Editor's note: This is the first in a three-part series that came from a search through history for Sun Devil war heroes. Today, we meet a pair of soldiers killed in World War I.

We all know the story of the most famous Sun Devil killed in combat — Pat Tillman, the gridiron star who left a lucrative and comfortable NFL slot to die for his country as an Army Ranger in Afghanistan.

But the stories of others have been lost to history. The past was so murky that for decades it was believed that Howard Draper, killed overseas in September 1918 during World War I, was the first ASU war hero to make the ultimate sacrifice. But new research shows that Albert Pitts died in battle about a week earlier just 30 miles away.

The ongoing search into ASU's military past has revealed a story filled with stories.

It’s a story of patriotism. Similar to Tillman, Pitts and Draper voluntarily joined a fight that others avoided.

It’s a story of the unexpected. In the kind of bizarre twist only the truth contains, Pitts and Draper probably passed right by each other in France — twice.

It’s a story of Arizona. At the start of World War I, five years after statehood, the former territory now sat at the federal grownups table, wearing adult clothes and trying not to misbehave (like Huck Finn living at the Widow Douglas’ house).

It’s a story of growth. The young Tempe Normal School, which wouldn’t become Arizona State University for about half a century, was learning to respond to world events, as it does now.

And it’s a story of America. For the first time, the nation became involved in a large-scale foreign war. It was a reluctant engagement. The nation was peopled by immigrants who had fled the kaiser and tsar and had no wish to send their children back across an ocean to fight them.

This is their story, and ours.

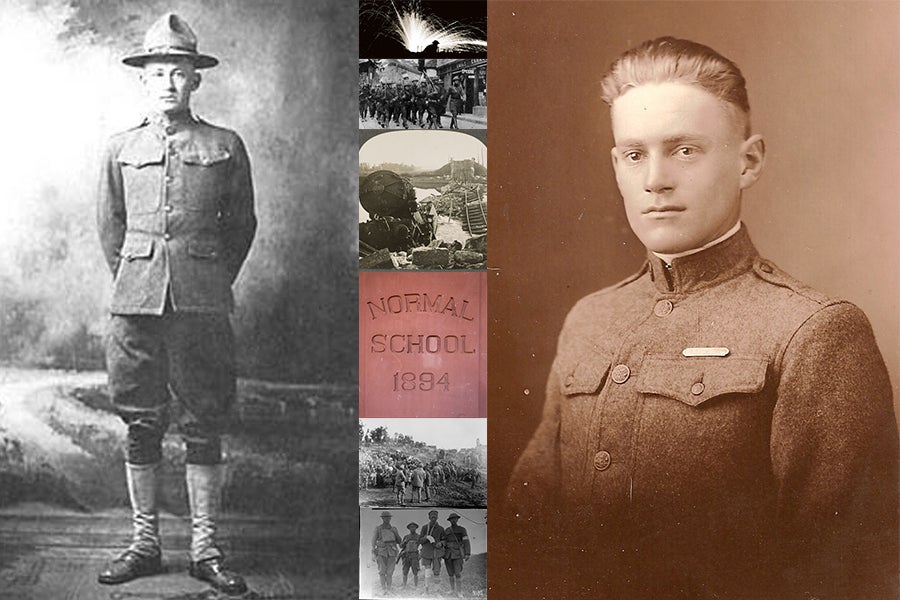

Albert Pitts (left) and Howard Draper (right).

Pitts and Draper: Different, yet the same

Albert Pitts and Howard Draper were about as different as could be for two men from the same place and the same time.

Draper was a strapping, square-jawed country boy who wears the same stony expression in all his photos — a farmer’s trait.

Pitts was a skinny, sharp-faced, jug-eared kid who could talk birds out of trees. He was never going to stay on the ranch where he grew up.

There are similarities, however. Neither graduated. Both appeared in newspapers of the day. Pitts for setting fire, delivering a speech and singing in an opera. Draper for trapping bobcats and coyotes, suing a neighbor and portraying Lincoln in a debate, despite making “no endeavor to impersonate” the president, the Arizona Republic wrote at the time.

They also were both patriots, in the same vein as Tillman.

