Ants invented agriculture long before humans started watching 'ant farms'

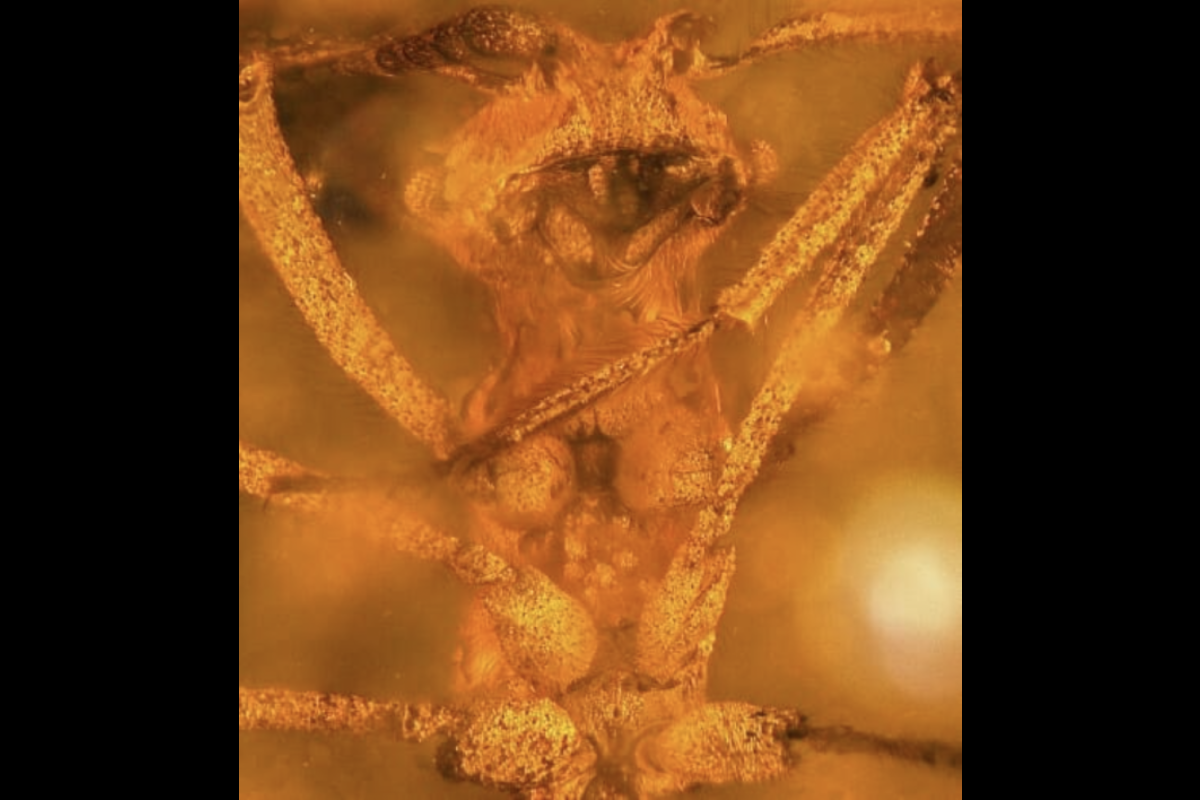

A fungus-farming ant is covered in white symbiotic bacteria, which the ant relies on to produce antibiotics to protect its garden from a parasitic fungus. Photo by Alex Wild

About 50 years ago, the first ant farms took off in popular culture, turning children into backyard scientists.

Turns out, a child’s natural curiosity would prove right: We could learn a thing or two about the world from studying ants.

Now, a team of scientists has shown that the invention of agriculture — by ants — happened some 50 million years ago. "Ant farmers" used the world’s first pest-control management in the form of antibiotics.

