Throughout all the ages of man, there has been a particular type of person who asks the same question.

Fur-clad early modern humans asked it as they pushed east across the rock and ice of the Bering Strait. Burton and Speke asked it as they crossed the East African veldt in search of the source of the Nile. Magellan couldn’t think about anything else, even if his terrified crew only thought of turning back. Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins asked it as they sailed to the moon across the great gulf of space.

“What’s over there?”

The two missions selected by NASA recently — one entirely run by Arizona State University, the other carrying an ASU-built instrument — embody that question, which is the essence of exploration.

That thrill of venturing into the unknown was palpable in Lindy Elkins-Tanton’s voice during a NASA teleconference announcing the two picks to fly, one a visit to a metal world, the other to study six primitive asteroids.

Strip away the modifiers, and the institution’s ultimate purpose stands starkly stated: the School of ... Exploration.

“This mission will be true exploration and discovery,” said Elkins-Tanton, the director of ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration and principal investigator of the Psyche mission. “Our job is to make the biggest discoveries possible.”

NASA officials, usually the epitome of understated cool, even let excitement creep into their statements.

“Lucy and Psyche will take us to worlds we’ve never seen before,” was the first thing Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said. “With every mission, we learn about the solar system.”

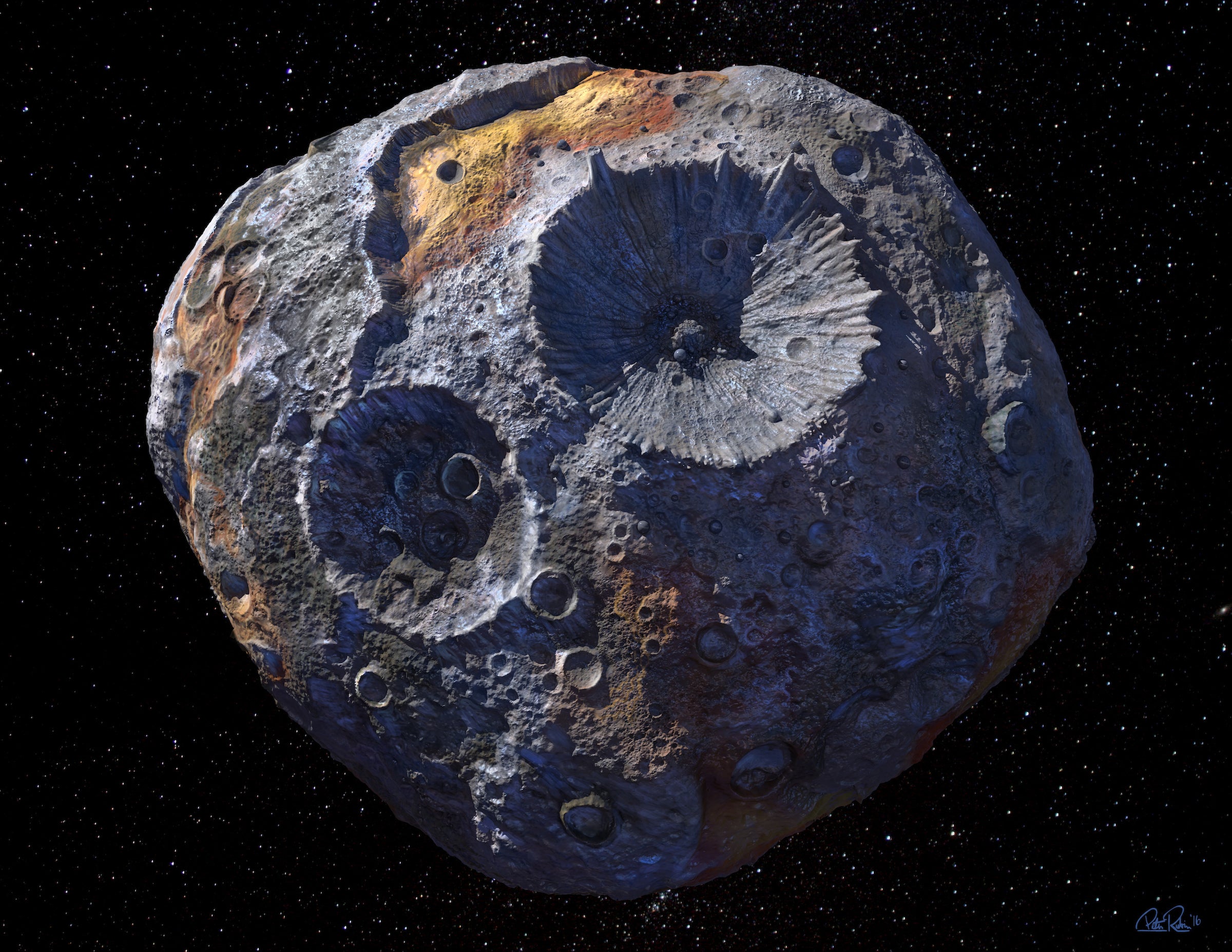

Artist rendition of the asteroid Psyche. Image by Peter Rubin/ASU

But why? Why leave Earth and home to spend hundreds of millions to go out into the black void of space?

Elkins-Tanton took a stab at the answer in her KEDtalk a year ago about the mission.

“Exploration is a human imperative,” she said. “It’s built into us, everything from Magellan to Captain Janeway. Exploration aligns humankind looking outward, instead of allowing us to be distracted by the irritations that lie between us, both as people and as nations.”

We have seen planets made of rock, ice and gas. Psyche will voyage out between Mars and Jupiter, to a place that has never been visited, only glimpsed in photos as a pinpoint of light.

“We have never seen a metal planet,” Elkins-Tanton said. “We do not know what this will look like. ... So this would be true exploration and true discovery.”

