Dietary competition played a key role in the evolution of early primates

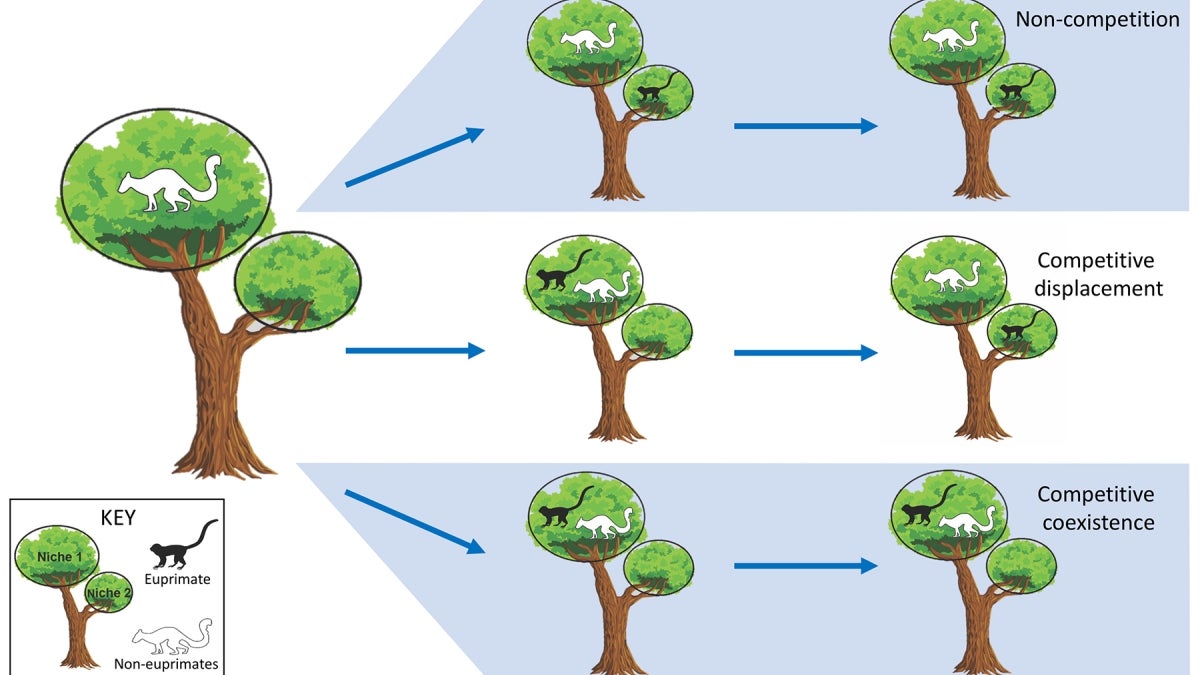

Three models of niche competition between euprimates and non-euprimate mammals. Non-euprimates thrived across North America prior to euprimate arrival about 55 million years ago (large tree, left). After euprimate arrival (center column), these two groups could have: occupied separate niches with no competition (top row, right); occupied the same niche with one group ultimately displacing the other to reduce competition (middle row, right); or coexisted with minimal competition (bottom row, right).

Since Darwin first laid out the basic principles of evolution by means of natural selection, the role of competition for food as a driving force in shaping and shifting a species’ biology to outcompete its adversaries has played center stage. So important is the notion of competition between species, that it is viewed as a key selective force resulting in the lineage leading to modern humans.

The earliest true primates, called “euprimates,” lived about 55 million years ago across what is now North America. Two major fossil euprimate groups existed at this time: the lemur-like adapids and the tarsier-like omomyids. Dietary competition between these similarly adapted mammals was presumably equally critical in the origin and diversification of these two groups. Though it has been hinted at, the exact role of dietary competition and overlapping food resources in early adapid and omomyid evolution has never been directly tested.

New research published online Tuesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B led by Laura K. Stroik, an alumna of ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change (SHESC) and currently assistant professor of biomedical sciences at Grand Valley State University, and Gary T. Schwartz, associate professor with SHESC and research scientist at ASU’s Institute of Human Origins, confirms the critical role that dietary adaptations played in the survival and diversification of North American euprimates.

“Understanding how complex food webs are structured and the intensity of competition over shared food resources is difficult enough to probe in living communities, let alone for communities that shared the same landscape nearly 55 million years ago,” Stroik said.

