Globe-trotting virus threatens tomato crops

Arvind Varsani, a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics, has been tracking the global spread of the disease-causing tomato yellow leaf curl virus.

Tomatoes, prized for their delicious taste and high nutritional content, are one of the most important crops grown around the world. In recent years, however, tomatoes have come under assault from a persistent and aggressively spreading pathogen.

Known as tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), the microbe has undergone rapid expansion from its humble origins in the Jordan Valley in the Middle East. Today, TYLCV devastates cultivated plants in both tropical and subtropical regions and has proven particularly difficult to control. It can often cause 100 percent destruction of tomato crops.

Arvind Varsani, molecular virologist at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics, has been tracking the global spread of this disease-causing virus, which is usually transmitted by an insect vector, Bemisia tabaci, better known as the silverleaf whitefly.

Varsani’s global search for novel and persistent viruses has taken him to remote regions of the world, where he has catalogued the presence of these tiny entities in everything from desert sands to Antarctic permafrost — a viral landscape of almost unfathomable richness, of which less than 1 percent has so far been explored. (Viruses, unlike bacteria and other members of the microbial world, do not have a universal gene, rendering them difficult to classify.)

Safeguarding the global food supply from disease-causing pathogens is a growing challenge. Habitat loss around the world is improving conditions for viral transmission and evolution as varied species come in closer contact. Keeping pathogens in check will require better techniques for identifying these viruses and managing global epidemics.

In a study recently published in the journal Virology, Varsani and his colleagues provide the most detailed accounting to date of the metamorphosis and spread of TYLCV. Their results highlight the challenges involved in controlling the virus, given the rapid emergence of variants able to survive targeted pesticides and outwit tomato varieties bred for resistance — the two mainline approaches used to combat the disease.

“It is impressive to see how quickly TYLCV has spread across the world from its most probable ‘tropical hub’ in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean region,” said Varsani, who is also an associate professor in the School of Life Sciences. “Furthermore, despite the strong quarantine regulations in place in various countries such as Australia, there have been multiple introductions of TYLCV. In general, geminiviruses are known to have high mutation rates and are highly recombinogenic, allowing them to explore sequence space rapidly.”

