Director Damien Chazelle’s hit musical “La La Land” has been nominated for 14 Oscars, tying the mark for the most in Academy Award history.

It comes just weeks after the film snagged a record seven Golden Globes, praise that keeps the spotlight on Chazelle and the often-overlooked musical genre. It also gives ASU Now an opportunity to return to our conversation with Desiree Garcia, director of film and media studies at ASU, and the star of Chazelle’s first film, 2009's “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench.”

In the following Q&A, Garcia discusses what it was like to work with Chazelle, the history and function of the musical in American culture and why “La La Land” has resonated so strongly with audiences.

“We’re in a period where a lot of Americans feel very uncertain,” Garcia said, recently.

“‘La La Land’ speaks to this moment in a very unique way, in a way that only the musical can,” by providing “beauty, art, hope and social acceptance.”

(Also, listen for her voice in the opening number of “La La Land.” A car is playing a song from “Guy and Madeline,” Garcia said.)

Desiree Garcia

Question: What was it like working with Damien Chazelle on his first film?

Answer: “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench” is an original musical that he wrote and filmed.

His idea was to meld a Hollywood musical — the classic “Singin’ in the Rain”-style musical — with a grittier, black-and-white documentary approach, which is very nonmusical.

So the germ of the idea sounds very strange, but what he ended up producing was something that felt quite modern at the same time that it harkened back to an earlier era. We didn’t have script, so a lot of it was improvised on the fly. Both me and my co-star Jason Palmer were nonactors. I think Damien wanted nonprofessional actors in the film so that it felt documentary-like, yet still had these glorious moments of song and dance. And in the end, it works quite well.

I would basically kind of show up and play myself. Damien would call me in the evening or the morning and ask if he could follow me wherever I was going that day. So I’d be going to the graduate student office to read a book, or I’d be walking downtown the streets of Boston on my way to a fabric store, or to get coffee.

It felt very organic, except for the musical numbers, which were highly orchestrated. For one number, we spent all night shooting at a restaurant where we could only shoot after it had closed, so we went all the way to 5 or 6 in the morning.

One of the things I really appreciate about Damien is that he has this almost scholarly, intellectual position about musical film. He’s thought about it very seriously, how it functions in society. He merges his love for the genre with a very educated understanding of how musicals function and why they work or don’t work.

Q: “La La Land” and “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench” are very different. What does it say about Chazelle’s abilities as a director that he’s capable of producing both?

A: They are remarkably different in style and tone but really quite similar in story.

The story lines have a lot of parallels. They’re basically these “boy and girl” stories where the girl is a waitress who’s aspiring to be a star, and the boy is a jazz musician who is struggling for his art. And the crux of the film is their relationship, whether or not they’ll be able to make it work in a modern, contemporary society.

Damien has said that he started thinking about “La La Land” about six years ago, which puts it right around the time “Guy and Madeline” was made. So the germ of “La La Land” was there.

He’s an incredibly risky filmmaker. He wants to be known for all kinds of film, beyond just the musical. I believe he’s working on a film about John Glenn, so that’s very nonmusical. When he first went to LA after “Guy and Madeline,” he was even working on some horror stories. So he’s very versatile.

Q: You’re the author of the 2014 book “The Migration of Musical Film: From Ethnic Margins to American Mainstream.” How did the role of the musical differ depending on the time period and the audience?

A: One of the things I was interested in with this book was why musicals appealed to audiences at specific times.

I was also interested in the relationship between what Hollywood was doing with the musical genre at the same time other filmmakers were making musicals outside of Hollywood.

There were Jewish filmmakers making Yiddish films and African-American filmmakers making films outside of Hollywood, largely because they had to at that time. And Mexican filmmakers were making musical films for Mexicans living in the U.S. — Spanish-language films that spoke to a diasporic Mexican population.

What I found is that all of those films were doing something quite different from what Hollywood was doing in the 1930s and '40s.

The former films were about community, and fostering tradition in the face of change. It makes sense because those communities were undergoing great transitions at that time, adjusting to new societies, new languages, etc.

So the musical served them very differently than the Hollywood musicals that featured Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in a boy-and-girl story. So this book was my attempt to historicize the musical. When we say “musical,” we’re talking about a very diverse group of films that have very different kinds of ideological problems depending on the time and the audience.

Q: Was there a golden age of musicals?

A: In the context of Hollywood, there most certainly was. Music came in right around when sound came in to Hollywood, about the late 1920s.

Scholars have pointed to the golden years of the musical as being roughly the same time as the golden age of Hollywood. So about the 1930s through the 1940s and '50s, when you had “Singin’ in the Rain,” and “The Wizard of Oz,” and films like those.

Q: Why do you think “La La Land” resonates so well with audiences? Do you think it has the potential to breathe new life into the musical genre?

