A feature-length documentary has become a surprise hit at the box office and is renewing questions about adoption rights, privacy and related protections.

“Three Identical Strangers,” which has grossed more than $11 million in four weeks, is the story of a trio of strangers who accidentally discover they are identical triplets separated at birth. Their 1980 reunion at age 19 catapulted them to international fame, but it also unlocked a disturbing secret that transformed their lives.

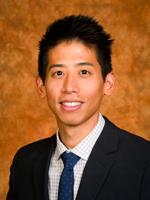

Kaiponanea Matsumura, an associate professor of law at ASU’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, called the circumstances of the adoptions in the movie “particularly egregious.” His research focuses on the regulation of marriage and nonmarital relationships. He teaches contracts, family law and a seminar on assisted reproductive technologies and the law.

Matsumura spoke to ASU Now about the new documentary, the complexity of adoption law and the need for confidentiality and anonymity.

Kaiponanea Matsumura

Question: The adoptions in the movie “Three Identical Strangers” took place more than a half century ago. How much has changed in terms of adoption laws?

Answer: The circumstances of the adoptions in the movie seem particularly egregious: There, children and their adoptive parents were intentionally kept in the dark about the fact that they were subjects in a controversial psychology experiment. Even outside those hopefully rare circumstances, however, the law generally attempts to protect the privacy of biological and adoptive parents and their children. In the 20th century, states began to pass laws making adoption proceedings confidential, keeping the identities of the parties private and denying access to birth records. These laws were motivated by assumptions about the need for confidentiality and anonymity.

For example, it was thought that the severance of all ties between the biological parents and adoptee would help the parents move on from the mistakes of their youth and also allow the adoptee to bond more completely with the adoptive parents. It would also give the adoptive parents the confidence that their family privacy would not be invaded by the biological parents or other members of the child’s original family. Although adoption laws vary from state to state, most states have retained most of these laws.

That said, social views about adoption are changing. For instance, most child-welfare professionals now favor disclosing a child’s adoptive status rather than hiding it. Adoptees often want to know more about their biological families. And even adoptive parents often want to know more information about the adoptee’s biological family and are growing increasingly receptive to open adoption. In response to these developments, states have begun to require adoption agencies to collect nonidentifying information about adoptees and their biological families and have made it easier for parties to petition for access to this information.

Q: The film shows that New York still has some of the most closed laws in the country. How can these laws be changed? Or should they?

A: New York was an early adopter of confidentiality laws, but it is not an outlier. Still, some states have made it easier for adoptees to find out information about their biological parents. Several, for example, now grant adult adoptees access to their original birth certificates without judicial approval. Others allow adult adoptees to view their sealed adoption records. Lawmakers have the power to change adoption laws. Whether they will is really up to them.

When deciding, they should weigh the needs and interests of the parties and also consider whether these changes will promote the goals of adoption, like placing children in good families. Most adoptees seem to favor access to nonidentifying, as well as identifying, information. But we might weigh that desire against the competing (and disputed) concern that eliminating strict confidentiality could deter people from adopting.

Movie poster for "Three Identical Strangers"

Q: Obviously, adoption laws are meant to protect children, but in many cases, the records are sealed from the same children when they become adults. Is there a reason for this?

A: To the extent that these laws were responding to the fear that information about an adoptee’s biological parents could disrupt the harmony of the adoptive family, that concern would live on beyond childhood. But those concerns certainly seem weaker once adoptees become adults.

Q: What do you think adoption confidentiality laws will look like in the future?

A: There seems to be a significant desire on the part of adoptees to learn more about their biological families. At the same time, adoptive parents seem to be more comfortable disclosing to their children that they are adopted. The rigid boundaries of the nuclear family seem less meaningful to most people than they once were. And people are more accepting of a variety of family forms. As such, I would expect that confidentiality provisions will loosen, especially once children reach adulthood. Moreover, the proliferation of affordable genetic-testing services and ancestry databases make it likely that adoptees will be able to find their biological families even without the help of the law.

I know adoptees who have found their biological parents this way. Part of me worries, however, that an emphasis on the importance of biological connections will obscure what to me is an even more important basis for family relationships: caregiving. I hope that laws that provide increased access to genetic information do nothing to denigrate adoption as a coequal means of forming a meaningful family relationship.

More Law, journalism and politics

How to watch an election

Every election night, adrenaline pumps through newsrooms across the country as journalists take the pulse of democracy. We gathered three veteran reporters — each of them faculty at the Walter…

Law experts, students gather to celebrate ASU Indian Legal Program

Although she's achieved much in Washington, D.C., Mikaela Bledsoe Downes’ education is bringing her closer to her intended destination — returning home to the Winnebago tribe in Nebraska with her…

ASU Law to honor Africa’s first elected female head of state with 2025 O’Connor Justice Prize

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first democratically elected female head of state in Africa, has been named the 10th recipient of the O’Connor Justice Prize.The award,…