“Eat healthier and exercise more.”

Millions of people around the world living with Type 2 diabetes or prediabetes hear this suggestion from their doctors. But Stavros Kavouras, director of the Hydration Science Lab at Arizona State University, thinks a key element is missing from this prescription — water.

“Water is the forgotten nutrient,” said Kavouras, a professor of nutrition in the College of Health Solutions. “People forget to drink water, forget to study water, they just forget to include water in anything. The MyPlate, the USDA’s current nutrition guide, does not even include water because every dietary guideline needs to be evidence-based and we have little evidence for water.”

According to Kavouras’ research, drinking more water could be a simple, effective and inexpensive way to improve the quality of life for patients with Type 2 diabetes and potentially help prevent the disease in others.

Water has surrounded Kavouras his entire life. He lapped through water as a former member of the Greek national swim team, encouraged others to drink water as an exercise physiologist and now researches the effects of hydration on chronic disease outcomes in the Arizona Biomedical Collaborative at ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus.

Drawn to ASU’s interdisciplinary and collaborative culture, Kavouras explains that diabetes care requires a strong, multifaceted, solution-oriented approach because of its relentless nature as a chronic disease.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think we are making a dent in diabetes,” Kavouras said. “When we look at fatalities, no one drops dead from diabetes. People die from complications related to diabetes. We forget diabetes is a big problem. It is a cause of a lot of the major health issues, costs and problems in our society.”

The water-blood sugar link

Kavouras’ research on hydration started to draw attention when he examined the effect of low water intake on blood vessel function. He found that low water intake has detrimental effects on arterial health, comparable to the damaging effects of smoking a cigarette.

The surprising results from this study made Kavouras thirsty for more.

He led a study in which he regulated water intake among people diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. The research team examined the subjects after consuming ample water, according to the dietary guidelines from the Institute of Medicine, and a second time after decreasing their water intake to small amounts.

They found that diabetic patients were able to regulate their glucose levels significantly better when they were properly hydrated.

To understand why this was happening, Kavouros went on to study the effects of hormones that control the conservation of water in the kidneys, known as antidiuretic hormones. These are activated during dehydration.

The researchers increased levels of these hormones in participants and studied how they responded to a glucose tolerance test. Participants had 10%-15% higher blood sugar levels when water conservation hormones were stimulated. This suggests that when the body conserves water because of improper hydration, its ability to process glucose is impaired.

Stavros Kavouras in the Hydration Science Lab at ASU. Photo by Andy DeLisle

A healthy start for kids

Kavouras’ continued interest in hydration flowed into his current investigation of hydration in children. He wants to know what causes kids to be better hydrated, looking at factors such as environment and parenting, socioeconomic status, ethnicity and cultural practices among schoolchildren and their parents.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), more than 60% of children do not meet dietary guidelines for water — even greater than the 50% of U.S. adults that are underhydrated. Additionally, 3 out of 4 kids consume more than one sugary drink a day, and 1 in 4 kids do not drink water at all.

“These data are discouraging and saddening at the same time,” Kavouras said. “If we see that a significant portion of the population does not meet the guidelines, we know that these people are chronically elevating their antidiuretic hormones. This elevation is the mechanism we believe could lead to the development of diabetes later in life.”

Kavouras recounts times that his friends and educated colleagues would admit they didn’t remember the last time they had a sip of water or said they didn’t like water’s lack of taste.

“It’s understandable why this happens,” Kavouras said. “If someone grows up only drinking sweet flavors and you finally drink something without any flavor then it will be weird. We are exposed to sweetness as a planet and in the U.S. we are overexposed to this sweetness.”

Despite the discouraging statistics in children, Kavouras explains that there is a lot that parents and educators can do.

“Giving access to water is the best thing we can do for our children,” Kavouras said. “If you only have healthy options then you have a higher opportunity of consuming healthier options. Especially at an age where kids do not drive cars or cook their own food, we are the ones responsible at that time of life for the habits kids develop. Let’s establish healthy habits instead of unhealthy ones.”

When he moved to Arizona, Kavouras was happily surprised by the emphasis on hydration in the Valley and at ASU specifically. He received ASU water bottles at each welcome event he attended and now boasts an overflowing collection of Sun Devil hydration gear.

“This is a good trend in such a hot state,” Kavouras said. “Let’s use the fashion and trends of collecting and carrying water bottles to promote healthy habits everywhere.”

He explains that with the dry climate in Arizona, it is especially important for people to stay hydrated to avoid dehydration and prevent long-term consequences associated with low water intake.