“Volunteers like them were the exception, not the rule,” said ASU historian Heidi Osselaer.

The National Personnel Records Center has few service or medical records from this era. A fire in 1973 destroyed details for Army personnel from 1912 through 1959. Everything in this story is pieced together from interviews, newspapers, letters, military histories and university archives.

In history, one only gets the grain that’s left on the threshing-room floor.

Pitts, an irreverent and skillful writer

Albert Pitts, the son of a well-to-do rancher and nephew of a U.S. senator, was by all accounts a complete and utter wiseass.

Consider his classmates’ impression. An unattributed line in the 1917 yearbook, called the Saguaro, reads, “Albert Pitts possesses the strangest mind known to man.”

Pitts was born in Flagstaff in 1893. By the time he left for the war in 1917, he had established himself as a witty and skillful amateur writer.

In November 1908, he spoke at a political rally in Phoenix. He was 15 years old. “The address of Master Pitts was easily the feature of the evening,” the Arizona Republic reported. “He spoke for probably twenty minutes, his remarks having been prepared without assistance and made an address full of good points, witty and entertaining. There was more than one candidate on the stage, thrice his age perhaps, who would have given a good deal could he have made as good an impression on the audience as did the young man.”

He graduated from Central School in Phoenix in 1909, reciting a famous poem from the era, “The Contest in the Arena.” He appeared in the press several times that year.

In March, his eighth-grade class demonstrated at the Legislature in support of a bill that would prohibit cigarettes in the territory. “The bill was read in the house by Albert Pitts ... whose boyish though determined voice carried the earnestness of the young campaigners,” the Republic reported. In April, the Republic ran a short mention when his family threw him a surprise party. In May, he sang as part of the supporting cast in the opera “Bohemian Girl.” (The Coconino Sun called it a “winner.”)

The next year, 1910, when he was 17, he accidentally set the kitchen on fire when his parents were away. He lit an oil lamp without a glass chimney on it, and the flame set a kitchen towel ablaze. Neighbors watering their yard put the flames out. (A loss to history is his explanation to his parents about what happened.)

Pitts’ uncle, U.S. Sen. Henry Ashurst, was among those who recognized his potential. “He writes a fine letter and philosophizes remarkably well for a boy of his age,” Ashurst wrote in a 1918 letter.

Pitts was on track to become a lawyer. He left Tempe Normal School in 1912 to work as a secretary for an Arizona Supreme Court judge. (One suspects his uncle being a U.S. senator had something to do with that job.) After three years, he enrolled in the University of Michigan law school. He enlisted from law school, ending up assigned to the 125th Infantry, a Michigan regiment since the Civil War and today a regiment of the Michigan National Guard.

The writing skills his uncle praised and the irreverence his classmates pointed out carried to his time in the military. Pitts’ letters home from France — printed in the Tempe Normal Student newspaper and the Coconino Sun as “Letters From Coconino Boys ‘Over There’” — are full of stories about stealing food, shirking office work and insulting the French.

It’s amusing to think of Pitts as a college student. If he raised that much hell in war-torn France, he must have cut quite a swath on campus.

Draper, earnest and hardworking

Howard Draper came from a mining family.

As a young teenager, he lived in Sayers, a halfway stop that catered to miners between Wickenberg and Constellation. Today, it’s a ghost town.

The 13-year-old Draper hunted and trapped to earn money. The Prescott newspaper reported in 1910 that he had been paid $23 in bounty by Yavapai County for 20 skunks, a coyote and a cat. (In today’s dollars that would equal almost $550.) Three months later, he was paid a similar bounty for 16 skunks, six “wild cats” and a coyote.

Late in 1911, young Draper was in court. He had accused one Allen Cameron of poisoning his dog. Dogs and coyotes were killing Cameron’s goats, so he spread poison for 3 miles around his house. Cameron was found guilty and fined $50.

In 1914, when Draper was 17, he won an essay contest sponsored by the Northern Arizona Fair Association. The topic was: “How the Northern Arizona Fair Can Best Help My County.”

Beyond that, we don’t know much about Howard Draper from history. Interviews help fill in the blanks.

“I was named after him,” said his namesake Howard Draper, a nephew who today lives in Modesto, California. “What I’ve read about him … he really impressed these people who wrote about him all those years later.”

