ASU launches inaugural Lab Safety Innovation Award

Mitch Magee is a researcher in the Biodesign Institute. Photo by Jason Drees

After receiving his doctorate in microbiology in the 1980s, Mitch Magee, now a researcher in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, began studying tuberculosis (TB) in a lab on the East Coast. Because TB is a highly infectious, airborne disease, the lab purchased a centrifuge tool with a special lid to keep the bacteria from getting in the air.

“We were smart. We knew what we were doing. We were covering all our bases,” explained Magee. The team grew some TB bacteria for six months and conducted their experiments.

A year later Magee had to get a TB skin test to make sure he hadn’t been exposed to the disease. With the test, an extract of TB bacteria is injected in your skin, and if you’re infected you get a little red bump the size of a small marble.

Magee’s bump was three times that size.

He called his boss and they had everyone in the lab tested. Three other people were infected.

“One of them actually had a lesion on her lung. She had active tuberculosis. So they had to go test all of her family. Her little brother had an active lesion on his lung. So they had to go test all of his junior high school class,” Magee said. Fortunately, the infection stopped there.

Magee shared this story at the launch of ASU’s inaugural Laboratory Safety Innovation Award on Dec. 6. He was selected as the event’s keynote speaker for his commitment to safety in his lab.

Inaugural award for safe science

The award is sponsored by ASU’s Laboratory Safety Committee in partnership with the offices of Knowledge Enterprise Development and Environmental Health and Safety. It is designed to encourage safe research practices and showcase ASU’s commitment to safe science. The committee will issue awards annually to ASU researchers who have implemented innovative safety programs.

The awards include a monetary prize. Applications are due by Feb. 22.

Learn more about ASU’s Laboratory Safety Innovation Award

“At ASU, the commitment to the responsible and safe conduct of research is a shared responsibility led by principal investigators, supported by university leadership and fostered by the University Laboratory Safety Committee,” said Deb Murphy, director of research operations and senior compliance advisor within KED. “The USLC, a standing committee reporting to the provost through KED, is comprised broadly of the disciplines and campuses of the university and is charged with promoting a strong safety culture for research and academic endeavors at ASU.”

Magee said he learned early in his career that even when something gets written into the standard operating procedure, people may not always follow the rules.

After a yearlong investigation by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, his previous lab figured out that one of the technicians hadn’t been using the special centrifuge lid. Without it, the bacteria likely got in the air, and later into the lungs of the affected people.

“Sometimes people get lax. You have to make sure your procedures are being followed. If you write them, you have to follow them,” he said.

Safety is still key for Magee

Magee knew he wanted to work with infectious disease since his sophomore year in college, when he started studying the immune response of rabbits to bacteria. For decades he has worked with tuberculosis, valley fever and influenza — all diseases that can infect with a single breath. Because of this, his lab is certified as a Biosafety Level 3 lab, meaning it has highly specialized, exhaustive safety measures built in to protect workers.

Magee, who also leads Biodesign’s Laboratory Safety Committee, says his goal is not just to meet all of the safety requirements, but to exceed them. For example, he requires people working in his lab to wear special efficiency particulate respirators to filter the air they breathe, even though it isn’t technically required by safety regulations.

“With research, the neat thing is that we’re finding something better,” Magee said. “We’re finding a better way to diagnose disease. We’re finding a better method to do a test or analysis. We’re finding a better way to do whatever we need to do.”

He finished his speech at the award kickoff by arguing that safety is the same thing.

“With safety, there’s always a better way," he said. "You just don’t know it yet."

Safely finding a better TB test

Today, Magee is an assistant professor of research in Biodesign’s Virginia G. Piper Center for Personalized Diagnostics. He still studies TB and is working to develop a TB test that is easier, faster, less expensive and more accurate than current methods.

