God bless the child: How religion built Billie Holiday’s inner soundtrack

Editor's note: You can listen to Tracy Fessenden's Billie Holiday Spotify playlist while reading this article.

The distinctive, melancholy voice; the floral accented hair; the lore of a life marked by lows, highs and lows again; the name Billie Holiday quickly conjures the personification of a jazz singer.

But what about religion? What were the spiritual drivers behind the singer’s songs, struggles and successes? It’s not a theme readily connected to Billie Holiday, but Tracy Fessenden believes religion shaped the woman her fans and friends called “Lady Day.”

Fessenden, the Steve and Margaret Forster Professor in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies at Arizona State University, explores the impactful but understated connection between religion and Holiday in her new book, "Religion Around Billie Holiday." She recently shared the discoveries of her research and writing with ASU Now — just in time for Jazz Appreciation Month.

Question: What inspired you to write a book about Billie Holiday and religion?

Answer: Six or seven years ago, my friend Peter Kaufman, a historian of European Christianity, invited me to write a book for a new series — “Religion Around” — which starts from the premise that we learn something valuable about an iconic figure by studying the religion around that person. I chose to write about Billie Holiday because her music has always haunted me, and I wanted to know how religion might have shaped her life and her sound. I also knew that I could listen to Billie Holiday night and day for the years I would spend writing this book, and never grow tired of her.

When students ask me why they should study religion, even if they are not religious themselves, I often tell them that religion is all around them, so studying religion is as important as studying any other aspect of their environment. Writing for the “Religion Around” series gave me a chance to put that answer to the test.

Tracy Fessenden

Q:What are some of the more surprising things you learned about the singer while researching and writing this book?

A: Between the ages of 10 and 12, Billie Holiday, then known as Eleanora Fagan or Elenore Gough, spent a total of about eleven months in a Catholic convent, the Baltimore House of the Good Shepherd for Colored Girls. Biographers have said very little about this period in Holiday’s life, and when they do mention it, the convent usually figures as one of the many hardships she endured. It was a place where girls whose parents couldn’t or wouldn’t look after them were placed by the courts, and where girls and young women who’d been caught up in sex trafficking were held in protective custody. But the House of the Good Shepherd is also where Holiday received her only formal vocal instruction. At daily Mass at the House of the Good Shepherd she sang liturgical chants in the minimalist melodic register she retained and perfected as a jazz singer.

While at the House of the Good Shepherd Holiday was also exposed to the stories of ancient and medieval women saints in the Catholic tradition who had made rich, complicated, venerated lives from their own, very punishing personal histories. She was schooled in their lives and taught to emulate them to develop a distinctive persona.

Q: How did religion shape and influence Billie Holiday’s music — the blues — which was often called “the devil’s music?”

A: Holiday could sing blues like no one else sang blues, but she wasn’t primarily a blues singer. In fact, she often resented that label, as though being black had landed her in that category by default. Blues or rhythm-and-blues, R&B, functioned as a catch-all category for black popular musicians until fairly recently, just as “race records” or “race music” was the catch-all designation for black musicians before that.

In the 1920s and '30s record companies made little distinction between religious and secular audiences in marketing race records. For their part, black religious records and blues conspicuously touted a divide between them — saved and sinning, sacred and profane, God’s word and the devil’s music. But both brought spiritual resources to the task of plain endurance in punishing circumstances.

Church songs tend to locate spiritual power in community, while blues songs find spiritual power in independence. One reason the distinction between the church and the devil’s music stuck is that blues came into being in murderous times, among those for whom church was still a place of relative safety. Every black church was a secular institution as well as a sacred one, insofar as it was a place where congregants could bring problems in search of this-worldly solutions.

Q: Billie Holiday’s life is often described as “tragic” given her death at such an early age. Is this a fair and accurate description?

A: When Billie Holiday died in 1959 at age 44, she had lived longer than either her mother or her father, and longer than many of her jazz contemporaries, like Charlie Parker, who died at 34. When we regard her life as tragic, I think we register the fierce wish that she had been spared some of what she survived: that she’d had a decent home life, that she hadn’t been earning her way as a prostitute by the age of 12, that she hadn’t been ravaged by heroin. Holiday’s tragic persona was also a part of her art, in the sense that it was an image she cultivated, and to some degree controlled. It was a way of giving voice to degradation and pain, her own and others. But at the same time, alongside this project and in it too, you hear a kind of resilience that is very hard won, never triumphal or glib.

Q: Holiday remains an important figure on the musical landscape almost 60 years after her death. Why do you think she still holds such a powerful impact?

A: It’s true; we could go into a Starbucks right now and hear Billie Holiday, and her voice wouldn’t sound like a nostalgia trip — it would sound very fresh and of the moment. She pretty much invented jazz singing, and everyone who has come after Billie Holiday has had to deal with that. The great composer and instrumentalist Ornette Coleman said that the difference between jazz on the one hand and rock and pop music on the other is that in the latter, everyone plays or sings to the beat of the drummer. But in jazz the drummer is one instrumentalist among others. So everyone playing jazz is more or less liberated from a fixed beat in metronomic time.

Billie Holiday figured that out very early in her career, the first vocalist to do so, and she changed music as a result. Other vocalists in the big band era sang along to the band. Billie Holiday was with the band, one instrumentalist among others, and also separate from the band. She really was the first true jazz singer. No one singing or playing jazz escapes her influence. If all philosophy is a footnote to Plato, all jazz is an implicit riff on Billie Holiday.

