He was a civil rights activist and academic.

The son of a Native American who taught at an all-black college.

A bold demonstrator in the bloody 1963 Woolworth's lunch counter sit-in that focused intense national debate on segregation.

A personal friend and associate of NAACP head Medgar Evers, who was assassinated at his Mississippi home by a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

John Randall Salter Jr., who received two degrees from Arizona State University in the 1950s and 1960s, died Jan. 7 at his home in Pocatello, Idaho, of natural causes. He was 84.

“Beyond alumni, beyond student and teacher, beyond any label we might have, we are all humans,” said ASU President Michael M. Crow. “And to stand up for your fellow humans, to take the hard path and challenge the status quo, to say, ‘This is wrong’ and then do something about it — this is an example of greatness. The ASU community has lost a true changemaker in John R. Salter.”

Social justice warrior

Though a lifelong social justice activist, Salter’s defining moment occurred in his late 20s when he answered the call by NAACP State Field Secretary Medgar Evers to join several students from Mississippi’s historically black Tougaloo College at a segregated lunch counter inside the F.W. Woolworth’s retail store on Capitol Street in downtown Jackson. The May 28, 1963, controversy erupted in chaos and violence when activists ordered service.

The peaceful protesters were taunted and brutalized by a hostile mob, who doused them with sugar, mustard and ketchup. Many of the women were pulled off their stools by their hair while the men were brutally beaten — some knocked unconscious and taken to the hospital. Salter later recalled in interviews that he had been attacked with brass knuckles and broken glass. He also had cigarettes stubbed out on his back and neck, leaving permanent scars.

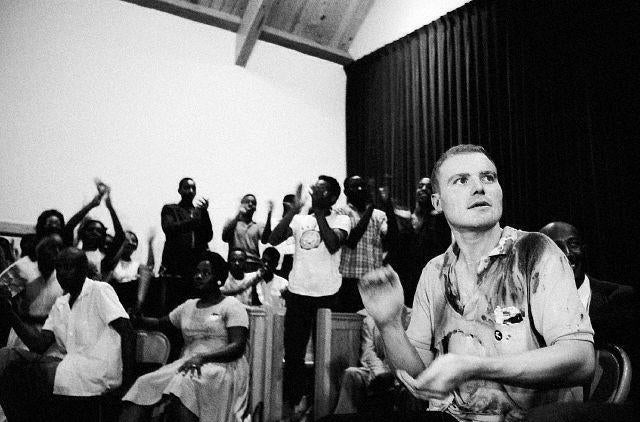

John Richard Salter Jr. at a Blair Street A.M.E. Church in Jackson, Mississippi, where he spoke to the congregation in his torn and bloody shirt in the early 1960s. Photo courtesy of HunterBear.org

"We learned later that local radio stations were encouraging people to go there and participate in mob activity," Salter recalled in a 2015 article for The Guardian, a British daily newspaper. "All the while the air was filled with obscenities, the N-word — it was a lavish display of unbridled hatred."

The taunting and torment went on for three hours before police grudgingly ended the protest, mostly to prevent damage to the store when the mob began throwing merchandise.

A photo taken by Fred Blackwell of the Jackson Daily News forever preserved the moment in history and was later used in various teaching textbooks.

In Jackson, Salter earned the nickname "Mustard Man" because the photo showed him drenched in condiments.

The Woolworth's demonstration made worldwide headlines, and two weeks later President John F. Kennedy used the flashpoint as a rallying call for a comprehensive national civil rights bill. That same night, Evers was struck in the back of the head by a bullet fired by an assassin’s rifle.

It was Salter who appealed through a telephone call to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. to come to Jackson for Evers’ funeral. King immediately agreed and ended up leading a procession of 5,000 people.

Salter published a book in 1979 about his civil rights experiences called “Jackson, Mississippi: An American Chronicle of Struggle and Schism.” The book was revised and updated in 2011 by Bison Books/University of Nebraska Press.

Unsung hero of the civil rights movement

ASU's Neal A. Lester called Salter an unsung hero and an inspiring figure.

