An Arizona State University neuroscientist is helping a private company develop a brain implant that will help the blind to see.

Intended for use by people without a retina — the largest segment of the blind population — the device is expected to enable the blind to see light and shapes and, in a best-case scenario, allow them to read a large-print book.

Bradley Greger, an associate professor in the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, is working with a California company on a cortical implant.

Second Sight Medical Products makes a retinal prosthesis that is on the market in 12 countries. It works by converting images captured on a miniature video camera mounted on glasses into a series of small electrical pulses. The pulses are transmitted wirelessly to an electrode array implanted on the retina.

The pulses stimulate the retina’s remaining cells, giving the perception of patterns of light. Patients learn to interpret the patterns, gaining some useful vision.

The implant Greger is working on is for people born without a retina, or whose retina was destroyed by cancer, trauma or glaucoma.

“What I’m doing is helping them do is take that technology to a cortical implant,” Greger said. “Some people just don’t have a retina. ... I’m taking their technology and expanding it so where we can go straight into the visual cortex of the brain and then get those people to see. It’s a much larger segment of the blind population.”

The cortex is much bigger than the retina, freeing up space to attach the implant. The retina is much smaller, and workspace, so to speak, is limited.

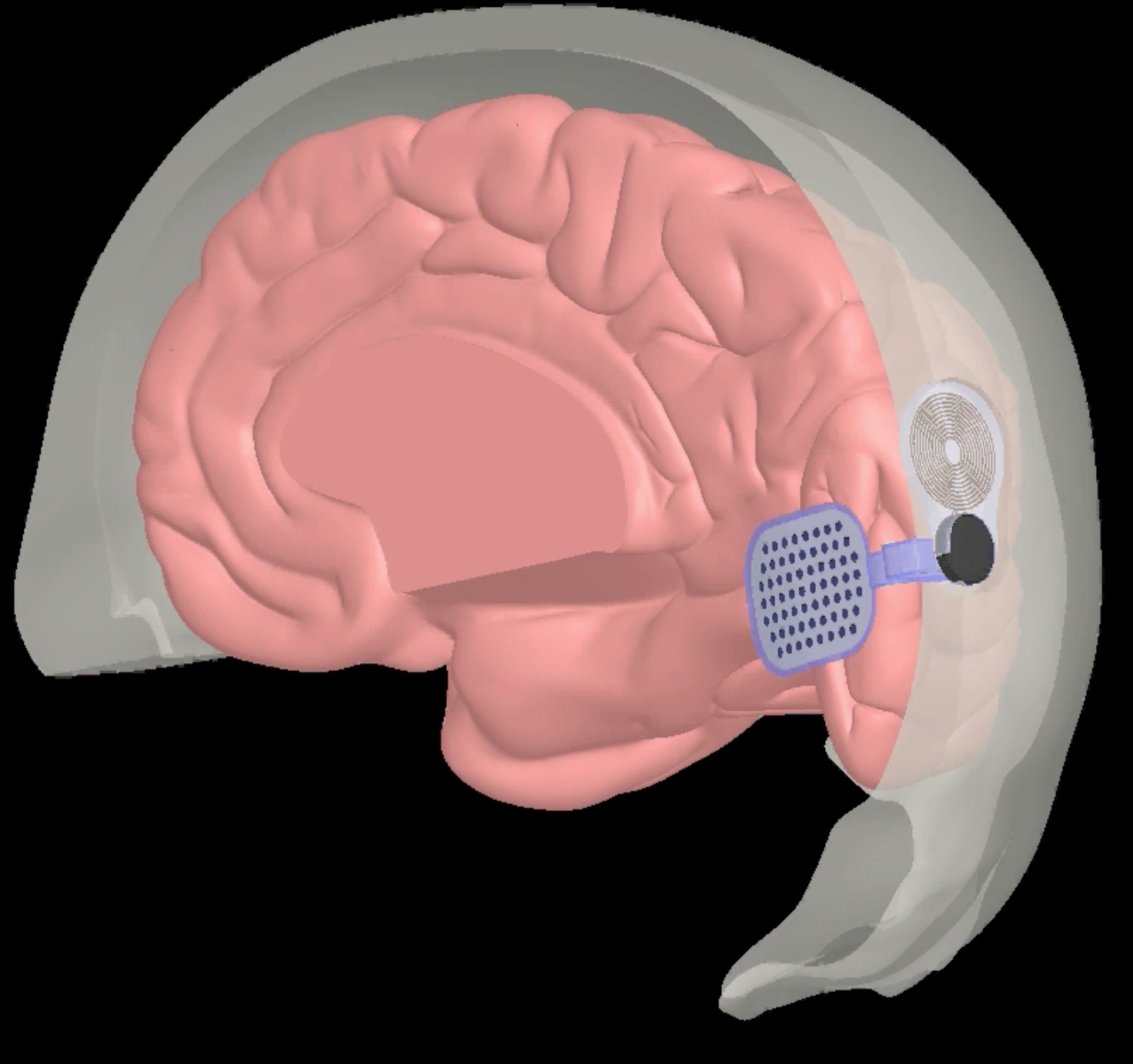

Designed for people without a retina, the device would be implanted directly on the visual cortex. Because the cortex is much larger than a retina, the developers are hoping to achieve a better, more detailed result. Image courtesy of Second Sight Medical Products

“That’s one of the things we’re helping to sort out,” Greger said. “Can we really restore better vision by going into the cortex versus the retina? ... It’s a larger target, so we can get more electrodes per visual angle. We’re hoping to get a little bit better; maybe they could read a large-print book. That would be awesome if we could get that sort of thing.”

Ken Spector was born with cancer and blinded at a very early age. A program coordinator for Alternative Format Services with ASU’s Disability Resource Center — he specializes in Braille — Spector said, “It’s something I’d be interested in trying.”

Within a large portion of the deaf community, being deaf is considered part of their identity, and not something they would want to change through surgery or a device.

In the blind community, “I think it’s less pronounced,” Spector said.