The Lucy mission, meanwhile, will voyage to six primitive asteroids, measuring the surface temperatures on each with an ASU-designed and -developed thermal emission spectrometer, said Philip Christensen of the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

"With each new mission, we're expanding the types of solar system objects we're studying here at ASU,” said Christensen, who is the instrument's principal investigator and designer.

Jim Bell teaches a class called “Exploration: The Human Imperative.” The planetary scientist is also deputy principal investigator on the Psyche mission. Bell said there’s no simple answer to why humans explore.

Sometimes it’s pragmatic. All the local resources have been exhausted and it’s time to move to another place, so a scout is sent out. Sometimes it’s for glory, to expand an empire like Alexander and conquer foreign lands. Sometimes it’s economic, searching for gold or timber or whales.

“Now we’re more in an era where it’s fulfilling our curiosity,” Bell said. “It’s understanding our planet’s and our species’ place in our solar system and galaxy. ... It’s become this mix of knowledge and thrill and inspiration that kind of drives explorers.”

"Every time we send a mission into space, we get surprises."

— Lindy Elkins-Tanton, director of ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration

Explorers are simply born that way, Bell said.

“In my experience that’s not trained,” he said. “People are born with it. A baby wants to get out of the crib. A kid wants to explore a cave. It’s built-in. ... It must be a good thing; otherwise, natural selection would have bred it out of us.”

Today’s explorers on the true cutting edge of discovery are sitting in air-conditioned offices and aren’t likely to worry about starvation, even if the vending machine goes empty. That doesn’t make them fundamentally any different from Lewis and Clark, Bell said.

“It’s a different modality,” Bell said. “We’re using different tools. We’re not using our bodies. ... In space science, 99.99 percent of us can’t go there, so we use these machines, telescopes, satellites, landers, rovers, orbiters — these machines are projections of our senses. It is different. None of us are in physical danger — maybe in danger of losing our jobs if our mission don’t get selected. But we’re not in physical danger, other than the distress of watching our rocket blow up. ... But it’s still a way of exploring and reaching out to new destinations and discovering them.”

Right now, humans are earthbound. That’s changing. We’re not going to be stuck here forever.

“At some point, in the far future it will be possible to go to these places,” Bell said. “Those people will be putting their lives on the line. ... There’s purpose to it. It’s an evolution. Galileo was an explorer. His tool of exploration was a telescope. There’s a continuity of explorers and reasons to explore. Those of us doing modern space science are explorers.”

And, being explorers, they are continually rewarded.

“Every time we send a mission into space, we get surprises,” Elkins-Tanton said. “The solar system surprises us and gives us things we don’t anticipate every time we send a mission out there.”

ASU has an official University Explorer. Scott Parazynski is an astronaut, doctor, mountaineer, pilot and polar explorer. We reached out to him, but he wasn’t available for comment.

He could be in space, for all we know.

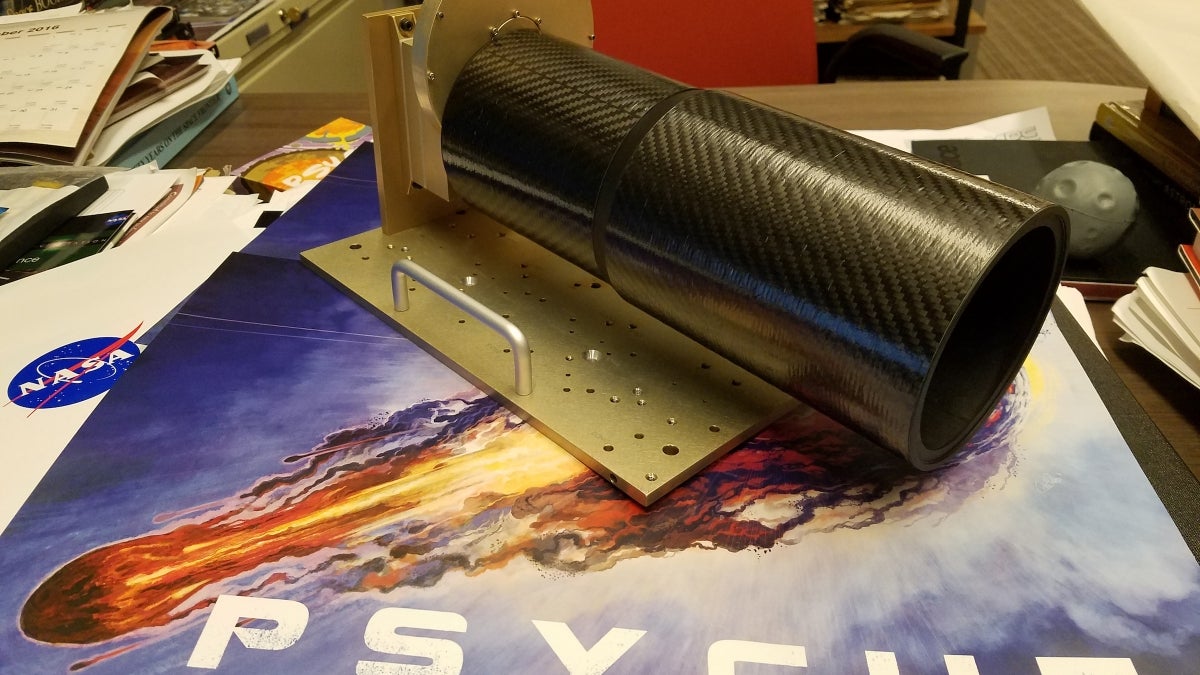

Top image: The Psyche mission will examine a metal asteroid, using devices that include a multispectral imager. Image courtesy of NASA Discovery Program

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…