Any letters Draper wrote are lost to time, his nephew said. But in some ways the surviving records tell us all we really need to know.

The bounties earned show him as a hard-working kid. Taking Cameron to court showed that Draper had a strong sense of right and wrong that he believed in standing up for. That he went to court in a Wild West era where violence was common shows that he had a respect for authority and believed in American institutions such as the justice system.

Draper made his way to Tempe as a young man because he was smart and wanted an education. Then he put country ahead of self at a time when almost no one else wanted to. In that era, no one would have spoken ill about him if he chose to stay home and help out or continue his education. Miners at the time, said Osselaer, the historian, “were chanting things like, ‘Down with the draft.’ They were of the mentality that this was the rich man’s fight … I was surprised to see (Draper) was from that sort of background.”

Draper’s story is full of uncommon choices.

“Living in mining communities … it was not a great place to raise children,” Osselaer said “It was tough. You were constantly trying to keep the kids from not encountering the drunks out of the saloons or laying on the ground Sunday morning, prostitutes and other things. It could be very hard on a woman trying to raise a family and dealing with these characters who were really rough. But she was married to a miner, and that was her lot in life.”

Howard Draper the Sun Devil wasn’t born in Arizona. His mother, Martha Draper, went home to Gloster, a tiny town in southern Mississippi, to have all three of her children. “My grandmother didn’t like the doctors in Arizona,” Howard Draper, the nephew, said of his namesake's mother. “She did that for all three of her children.”

Draper had every opportunity to fall in with a bad crowd, drink, gamble and raise hell. But he didn’t. It sounds like a Sunday school parable, but it’s true. Clearly Albert and Martha Draper are to thank for that. They raised their son in mining camps, places so rough-hewn and transient that barely anything remains of them today. And they raised a really good kid.

Tempe Normal School

Pitts enrolled in the Tempe Normal School in 1910, according to ASU archivist Robert Spindler.

There is a bit of a mystery to his movements. He dropped out of the school (a lot of students did then), but he is also mentioned in the 1917 Saguaro yearbook. There’s probably a simple explanation, but it’s lost to history.

Draper enrolled in 1915, according to the Matriculation Register. He was the 2,214th person to enroll in the school. Most students were from Arizona. About 1 in 10 were from the Midwest.

In 1910, 11,000 people lived in Phoenix. Tempe had 2,500 inhabitants. It was relatively inexpensive to attend the school, so students came from a wide variety of economic backgrounds.

“It was a very small school, in a very rural place,” Spindler said. “We drew very well from Arizona. … We were still offering free tuition for students who would teach in the Arizona public schools, but we were beginning to recruit effectively out of California and other parts of the United States.

“And when you look at the catalog, the language of the catalog is very much intended to demonstrate that this is a well-established school of quality education and children would be safe here. In 1918, people are still remembering the frontier, and for a kid to grow up in Chicago or New York to come out here was a pretty big deal. And as a parent, you might be worried about that. So, if you look at the language of the catalog, they go out of their way to talk about modern facilities, and we were up to 13 buildings at that point. It was really an amazing thing. You know, we grew very quickly.”