“Mr. Salter’s story is a reminder that unsung heroes for justice are always among us. To put a face and story with the iconic Woolworth’s sit-in photograph, especially someone with an Arizona connection, is refreshing,” said Lester, professor of English and director of Project Humanities. “Too often our American history relegates such icons and iconic moments to the Deep South. That Mr. Salter was an educator who joined his students in protest is inspiring. He modeled the risk-taking that is so fundamental to demonstrating our own humanity and each other’s.”

Born on Feb. 14, 1934, in Chicago, Salter was raised in Flagstaff, Arizona, where his American IndianSalter said his father was a Wabanaki Indian. father was an artist and college professor. His mother was also a teacher.

Salter graduated high school in 1951 and served a stint in the Army. He pursued his undergraduate degree in social studies from Arizona State University and graduated in 1958 — the same year the institution was officially recognized as a state university. Two years later he received a master’s degree in sociology. While at ASU, he organized student groups and did volunteer work for the International Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, among other groups.

He continued his work as a labor union organizer before moving to Jackson, Mississippi, in 1961 with his wife, Eldri Johanson. Salter was an assistant professor at Tougaloo College and also served as an adviser to the Jackson Youth Council of the NAACP and as an executive committee of the Jackson NAACP, working closely with Evers.

Salter quickly became a civil rights leader and community organizer. He and his wife helped organize boycotts of several businesses that practiced discrimination in downtown Jackson. He said he was beaten and ridiculed on numerous occasions for his activism in the Deep South — by both unruly mobs and police. Weeks after the Woolworth's clash he was seriously injured with a colleague when his car was wrecked in what he believed was a rigged automobile accident. He was also the subject of several smear campaigns and was surveilled by the FBI, which compiled a large dossier on him.

“It helps to have, as I have since the hatch, a thick skull and a thick hide,” Salter wrote on his website.

A life of activism and the classroom

Salter’s career was a mix of teaching and activism, which took him around the country. He organized several grassroots events on social justice, poverty, literacy, youth activity and labor and held teaching posts at Superior State College in Wisconsin; Navajo Community College (now Diné College) in Tsaile, Arizona; Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont; Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa; the University of Iowa; and the University of North Dakota. Salter also taught and developed courses for the American Indian Cultural Center at the Iowa State Penitentiary.

He retired as a full professor and former departmental chair from the American Indian Studies Department at the University of North Dakota, where he worked from 1981 to 1994. Salter changed his name in 1995 to John Hunter Gray to honor his Native American roots.

Salter moved to Pocatello, Idaho, after retirement and remained involved in various civil rights campaigns until his death.

"Mr. Salter's life and his actions remind us that turmoil around the rights of others is everyone's challenge. That he stood up — or, in this case, sat down — for the rights of others demonstrates courage and a commitment to justice," said Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, President’s Professor, director of the Center for Indian Education and ASU’s special adviser to the president on American Indian affairs. "While some may boil his activism down to this moment at the lunch counter, it is obvious that Mr. Salter spent his life engaged in acts of social justice. In so many ways, he embodies the spirit of the New American University by accepting the responsibility of helping create a better, healthier society. May he rest in peace and power."

Top photo: John R. Salter Jr. (seated left and in the foreground) helped organize the May 28, 1963, Woolworth's sit-in demonstration in Jackson, Mississippi. The civil rights activist was a product of Arizona State University, where he received his undergraduate in 1958 and a master's degree in sociology in 1960. Photo courtesy of the Jackson Daily News

More Law, journalism and politics

ASU's Carnegie-Knight News21 project examines the state of American democracy

In the latest project of Carnegie-Knight News21, a national reporting initiative and fellowship headquartered at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication…

Arizona secretary of state encourages students to vote

Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes looked right and left, taking in the more than 100 students who gathered to hear him speak in room 103 of Wilson Hall.He then told the students in the Intro…

Peace advocate Bernice A. King to speak at ASU in October

Bernice A. King is committed to creating a more peaceful, just and humane world through nonviolent social change.“We cannot afford as normal the presence of injustice, inhumanity and violence,…