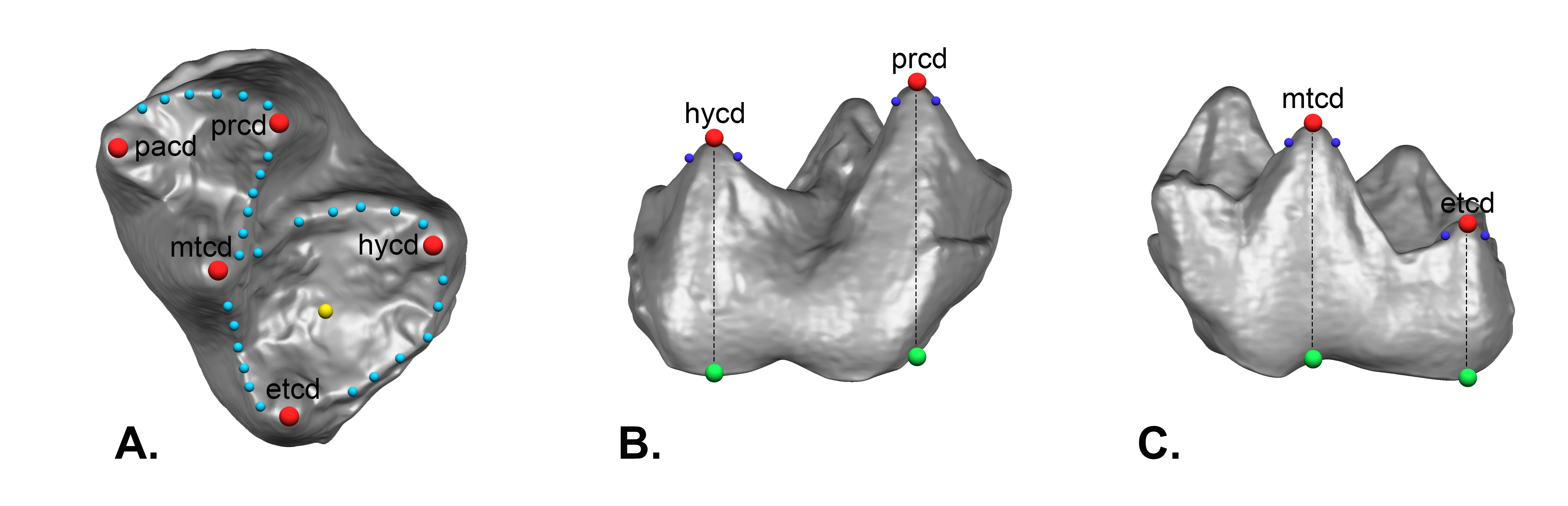

The researchers utilized the latest in digital imaging and micro CT scanning on more than 350 fossil mammal teeth from geological deposits in North America. They sought to quantify the 3D surface anatomy of molars belonging to extinct representatives of rodents, marsupials and insectivores — all of which were found within the same geological deposits as the euprimates and were thus likely real competitors.

The high-resolution scans allowed them to capture and quantify details of how sharp, cresty or pointy the teeth were. In particular, they looked at molars, or teeth at the back of the mouth, useful in pulverizing and crushing food or prey. The relative degree of molar sharpness is directly linked to the broad menu of dietary items consumed by each species.

Examples of micro CT scans of molars and the types of measurements researchers were looking at.

Stroik and Schwartz used these aspects of molar anatomy to compute patterns of dietary overlap across some key fossil groups through time. These results were then weighed against predictions from three models of how species compete with one another drawn from the world of theoretical ecology. The signal was clear: Lineages belonging to the adapids largely survived and diversified without facing competition for food. The second major group, the omomyids, had to sustain periods of intensive competition with at least one contemporaneous mammal group. As omomyids persisted into more recent geological deposits, it is clear that they evolved adaptive solutions that allowed them to compete and were usually victorious.

"The results showed adapids and omomyids faced different competitive scenarios when they originated in North America," Stroik said.

“Part of what makes our story unique is that for the first time we compared these fossil euprimates to a range of potential competitors from across a diverse group of mammals living right alongside adapids and omomyids, not just to other euprimates,” Schwartz said. “Doing so allowed us to reconstruct a far greater swath of the ecological landscape for these important early primate relatives than has ever been attempted previously.”

The key advance of this new research is the demonstration that diet did in fact play a fundamental role in the establishment and continued success of euprimates within the North American mammalian paleocommunity. An exciting outcome is the development of a new quantitative tool kit to diagnose patterns of dietary competition in past communities. This will now allow them to explore the role that diet and competition played in how some of these fossil euprimates continued to evolve and diversify to give rise to living lemurs and all higher primates.

More Science and technology

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your…

Large-scale study reveals true impact of ASU VR lab on science education

Students at Arizona State University love the Dreamscape Learn virtual reality biology experiences, and the intense engagement it…

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…