“In the deaf community, there are those who feel that way, but it’s a very broad spectrum; there are hardliners and more moderates,” he said. “The same holds true in the blind community, but there’s a much smaller percentage of the blind community who would be of that mind-set. There would be some who would be against it based on being of the philosophy that they should be satisfied with what they are. But there are others who would want to try it because it’s a new technology. I’m sure there would be quite a few who would be interested.”

Greger’s role with Second Sight is as a research collaborator.

“They’ve put about 15 years of work into this and about $100 million,” he said. “I did not do this on my own. ... We’re helping them do some research and expand the applications for their product. ... It does have to be redesigned for the cortex, and we’re helping them work that out, how to do that optimally.”

Greger estimates Second Sight will push for a clinical trial in the next year or two. The company announced a successful trial implant in a 30-year-old patient in October, providing the first human proof of concept.

The patient was implanted with a wireless multichannel neurostimulation system called the Orion I on the visual cortex and was able to perceive and localize individual spots of light with no significant adverse side effects.

“It is rare that technological development offers such stirring possibilities,” Dr. Robert Greenberg, chairman of the board of Second Sight, said in a press release. “By bypassing the optic nerve and directly stimulating the visual cortex, the Orion I has the potential to restore useful vision to patients completely blinded due to virtually any reason, including glaucoma, cancer, diabetic retinopathy or trauma. Today these individuals have no available therapy, and the Orion I offers hope, increasing independence and improving their quality of life.”

Top image: A still from an animation showing the implant's placement. Image courtesy of Second Sight Medical Products

More Health and medicine

College of Health Solutions alumnus named Military Medic of the Year

By Keri Hensley and Kimberly LinnJonathan Lu has looked out for the health of his fellow military service members his whole career, starting with his role as a combat medic in the U.S. Army.Driven by…

ASU, Mayo Clinic forge new health innovation program

Arizona State University is on a mission to drive innovations that will help people lead healthier lives and empower health care professionals to develop novel new health solutions. As part of that…

Innovative, fast-moving ventures emerge from Mayo Clinic and ASU summer residency program

By Georgann YaraIn a batting cage transformed into a custom pitching lab, tricked out with the latest in sports technology, Charles Leddon and his Mayo Clinic research teammates scrutinize the…