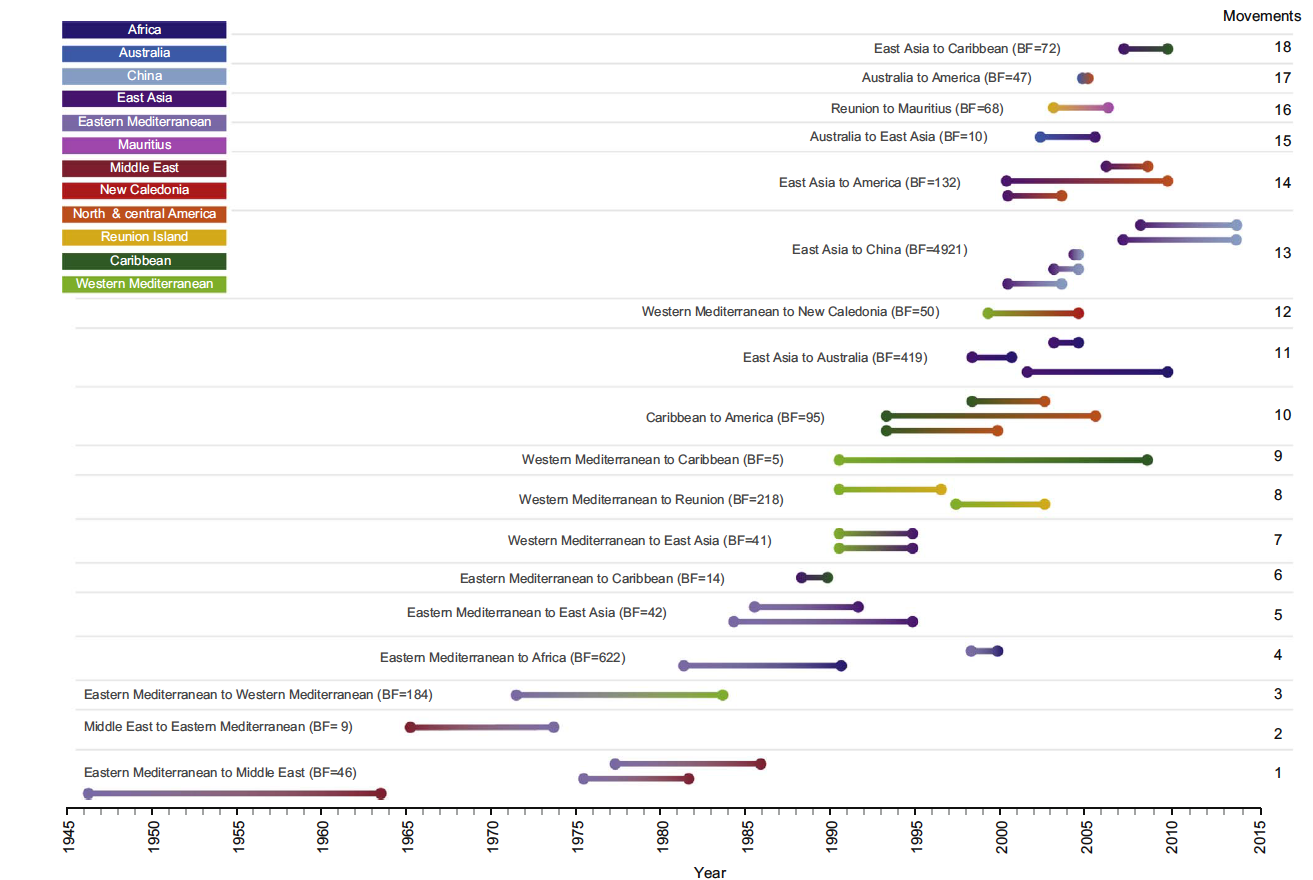

This graph shows the timing of historic movements of the tomato yellow leaf curl virus between the 12 regions analyzed in the study. The color gradients in each line show the potential movements from the ancestral variants of the virus (on the left of the line) to the migratory destination (represented by the color on the right of the line).

As the study notes, TYLCV is established in many tomato-growing regions of the world and continues to spread to new regions around the Indian and Pacific oceans including Australia, New Caledonia and Mauritius. The research provides a time-sensitive analysis of all publicly available, full genome sequences of TYLCV, together with 70 new genome sequences from Australia, Iran and Mauritius.

Viral mileage markers

Viruses provide excellent tools for monitoring evolutionary change over time and across geographic expanses, due to their rapid mutation rates and fast generation times. The current study makes use of this fact, exploiting a technique known as phylogeographic analysis to understand the origins and distributions of different viral strains.

Phylogeography produces evolutionary trees that combine genetic data with spatial information. Drawing on the increasing availability of genetic and geospatial data, phylogeography has also been used to track the global dissemination of many important disease-causing pathogens in humans, including viruses responsible for dengue fever, rabies, influenza and AIDS. Subtle alterations in viral genetic sequence can act like identifying fingerprints that offer information about where the particular strain originated and how rapidly it has evolved.

Mathematical models integrating spatial data on pathogen evolution with information on vectors, plant movements and environmental variability can provide researchers with vital clues helpful in managing disease epidemics in plants and animals including humans, while also advancing fundamental knowledge of evolutionary and ecological processes.

A tomato’s worst adversary

TYLCV is a circular, single-stranded DNA virus belonging to the family Geminiviridae. It is the most destructive member of a related group of pathogens causing tomato yellow leaf curl disease (TYLCD). While it is typically spread by an insect vector, recent research has shown that unlike other viruses of the same genus (Begomovirus), TYLCV is also seed transmissible. This fact, combined with the rapid development of resistant variants, has presumably led to TYLCV’s brisk migration and tenacious persistence.

