, that has not really been taken into account.”

Effects of industrialization

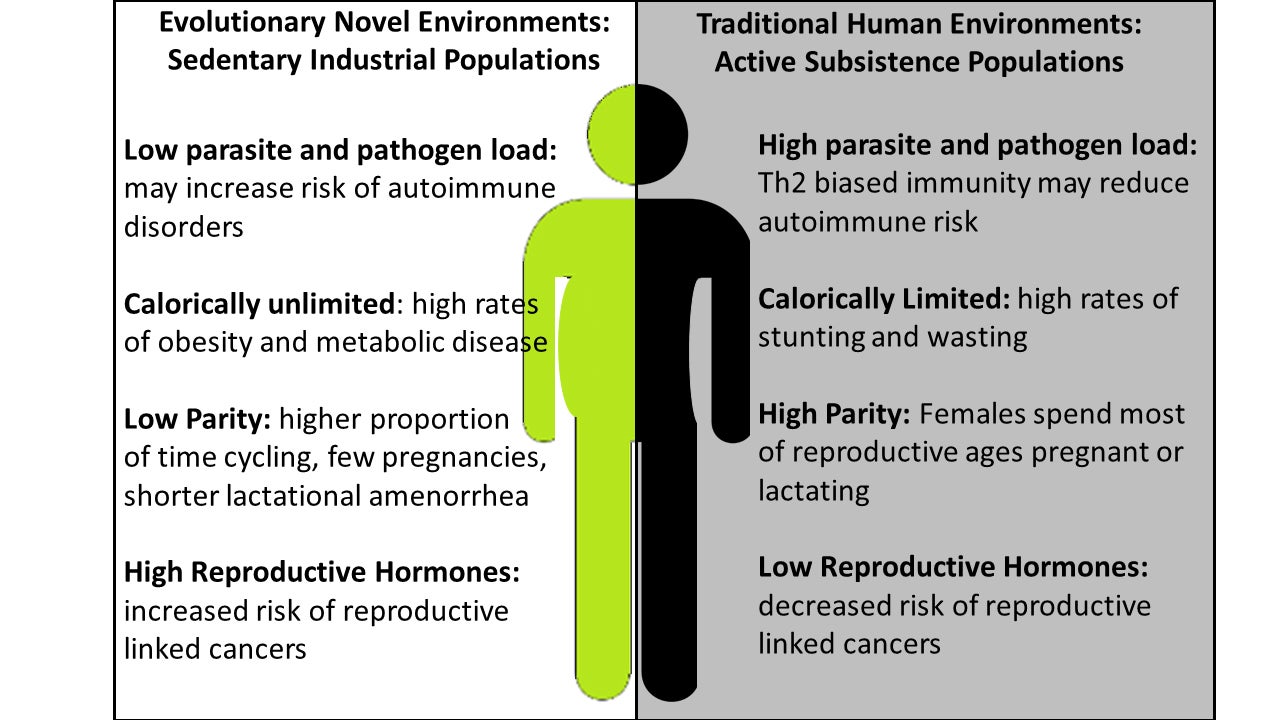

Another factor that may exacerbate this situation is living a modern-day, urban lifestyle.

In industrialized communities, autoimmune diseases appear to occur at a much higher rate than in nonindustrialized populations. The researchers believe the human immune system evolved expecting a given load of parasites. In the modern environment, exposure to those parasites has diminished so the immune system has fewer foreign targets. With this reduced load, the immune system attacks 'self' but also finds cancer.

“There is a mismatch between the ancestral environment humans were adapted to, and the industrialized environment many people currently live in. In terms of an evolutionary timescale, our environment has changed incredibly fast,” said Angela Garcia, also a postdoctoral research fellow with the center.

“We have also shifted from an active lifestyle to a sedentary one. We now have an overabundance of calories available, which potentially allows us to maintain excessive levels of hormones, including the female hormone estradiol. Maintaining such high levels of hormones may increase the chance of triggering autoimmune diseases,” she said.

Although evolution has shaped sex differences over millions of years, industrialized urban populations experience exacerbated sex differences in hormone mechanisms as well as reduced pregnancies compared with nonindustrialized populations.

Future treatments

The researchers suggest that by framing future research within the Pregnancy Compensation Hypothesis, scientists could dive deeper into the characterization of genes, environmental context and the longitudinal history of people.

“We think this is more than a hypothesis. By using modern molecular biologic techniques in genetics and genomics, we can look at the differences between male and female immune systems, and between modern immune profiles and those in pre-industrial populations. By doing so, we may find new ways to prevent cancer and autoimmune diseases,” said Ken Buetow, a professor with the school and co-author of the study.

The researchers also suggest there are places where genes are regulated uniquely in males and females, as well as across environmental contexts.

“Going forward, we need to systematically collect environmental variables like pathogenic exposure, levels of stress and reproductive hormones and parity. We have to understand these areas better,” Wilson said.

This study is an interdisciplinary, collaborative effort including researchers from the School of Life Sciences, Center for Evolution and Medicine, and the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. This study is supported by the following: ASU School of Life Sciences; ASU Center for Evolution and Medicine; Prevent Cancer Foundation; Marcia and Frank Carlucci Charitable Foundation; ASU Biodesign Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health #R35GM124827; National Institute on Aging #RF1AG054442-01.

Top illustration: Jacob Sahertian/ASU VisLab

More Science and technology

The Sun Devil who revolutionized kitty litter

If you have a cat, there’s a good chance you’re benefiting from the work of an Arizona State University alumna. In honor of Women's History Month, we're sharing her story.A pioneering chemist…

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…