“Less than a century ago, humans learned to employ antibiotics for medicinal purposes, whereas ants have been using antibiotic secretions from bacteria to manage their fungus gardens for millions of years,” said Christian Rabeling, an assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences within Arizona State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The study appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was a result of a collaboration between ASU, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Smithsonian Institution, Harvard Medical School and the University of Sao Paulo.

Ants go marching two by two

The story begins in the New World, where 60 million years ago, a new group of ants, the fungus-growing or attine ants, emerged from the tropical rainforests of South America.

Attine ants love mushrooms, making them their sole crop to cultivate and care for. But like humans, ant farmers faced the threat of pests in the form of fungal parasites that could wipe out their harvests.

So, not long afterwards, the ants began marching in step with a symbiotic bacterium, called actinobacteria, that grows in clumps of stringy white patches on the ants’ exoskeletons in special, deep pockets. These pockets, known as crypts, could provide a home for the actinobacteria while the ants could use their antibiotics to spread on and protect their rich mushroom crops.

“The interdependence between ants, fungi and bacteria seems to be very strong, and in this study, we show that the ants repeatedly evolved special pockets on their bodies, so-called integumental crypts, that allow for keeping and feeding these antibiotic-producing microbes,” Rabeling said. “Considering that providing these crypts and nourishment to the bacteria is costly to the ants, we think that the benefit the bacterial antibiotics provide for the ant-fungus mutualism must be significant.”

Today, actinobacteria are the leading source of antibiotics in medicine, but 50 million years ago, ants figured out that by letting bacteria live on their bodies, they could protect their crops.

A beautiful friendship

Using new DNA data from a special ASU and Smithsonian collection of 69 ant species, the scientists traced back in time and found that the relationship was so important, it evolved three separate times in fungus-farming attine ant species.

“The crypts present on the ant's integument appear to be the key evolutionary innovation that allowed ants to acquire and host antibiotic-producing bacteria,” said postdoctoral researcher Jeffrey Sosa-Calvo, who helped reconstruct the ants’ evolutionary tree from field collections in far-flung Central and South American locations. “These bacteria have helped the ants to maintain their mutualistic association with their fungal cultivar for millions of years.”

Ant species who aren’t farmers lack these structures.

“This work provides fascinating insights into an animal using bacteria to provide antibiotics over a long period of time,” said Cameron Currie, a UW-Madison professor of bacteriology who has researched the dynamics of farming ants for decades.

Further evidence for the ancient origin of the ant-bacteria relationship came from a handful of fungus-farming ants fortuitously frozen in amber from what is now the Dominican Republic. Through the hardened tree sap, the researchers could spot the telltale signs of bacteria clinging to the ants’ bodies. With the amber dated to between 15 million and 20 million years old, the research team could validate their genomic data and show that the ant-bacteria symbiosis was at least as old as the amber samples.

But the crypts were not ubiquitous. Some species have lost any obvious structures for supporting bacteria. The researchers showed that ants that have done away with crypts have also lost any trace of symbiotic actinobacteria.

Putting the 'ant' into antibiotics

Some 10,000 years ago, humans first mimicked the ants’ farming lifestyle. Later, in the 20th century, people turned to actinobacteria for most clinical antibiotics. That the ants have, for millions of years, used similar antibiotics to protect their fungal gardens from pests suggests that we still might learn from their success.

Perhaps the ants may know best how to use their precious antibiotics to prevent the rise of antibiotic resistance — which has never occurred in ant colonies.

“I strongly believe there are mechanisms here that reduce the emergence of antibiotic resistance,” Currie said.

“I am always amazed by the complex symbioses that ants form with other organisms,” Rabeling said. “It will be exciting to study the interactions of fungus-growing ants with the highly diverse array of microbes in greater detail.”

Discovering what those mechanisms are might just help us extend the useful life of our own antibiotics.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants U19 TW009872-05, U19 AI109673, and DMR-1720415), the National Science Foundation (grants DEB 1456964 and 1654829), and the Sao Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP (grant 2013/50954-0).

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to…