The study results indicate that the first viruses belonging to the TYLCV strain likely arose in the Middle East between the 1930s and 1950s. They were not identified until the early 1960s and probably began their global conquest in the 1980s, when two strains, TYLCV-Mld (mild) and TYLCV-IL (Israel) spread outward from the Jordan Valley.

An outbreak in the eastern Mediterranean may have provided the virus with its first opportunity to spread to the rest of the world, eventually arriving in most tropical and subtropical regions and earning the distinction as one of the most devastating plant pathogens.

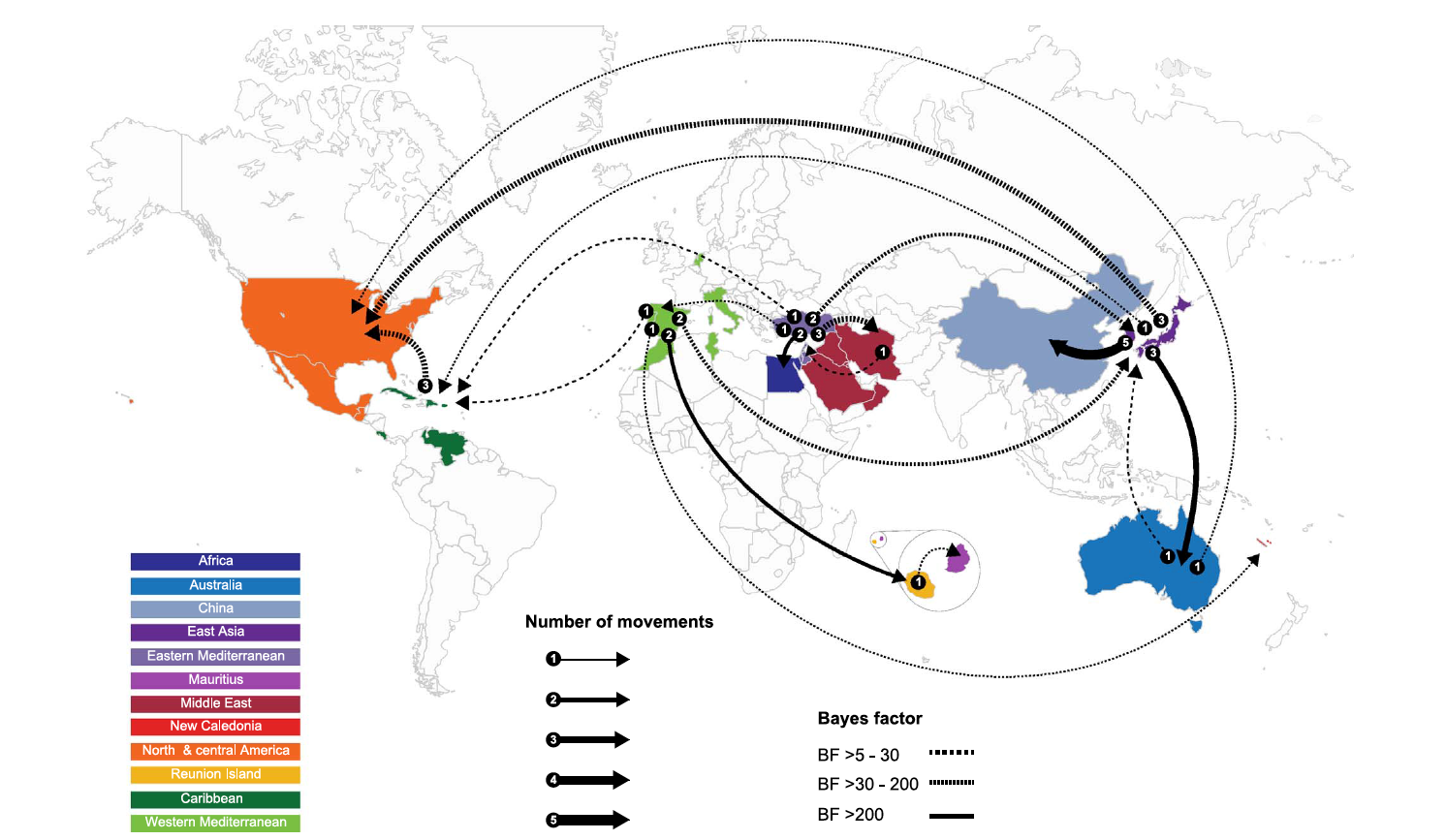

The map shows the global migration patterns of the tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Eighteen epidemiological links between 12 geographic regions identified in the study are displayed. The thickness of the lines represents the number of independent movements between locations. Dashed and solid lines indicate the "Bayes factor" — a measure of probability based on the gathered data.

Although seven major strains of TYLCV have been identified, only TYLCV-Mld and TYLCV-IL have ever been identified outside of Iran, the epicenter of TYLCV activity. (The diversity of TYLCV in Iran may be due in part to the climate, which has warmed and dried in recent years, creating conditions highly conducive to the whitefly carriers of the virus, though these fast-evolving strains are not considered a global threat at present due to epidemiological isolation of the region.)

As the study notes, the Mediterranean basin is the likely staging area for global movement of TYLCV. TYLCV-IL and TYLCV-Mld have the broadest geographical ranges of any TYLCV strains, and their dominance stretches in the Old World from Japan in the east to Spain in the west and the Indian Ocean island of Reunion and Australia in the south.

Presently, the virus is aggressively spreading into North and South America. The problem is partly due to ubiquitous international trafficking of crop varieties, though among geminiviruses, the geographical range — particularly of TYLCV-IL — is uncommonly broad. This highly invasive strain appears to have been introduced to the Americas, once from Australia and at least thrice from East Asia.

Infection sequence

While some notorious viruses (influenza, Ebola, HIV) may be spread through aerosol transmission or bodily fluids, many viral pathogens infecting plants and animals require a vector to pierce protective flesh or abrade plant tissue in order to introduce the viral particles or virions into cells. TYLCV is one such virus, requiring an insect intermediary to complete the infection process.

The disease is transmitted by the silverleaf whitefly, which acquires the virus after feeding on an infected plant for 15-30 minutes. After a latent period within the insect of 18-24 hours, the virus will be transmissible and a single whitefly may infect multiple plants. Large swarms of whiteflies can move between crops, causing rapid and far-reaching devastation. Some evidence suggests whiteflies may be able to pass on the virus to offspring, though this remains speculative.

Symptoms of viral infection by TYLCV include stunted plants with affected leaves showing curling, discoloration and deformation. The younger the plants are at the time of infection, the more severe is the reduction in yield.

Over long distances, the virus is primarily spread through the movement of infected plants. Since symptoms can take up to three weeks to develop, infected specimens often go unnoticed. Whitefly carriers of the virus also often hitchhike with plants, providing another means of long-range viral migration.

Evading resistance

Viruses like TYLCV can mutate rapidly. When two or more variants of the virus enter plant cells, they may swap portions of genomes, known as recombination. Through recombination, viruses aggressively shuffle the genetic deck, in the process producing novel strains capable of outwitting hybridized plant resistance.

Using phylogeography, Varsani and his colleagues describe in detail the complex variables affecting past and present-day global migrations of TYLCV. While epidemics in Australia and China are the likely result of multiple independent viral introductions from the East Asian region around Japan and Korea, the New Caledonian epidemic is derived from a variant from the western Mediterranean region and the Mauritian epidemic by a variant from the neighboring island of Reunion. Research suggests that intercontinental scale movements of TYLCV to East Asia have temporarily ceased, while long-distance movements to the Americas and Australia are likely ongoing.

Varsani notes that a better understanding of transmission dynamics and global pathways of migration will be required in order to develop better methods of control. Conditions for viral transmission are rapidly changing as humans come in greater contact with each other and with habitats harboring pathogens and global travel speeds up viral transmission and evolution.

At the same time, ancient viruses may be poised to re-emerge as environmental conditions change; for example, the exposure of unknown viruses locked in permafrost and released due to global climate change — another area of active research by Varsani and his colleagues.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…