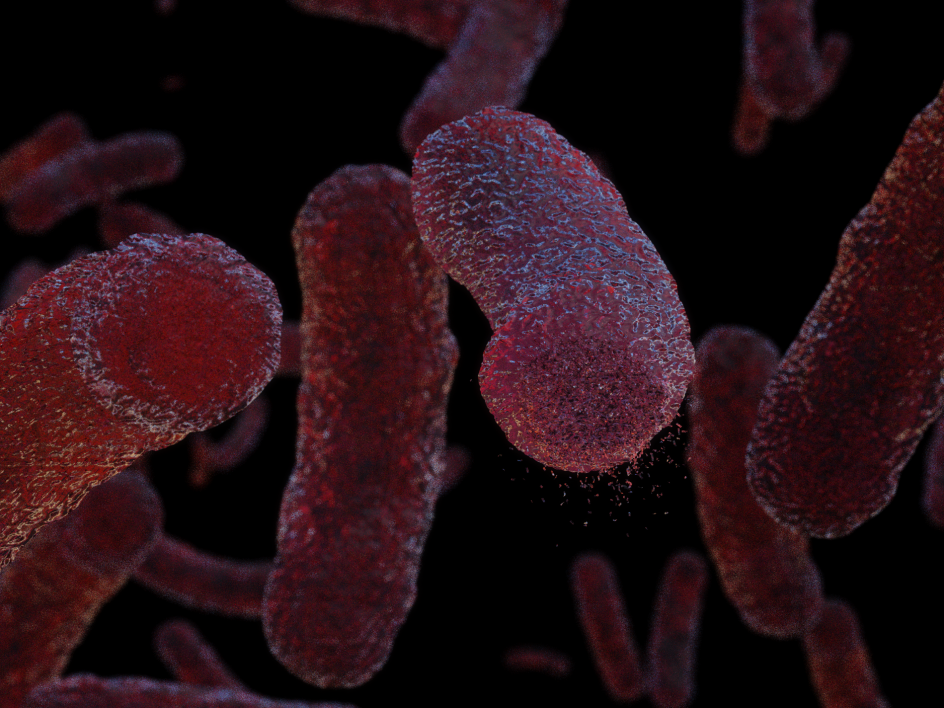

With nearly one-third of the world infected with tuberculosis, it’s no surprise the disease is remarkably easy to catch. A person with TB can cough out tiny droplets teeming with bacteria. By inhaling just 10 of those bacteria flying through the air, a person nearby can be infected in a single breath. The bacteria start boring a hole in that person’s lungs, the coughing begins and the cycle continues. It is estimated that nearly two million people die of TB each year.

As with most diseases, the earlier TB is diagnosed, the better. Treatment is much easier during earlier stages of the disease, and early treatment can help keep TB from spreading. But early diagnosis is a challenge.

Tuberculosis bacteria. Illustration by Jason Drees

Doctors can detect TB infection with a skin or blood test. However, not everyone infected with TB will develop the disease and become contagious. The current method for diagnosing TB disease is to culture a sample of mucus (sputum) coughed up from deep inside the lungs. Unfortunately, these samples can be difficult to collect and the cultures take a long time to produce results. They also have a high false-negative rate.

Rather than looking for TB bacteria, Magee’s method looks at how the body responds to the bacteria. When your body is infected with a disease, your immune system creates proteins called antibodies that help to neutralize the disease. Antibodies are extremely specific and target proteins produced by the disease.

“The antibodies can be indicative of one disease state over another. Maybe like latent versus active tuberculosis. The ability to detect antibodies to tuberculosis could help provide a better test to identify tuberculosis patients,” said Magee.

He is able to identify the right antibodies using a technique called High Definition Nucleic Acid-Programmable Protein Array (HD-NAPPA), developed by Joshua LaBaer, director of the Center for Personalized Diagnostics and executive director of the Biodesign Institute.

So far, Magee has identified 40 different TB proteins that could potentially serve as biomarkers to detect the disease. Now he’s working on validating all 40 and picking out five or six robust ones to use for his diagnostic test.

“We could take a serum sample from a patient, and in about 15 to 20 minutes ask, ‘Do they have antibodies to these key proteins?’ They would know that day that they have tuberculosis,” said Magee.

Not only would this test be faster, but it would also be more accurate than the current sputum test, which can miss bacteria that haven’t grown fast enough. This gives the test an edge when diagnosing people that have both TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), because HIV can make TB bacteria even harder to detect. This could prove particularly helpful in the developing world, where TB and HIV are both prevalent and diagnostic resources are limited.

Magee’s research on TB is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). One of his most recent grants supports research comparing TB patients in the United States and South Africa over time. South Africa has one of the highest rates of HIV in the world.

"The ability to detect antibodies to tuberculosis could help provide a better test to identify tuberculosis patients," said Magee.

Written by Sabrina Leung

More Science and technology

Brilliant move: Mathematician’s latest gambit is new chess AI

Benjamin Franklin wrote a book about chess. Napoleon spent his post-Waterloo years in exile playing the game on St. Helena. John…

ASU team studying radiation-resistant stem cells that could protect astronauts in space

It’s 2038.A group of NASA astronauts headed for Mars on a six-month scientific mission carry with them personalized stem cell…

Largest genetic chimpanzee study unveils how they’ve adapted to multiple habitats and disease

Chimpanzees are humans' closest living relatives, sharing about 98% of our DNA. Because of this, scientists can learn more about…