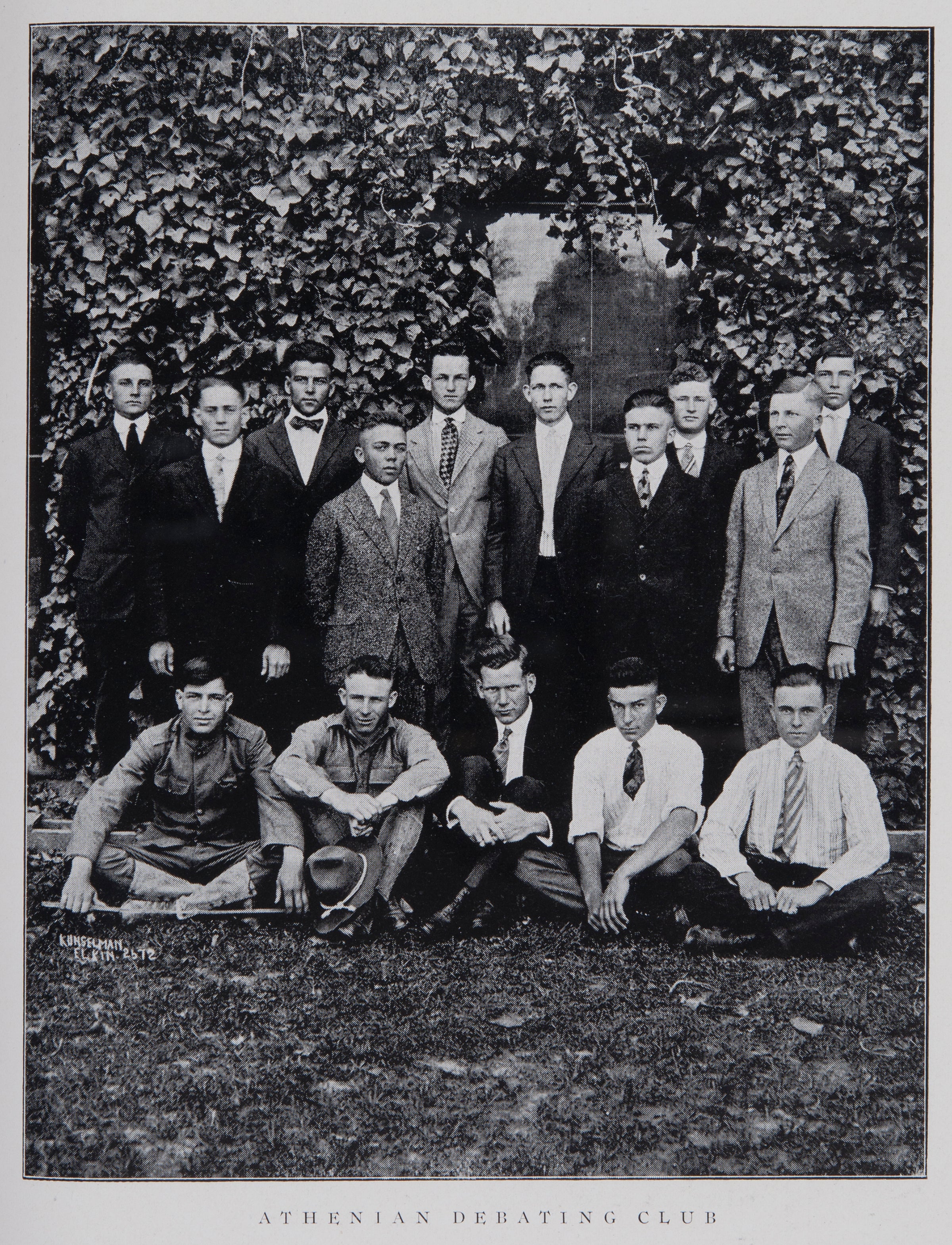

Draper was a member of the Athenian Debating Club. On Lincoln’s birthday in February 1917, the club reenacted the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Draper played Lincoln.

“The speakers made no endeavor to impersonate the famous men they were representing, but they did give a most interesting research into American history,” the Arizona Republic reported.

The next item in the paper was about a man who had been kicked by a horse.

Searching for Sun Devil war heroes

Part 1: Pitts and Draper: Different, yet similar

Part 2: An unpopular choice to enlist

Part 3: Life — and death — at the front

Top photo: An exploding phosphorous round silhouettes a helmeted American doughboy of the 28th Division at Fismette in August 1918. The French-ordered attack was a costly failure. Photo courtesy of the National Archives

More Law, journalism and politics

Native Vote works to ensure the right to vote for Arizona's Native Americans

The Navajo Nation is in a remote area of northeastern Arizona, far away from the hustle of urban life. The 27,400-acre reservation is home to the Canyon de Chelly National Monument and…

New report documents Latinos’ critical roles in AI

According to a new report that traces the important role Latinos are playing in the growth of artificial intelligence technology across the country, Latinos are early adopters of AI.The 2024 Latino…

ASU's Carnegie-Knight News21 project examines the state of American democracy

In the latest project of Carnegie-Knight News21, a national reporting initiative and fellowship headquartered at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication…