Thanksgiving brings us closer together, but our conversations across generations in a family can sometimes drive us farther apart.

“We’re forced to spend these long hours with people, some of whom we may not like very much, and that is stressful,” said Vincent Waldron, Arizona State University intergenerational communications professor.

It’s rare for all generations, from the silent generation to boomers to Gen Z, to find themselves in one room. According to Waldron, our main hindrance is that we don’t “ask interesting, meaningful questions and we’re OK with just superficial small talk.”

So we’ve compiled some intergenerational complaints and probing questions you might hear at the table and given an ASU expert the chance to give you some talking points to keep the peace and understand your family more.

“How’s your love life going?”

It’s not nosiness per se but a biologically driven question, according to evolutionary biologist Michael Angilletta.

“There’s this thing called parent-offspring conflict where offspring just want parents to keep taking care of them as much as possible and parents want to be able to take care of more than just one child and then take care of themselves,” he said.

“The conflict can tie to love life, too, because you know if someone is in a stable relationship they’re on their way to forming a stable partnership, which ultimately leads to grandkids — and I’m going tell you that’s one of the greatest biological drivers of our behavior, right?”

“Back in my day, we didn’t have these high-tech gizmos …”

There can be a generational gap in technology, but it’s important to remember that technology isn’t inherently a smartphone, but even a wheel or lever, according to historian Christopher Jones.

“The grandparents of boomers grew up in a world with little plumbing, no electricity and almost never traveled faster than the pace of walking, but their grandkids flew in planes, drove in cars, lived in electrified homes with good plumbing,” Jones said.

“It’s a recurrent pattern that people assume they are living through radical technological innovation of the types not seen before.

“These changes — experienced on a daily basis — made a far greater difference in terms of personal comfort, convenience and health than anything Silicon Valley has generated in the last generation and were quite disruptive in their own day to those living through these technological transformations.”

But according to counseling psychologist Ashley Randall, there is something known as technoference, where even the mere presence of a cellphone, as long as it’s within view, “decreases your perception of the quality of the social interaction.”

“Put your cellphone away and allow room for the cranberry sauce instead,” Randall advised.

“Younger kids, you’re just not working hard enough.”

Much like boomers can’t retire like their parents’ generation, many younger Gen Xers and millennials don’t have the same relationship with work their parents did, according to Pamela Stewart, a senior lecturer in history and Osher Lifelong Learning Institute lecturer.

“Part of the reason a younger generation is looking for that satisfaction and not only a paycheck is that to some degree they observed people that they thought had stable jobs lose them,” she said.

“If you could potentially end up losing a job then maybe you should be able to get some job satisfaction along the way.”

“I don’t understand your texts. Why can’t you write in proper English?”

It took until the Renaissance for dictionaries with prescribed spellings and usage to appear, said linguistics professor Elly Van Gelderen. And some historical texts, such as the 15th-century Paston family letters, are as hard to read as some of your children’s texts.

In that context, van Gelderen suggests that a little textual ambiguity shouldn’t be painted as the demise of grammar and spelling.

“Texting doesn’t seem to have a standard, and that’s why it reminds me of the Middle Ages,” she said. “In between 1100 and 1500 you have no standard so people just write the way they think they speak. In the moment, texting has given people the freedom to not be so prescriptive, and by prescriptive I mean following these silly rules.”

“You kids and your selfies.”

It’s not just the latest generation that’s self-obsessed. Art historian Corine Schleif points out that middle class and wealthy patrons painted themselves into the foreground of pictures of salvation history, including the birth of Christ or the Crucifixion.

“It’s a way to immortalize yourself, as portraits are, and in a sense with a selfie, too,” she said. “There was that kind of empathy that was developed through this kind of imagery, and I think that happens with selfies today.”

So if a friend takes a picture of herself in an important place, Schleif said she can relate to that in a different way than if she were just to open a magazine or look on the internet for a picture.

“You know you get that from your Uncle Johnny.”

They might be hard to deal with and Thanksgiving might be all the time you’d like to spend with family, but for computational biologist Melissa Wilson Sayres — who works on interpreting DNA — family is as much based in our real-life relationships as our genetic ones.

“Your genetics don’t define you; it’s the people around you and the people you interact with,” she said. “What if you’re adopted, right? It’s still the person you grew up with and probably share your microbiome with. Your complaints about your parents and your nosy cousin and all of this stuff, it’s just so much more important than genetics — and I say that as someone who devotes my life to genetics.”

Top photo: Holiday postcard from 1914. Images courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections, wikimedia and publicdomainpictures.net.

More Science and technology

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…

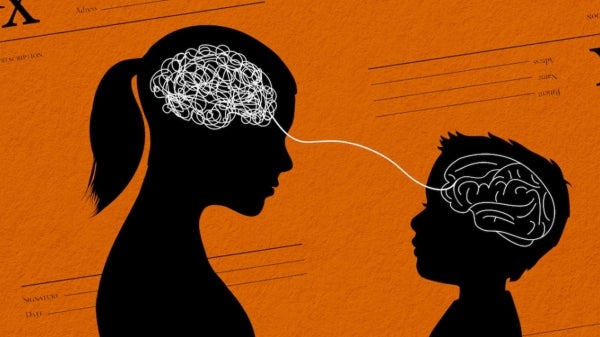

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking risks, having a hard time resisting temptation, difficulty getting…