How much water should you drink?

However, Kavouras waves caution toward adhering to the “8x8 rule,” a theory stating adults should drink eight glasses of eight ounces of water daily to stay properly hydrated. The rule may be a good minimum for water intake, but there is no data to support the guideline.

In 2004, the Institute of Medicine published water intake guidelines for Americans for the first time. The guidelines were based on data from the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The institute based its recommendations on the median water intake reported by Americans.

Though the publishing of hydration guidelines was a breakthrough in the hydration science community, Kavouras explains that what people are currently drinking doesn’t dictate what people should drink. The self-reported data used to create the NHANES water intake guidelines are insufficient and expose flaws in research standards for hydration in the United States.

Kavouras says that there are better indicators of hydration built right into our bodies.

“I monitor how many times I go to the bathroom,” he explained. “If it has been several hours and you haven’t been to the bathroom, this is an indication that you haven’t been drinking enough water.”

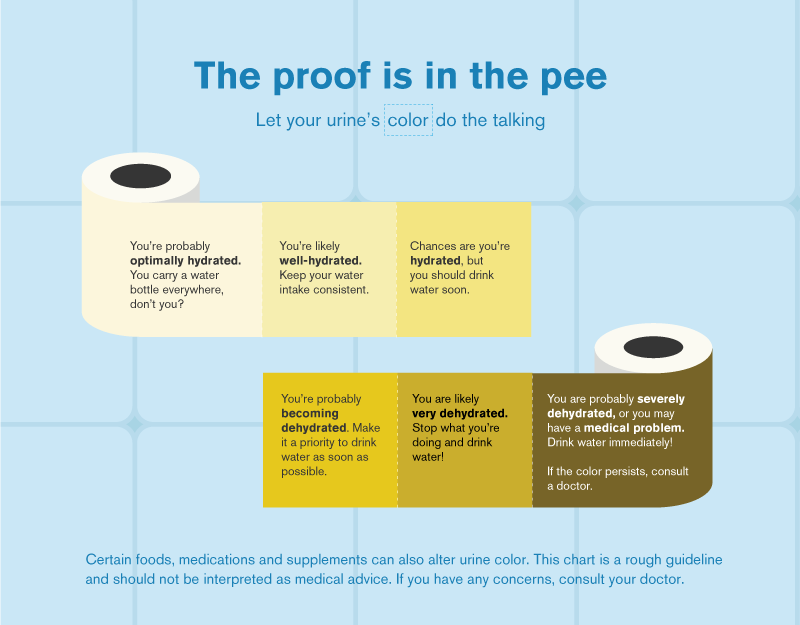

Another tip Kavouras offers is to look at the color of your urine. Dark yellow urine is more concentrated, indicating that the body is trying to conserve water because it isn’t getting enough. It also means that antidiuretic hormone levels are increased, which Kavouras linked to higher blood sugar levels.

The fix for concentrated and infrequent urine?

“Just drink more water,” Kavouras said.

Illustration by Charity Chong

Kavouras suggests his own personal habit of keeping a full glass of water in front of him at all times of the day.

“If you asked me how much water I drink in a day, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I don’t count how much water I drink,” Kavouras said. “Instead, I always have access to water in front of me. If we don’t have it right in front of us we won’t drink it and will only remember when we get very thirsty and drop everything in search for water.”

According to Kavouras, hydration science is growing rapidly, as interests and ideas continue to flood the field. He and his team intend to conduct more research on the exact mechanisms behind excess glucose during dehydration.

“There are two potential possibilities,” Kavouras said. “Either your liver is producing more glucose or your muscles cannot uptake the extra glucose. Or a little bit of both.”

“There are a lot of ideas in the future but we need to establish the direct link whether the effects of water intake are acute or long-term,” he added. “We are barely scratching the surface of the topic.”

As heat strikes the Valley in the coming months, Kavouras encourages us to remember that drinking water doesn’t only quench our temporary thirst; proper hydration is a key habit that benefits our bodies and determines our health far into the future.

Written by Maya Shrikant.

Top photo courtesy pexels.com. Editor's note: An earlier version of this story did not differentiate between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. The findings discussed here pertain to Type 2.

More Science and technology

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking risks, having a hard time resisting temptation, difficulty getting…

Will this antibiotic work? ASU scientists develop rapid bacterial tests

Bacteria multiply at an astonishing rate, sometimes doubling in number in under four minutes. Imagine a doctor faced with a patient showing severe signs of infection. As they sift through test…