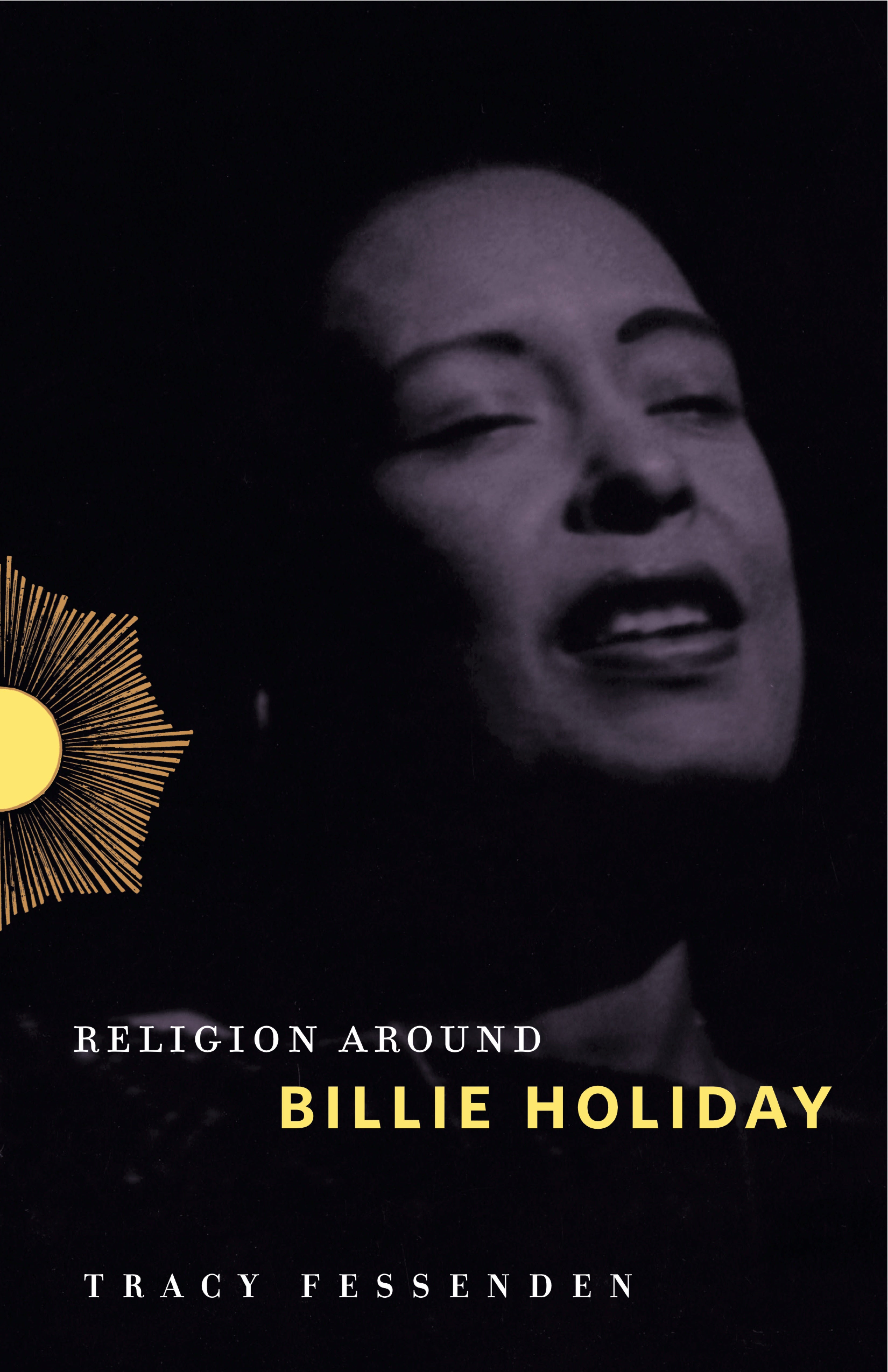

Fessenden's book "Religion Around Billie Holiday"

Q: What do you hope readers will come away with after reading "Religion Around Billie Holiday?"

A: I hope people will gain an appreciation of the influence on Billie Holiday of Catholic liturgical music and Catholic understandings of confession and forgiveness, of the Jewish songwriting culture of Tin Pan Alley, of the echoes of black church sounds in the blues she heard and sang in brothels. That’s the “around” part of Religion Around. But music, like religion, isn’t just ambient; it’s also something we carry inwardly. I think almost everyone has an inner soundtrack. We all have songs in our heads. And spirituality is a kind of inner soundtrack, a set of inner grooves. So more than anything I hope readers of this book will be moved to listen to Billie Holiday and to listen inwardly, so that we have her music in our heads as we go about tending the world and making our lives.

Tracy Fessenden’s book “Religion Around Billie Holiday” is available now through Amazon and Penn State University Press.

Top photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

More Arts, humanities and education

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…

Upcoming exhibition brings experimental art and more to the West Valley campus

Ask Tra Bouscaren how he got into art and his answer is simple.“Art saved my life when I was 19,” he says. “I was in a dark place and art showed me the way out.”Bouscaren is an …