A: Most certainly. One of the things that makes it so remarkable is that it is an original film musical.

The musical has never really died. It comes in fits and starts. It’s never really been absent from the screen. In the 1960s, Hollywood became very conservative with the musical, where instead of making original musical films, they were borrowing musicals from Broadway and elsewhere, where they have already been proven successful. That’s why in the 1960s you see “The Sound of Music” and “West Side Story,” which had already proved to be box office successes. …

That has largely remained the same up until now, with “La La Land” as an example. That’s one of the reasons it’s so exciting and why people are paying attention to it, because it’s been a very long time since original musicals have been made specifically for the screen.

“La La Land” is a very cinematic production. It’s the kind of film that would be hard to imagine moving to the stage because it’s so cinematic. There are things done with the camera, with editing, with sound, that just can’t be replicated onstage. So it’s a uniquely filmic product.

The musical has always done especially well in times of crisis in our society. It had its first moments of success during the Great Depression, where you had things like Warner Bros.’ “42nd Street.”

In the 1970s the musical did some interesting things, reflecting the darker moments of the recession with films like “Cabaret” and “Saturday Night Fever.”

Now, we’ve just gone through this horrific election cycle; we’re in a period where a lot of Americans feel very uncertain. “La La Land” speaks to this moment in a very unique way, in a way that only the musical can.

One of my pet peeves is that the musical is often referred to as an escape, as this highly unreal experience. My problem with that is it ignores the function of the musical, which is that it offers something to the audience that they’re lacking in their everyday lives.

It’s not what they’re running away from, it’s what they’re running toward: The musical provides beauty, art, hope, social acceptance.

In “La La Land,” there’s this great opening number, where everybody gets out of their car on an LA freeway and sings together, and they all feel as one for a moment.

That’s something that the musical provides that we’re not feeling right now. Some people are feeling alienated or marginalized, so the musical functions to provide us with something that fulfills us rather than allows us to escape reality.

Q: Do you have any favorite musicals from recent years, or can you point to any that have similarly resonated with contemporary audiences?

A: In recent years, I really like what John Carney is doing.

He made the film “Once,” which is an Irish musical, roughly around the same time as “Guy and Madeline,” which it is often compared to. It’s very bare-bones, low-budget feeling, and there are two people who come together and make music.

Carney has followed that theme with his second film, “Begin Again,” which is also about the process and joy of making music in a community. He also did “Sing Street” in 2016, which is set in the 1980s in Ireland, and it’s about a group of young boys who start a band and make music together.

He’s doing something very different than Damien; he’s exploring how people make music, and why, and what kinds of things come from it, what meaning it has in our lives.

I really appreciate what he’s doing, just as much as what Damien is doing, which is throwing all caution to the wind and making these musicals where you don’t need a stage, you don’t need to know where the music is coming from, you can just burst into song at the drop of a hat.

So they’re very different styles, but both are keeping musicals alive.

Q: You’re working on a book called “Show People: American Identities on the Musical Stage.” Tell me about it.

A: I’ve been working on this book for about a year.

My interest in this book is the role of the musical stage, the role that it has played in American popular culture. Not just film but theater, television, literature and radio; to see where this idea about the musical stage as being the place where you can go and work hard and eventually become a star, where that idea came from.

It’s the idea behind “American Idol,” the idea that anyone can be discovered and become a star in American society. I want to trace that idea back as far as I can to find out why it developed and how it developed.

I’m also interested in who was allowed to access that success at specific historical moments. In the early 20th century, that narrative almost applied exclusively to young, white women. They could rise from the ranks of a chorus girl to be a star and marry a prince or something. Then after WWII, African-Americans began to be included in that rags-to-riches narrative onstage. So I’ll be exploring all of that.

Top photo: Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling dance in "La La Land." Photo by Dale Robinette

More Arts, humanities and education

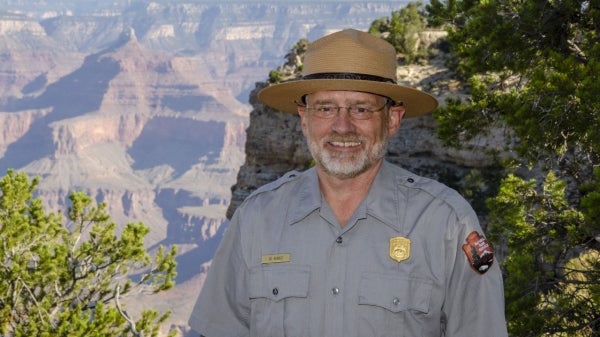

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…

Honoring innovative practices, impact in the field of American Indian studies

American Indian Studies at Arizona State University will host a panel event to celebrate the release of “From the Skin,” a collection over three years in the making centering stories, theories and…