Real 'Mission Impossible': Thwarting hackers with individuals' biosignals

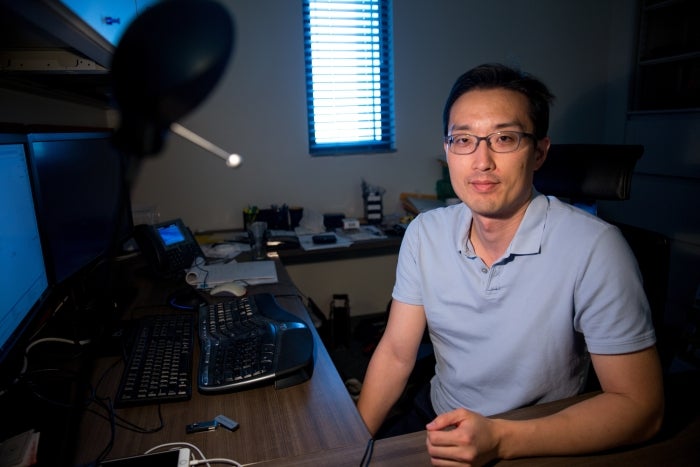

Professor Jae-sun Seo holds an ECG authentication chip in his hands. Seo hopes to use chips like this in wearable devices such as Apple watches to create biometric security measures based on electrical activity of heartbeats. Photo by Anya Magnuson/ASU Now

At a cinema in the not-too-distant future …

The deputy defense minister sprints down a street in Vienna. His smart watch contains missile blueprints.

Ethan Hunt rappels from a building, tackling the minister and slipping the watch from his wrist. Hunt inserts a contact lens printed with a high-res photo of the minister’s eye and holds the watch to his face.

No luck. It really is a mission impossible. The watch’s data is protected by authentication tied to the minister’s heartbeat. Hunt can’t fake that. He’s been thwarted by Arizona State University researcher Jae-sun Seo’s biometric security measures.

Seo, an assistant professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, was the lead on a pair of studies that developed security authentication based on electrical activity of heartbeats, or electrocardiogram readings.

While few of us have intercontinental ballistic missile blueprints on our Fitbits, they do contain medical information. Sensors pick up your electrocardiogram and other signals. That’s private medical data.

Your medical information is worth 10 times what your credit card is on the black market, according to the FBI. More data breaches happen in the medical and health-care industry now than in other sector, including financial, education and government, according to the nonprofit Identity Theft Resource Center. Health-insurance information can be used to purchase drugs or medical equipment, which are then resold illegally, or even to get medical care.

Tech companies are constantly stepping up security measures. Besides passwords, fingerprints, retinal scans and facial-recognition software are popping up in the latest gadgets.

“Still there is some vulnerability,” Seo said. “Fingerprints can be hacked. Iris, sometimes if you have a high-resolution photo it can be unlocked. ... In that sense multi-factor authentication becomes really necessary. To that extent we have been working on a different biometric modality, namely our physiological signals such as (electrocardiogram).”

The tech — a chip — developed by Seo and his colleagues stresses the individuality of electrical heartbeat signals.

“What we are proposing is that we can actually perform user authentication with our own (electrocardiogram) signals, and we can actually generate random secret keys using our own signals as well,” Seo said. “What that means is that although signals might look very similar from person to person, they are actually different. ... If you look at them visually, they don’t look that different. That’s where our technology comes in. We perform sophisticated filtering, signal processing and employ relatively simple neural networks to extract features, which are maximally different between different individuals.”

How would it work? One of Seo’s sensors on the back of the watch might touch your skin and pick up your physiological signals.

“It could continuously authenticate and make sure the owner is wearing the device instead of an adversary who stole the device and is trying to do something with it,” he said.

Another advantage is that it’s nonintrusive. No typing a password 10 digits long or rubbing your sweaty thumb on the screen or posing your face in an unnatural fashion.

Although the core technology is still in the research phase, Seo said it could be integrated into other tech, like phones or security systems.

“We have developed prototype chips and demonstrated real-time (electrocardiogram) authentication with very low power, which enables seamless integration into wearable devices,” he said. “Getting into a product will mean much more validation and verification of quality assessment. There’s still a way to go, but we verified our custom prototype chip with a fairly large database of more than 600 people.”

Shihui Yin was the student lead on both papers. The work was in collaboration with Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in Korea.

More Science and technology

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your health history in five-inch stack of paperwork fastened together with…

Large-scale study reveals true impact of ASU VR lab on science education

Students at Arizona State University love the Dreamscape Learn virtual reality biology experiences, and the intense engagement it creates is leading to higher grades and more persistence for biology…